In the pantheon of history’s strongest, most powerful women, high up in the ranks alongside Cleopatra and Queen Elizabeth I sits Empress Catherine II, commonly referred to as, fittingly and simply, Catherine the Great.

The most influential woman of the 18th century, she enjoyed a 34-year reign that stands as the longest of any woman in Russian history, during which time her ambition and industriousness afforded her the remarkable distinction of turning her adopted home country into a global superpower. But she was also considered a hypocrite, a warmonger, and a woman possessing an excessive sexual appetite for the time.

Catherine became empress of Russia at 33 years old despite possessing zero Russian blood and having no claim to the throne. Rather than political power being bestowed upon her, Catherine seized it.

The empress was a consummate intellectual, voracious reader, and prolific letter-writer who corresponded with prominent thinkers of the era, such as Voltaire, the Baron von Grimm, and Diderot. She adored the arts—her collection comprised the foundation of the Hermitage Museum—and authored countless articles, operas, plays, and even fairy tales.

If mimicry is flattery, then Empress Catherine is among the most adored of all time. Many starlets have portrayed Catherine the Great in plays, film, and miniseries. Her legacy also inspired much music, books, and numerous paintings.

The empress captures our attention the most for her brazen sexuality. If we think of libertinism in the 18th century, we usually think of men. But Catherine was wildly liberated for the time—and on the throne of Russia, of all places. For much of history, her accomplishments were overshadowed by her lasciviousness, which was regularly and unfairly mischaracterized or misunderstood. But the empress was much more than her sexual exploits. Here we are reminded of her dizzying ascent to power; her unapologetic decisiveness and strength; and her steadfastness as she navigated a world she occupied centuries before her time.

While much of the empress’ life is well-documented, there is still much unknown about her personal life and countless urban legends and myths about her motivations.

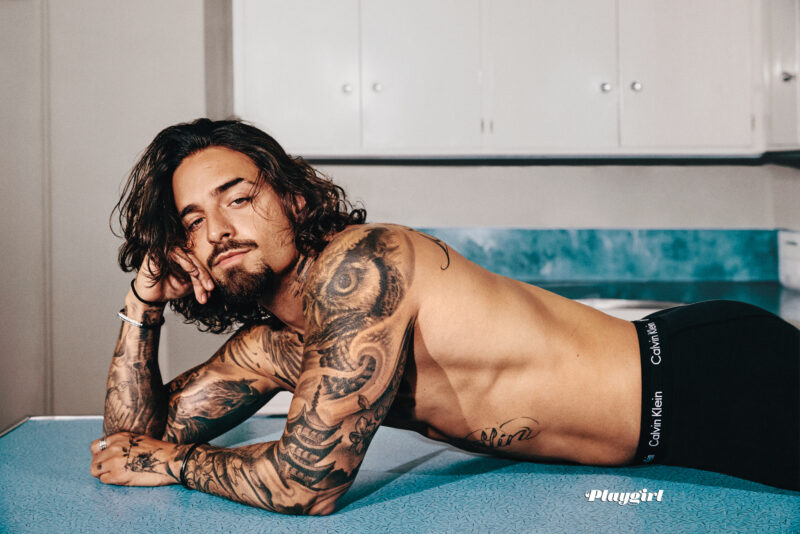

‘The Great’ • Courtesy Hulu.

Early Life

Catherine was born in 1729 as Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg in Stettin (present-day Szczecin in Poland). Her father was a minor prince working as a general and governor, and her mother was related to the dukes of Holstein. Despite the family’s royal ties, they lived in poverty. Catherine’s mother was determined to use familial connections to achieve upward mobility, and groomed her daughter from a young age to marry into wealth and power. Catherine was a tomboy and highly educated, reading philosophical literature as a young teenager.

At 14, her mother secured an invitation for Catherine to the Russian court of Empress Elizabeth, ruler at that time. Catherine so charmed Elizabeth that the empress received her into the Russian Orthodox Church—resulting in her new name, Ekaterina Alexeievna (Catherine)—and arranged for a marriage between Catherine and Grand Duke Charles Peter Ulrich of Holstein-Gottorp, Elizabeth’s nephew and heir to the Russian throne. Peter’s grandfather, Peter the Great, had ruled Russia from 1682-1725.

Elle Fanning and Nicholas Hoult in ‘The Great’ • Photo: Hulu.

Marriage and Ascent to Throne

Catherine enthusiastically shed her Germanic background to embrace her new, Russian life, becoming proficient in the language and customs. Her husband behaved conversely; Peter begrudged Russian ways of life and openly admired Empress Elizabeth’s adversary, Frederick II of Prussia. As Catherine read literature, Peter played with military figurines. Where she was stoic and steadfast, he was poorly mannered and immature.

