Marking an unprecedented milestone in reproductive freedom, Opill—the first over-the-counter oral contraceptive—hit the market in March 2024.

The Pill stands as an unmatched symbol of sexual liberation and has since 1960 when the Food and Drug Administration first approved an oral contraceptive for women. Opill contains the hormone norgestol, which was approved in 1973 by the Food and Drug Administration for prescription contraceptive use.

The circuitous story of American contraception is fraught with medical misinformation, risky quackery, and dangerous—and often illegal—work by advocates for bodily sovereignty for all. In exploring that history, and talking with experts working on the front lines of sexual autonomy, a stark picture comes into focus of the long road it took to reach such a momentous landmark in American history.

“When used correctly, [the pill] allows people to make decisions from a perspective that centers their autonomy for the most part,” sex worker and therapist Raquel Savage told Playgirl. “[The idea that] sex equals creating children is a very archaic understanding of sex, sensuality, sexuality, intimacy, and reproduction. And it’s not that, doesn’t need to be that, nor has it ever been. Humans have always been navigating ways to prevent and terminate pregnancies. I get to make the decision of whether or not I’d like to conceive a child, whether or not I would like to terminate a pregnancy. Those are my decisions and have nothing to do with whether I want to engage in sex of any kind, including penetrative sex.”

Playgirl • May 2024.

In 2019, around 35 of every 1,000 pregnancies were unintended, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The well-documented link between unplanned or unwanted pregnancies and adverse outcomes for children and birthing parents means the expansion of birth-control access takes on new import in a post-Roe v. Wade landscape.

Since the Dobbs decision, contraceptive and abortion access in the U.S. has been increasingly precarious in some states while others have taken steps to protect access. Many communities across the U.S. are situated in “contraceptive deserts” without health centers offering comprehensive options for contraception.

“If we’re worried about pregnancy risk, we end up in a state of fight or flight almost constantly,” Gigi Engle, a certified sex and relationship psychotherapist and sex expert at the LGBTQIA+ dating app, Taimi, told Playgirl. “Being able to have sex freely, without the consequence of pregnancy, makes having sexual autonomy and pleasure possible. I don’t think I can overstate how much of a positive impact having access to safe, reliable birth control can have on someone’s life.”

The success rate—and story—of birth control is complicated and varied.

The success rate of birth control varies greatly depending on the method. Calendar-tracking and spermicides—two of the oldest forms of birth control—rank lowest; followed by condoms, cervical caps, and sponges; then injections, pills, patches, vaginal rings, and diaphragms. Implants, IUDs, and sterilization are considered the most effective forms of birth control.

“Technology around preventing pregnancy has been around a long long time,” Savage told Playgirl. “It has been an important part of bodily autonomy for any person (…) to be able to make the decision around whether or not they want to have a kid.”

Photo: Courtesy of Raquel Savage.

The birth-control timeline goes back to at least the fourth-century B.C. when Greek philosopher Aristotle became among the first to advise the use of spermicides inserted into the vagina to prevent sperm from reaching the uterus. The spermicides Aristotle promoted were derived from expensive oils, such as cedar oil or frankincense, or tinctures like lead ointment. The price tags on the products created a familiar problem of a financial barrier for those who would be most negatively affected by an unwanted pregnancy (to say nothing of the potential health side effects).