The relationship was a clear mismatch, but the two nevertheless embarked on an 18-year marriage in 1745 when Catherine was 16 and Peter 17. It’s well-documented that the marriage was unconsummated for at least eight years, each partner preferring lovers to each other. Later in life, Catherine claimed her son, Paul, was the result of an affair arranged by Empress Elizabeth between Catherine and Sergei Saltykov in order to produce an heir. Historians still debate the validity of such claims. She had two more children, Anna (who died at just 14 months old) and Alexei, with paternity lines doubted for each.

When Elizabeth died in 1762, Peter ascended to the throne as Emperor Peter III with Catherine as empress consort. Peter was exceedingly unpopular in Russia. Catherine, too, was losing patience with Peter as it became clear to her he planned to make his mistress his wife. If that came to pass, Catherine was likely to be sent to a monastery—a common occurrence for divorced royal spouses at the time.

“Had it been my fate to have a husband whom I could love, I would never have changed towards him,” Catherine wrote later in her life. As Peter increasingly alienated the courts and his wife, the 33-year-old Catherine saw an opening and started plotting a coup with military officer Grigory Orlov, with whom she was having an affair.

Orlov led the coup with full support of Russia’s military and noble factions, including the Orthodox church. Peter was arrested, forced to surrender the throne just six months into his leadership, and exiled to Ropsha, a village outside St. Petersburg. Catherine was declared empress.

Eight days later, Peter was killed. It’s still unclear whether Catherine ordered the killing, agreed to it, or if the murder was carried out without her knowledge. No one was held accountable, although many believed Orlov’s brother, Alexei, carried out the hit.

Marlene Dietrich in ‘The Scarlet Empress’ • Photo: Paramount Pictures.

Atop the Throne

Catherine’s rule began with social and political reforms. Her most notable contributions to Russia were growing its borders, westernizing the country (a continuation of Peter the Great’s efforts), and a cultural and scientific renaissance. Literacy exploded during Catherine’s reign, as did the establishment of a press. She oversaw the spreading popularity of theater and opened Russia’s first state-funded school for women, while also outlining the rights of nobles and city dwellers in her charters. Russia welcomed large-scale immigration from throughout Europe during this time, and earned the distinction of being a great power.

But Catherine was also prone to absolutism—the belief that she, and she alone, could rule—which prevented her from collaborating on the actual running and management of a huge country. And despite her outspoken disapproval of serfdom, feeling it functioned much like slavery, she did not outlaw or even change it during her rule. Her inaction exacerbated unrest between peasants and their lords—a growing civil war that metastasized as a massive peasant rebellion in the 1770s which threatened to derail the Russian Empire.

Catherine’s time atop the throne was punctuated by her lovers—as many as 22 during her rule—some of whom, like Grigory Potemkin, were promoted to high office. Her sexual independence and string of relationships continued for the duration of her life. Those whom she elevated into positions of power helped fortify her support among peers and only strengthened her position. Others she enjoyed strictly for pleasure.

Catherine had “two passions, which never left her but with her last breath,” wrote Charles François Philibert Masson in his memoirs; “the love of man, which degenerated into licentiousness, and the love of glory, which sank into vanity.”

Helen Mirren in ‘Catherine the Great’ • Photo: HBO .

With few details known of her exploits at the time, rumors abounded—and many were spread by her male rivals. She was characterized as a nymphomaniac; was said to collect erotic furniture featuring carvings or parts depicting various parts of the human anatomy; and there was even gossip that she died while engaged in a sexual act with a horse. The smear campaigns were relentless and continue to present-day.

While much is left to conjecture, we do know the empress leveraged sex to get what she wanted politically and to expand her power. Marrying again would have diminished that light, she realized, so instead she instigated relations with noble favorites who could expand her dominion. From Polish nobleman Stanisław Poniatowski (rumored to be the biological father of her daughter Anna) to Orlov, who facilitated the coup, to Russian aristocrat Alexander Vasilchikov, Catherine’s partners benefited from her standing as much as she from theirs.

Her relationship with Potemkin was the most intense, well-known, and enduring. Even after their physical partnership waned, evidence suggests he helped select and groom partners for Catherine.

Her legacy stretches to present-day. Depictions of the great empress can be found across virtually every art medium and in many countries. Notable screen representations include Marlene Dietrich in the 1934 drama The Scarlet Empress; Julia Ormond in the 1991 miniseries Young Catherine; Catherine Zeta-Jones in the 1995 TV movie Catherine the Great; the eponymous Helen Mirren in the 2019 HBO limited series Catherine the Great; and Elle Fanning in the 2020 dark comedy Hulu series The Great.

Despite the many misconceptions about the empress and her complicated life and rule, Catherine the Great was inarguably ahead of her time in terms of ambition, sexual autonomy, and unapologetic intellect and curiosity. Her power and position flipped gender norms of the day and ripped an opening in our cultural fabric through which feminist thought could flow with increasing regularity.

*Quote from the HBO limited series Catherine the Great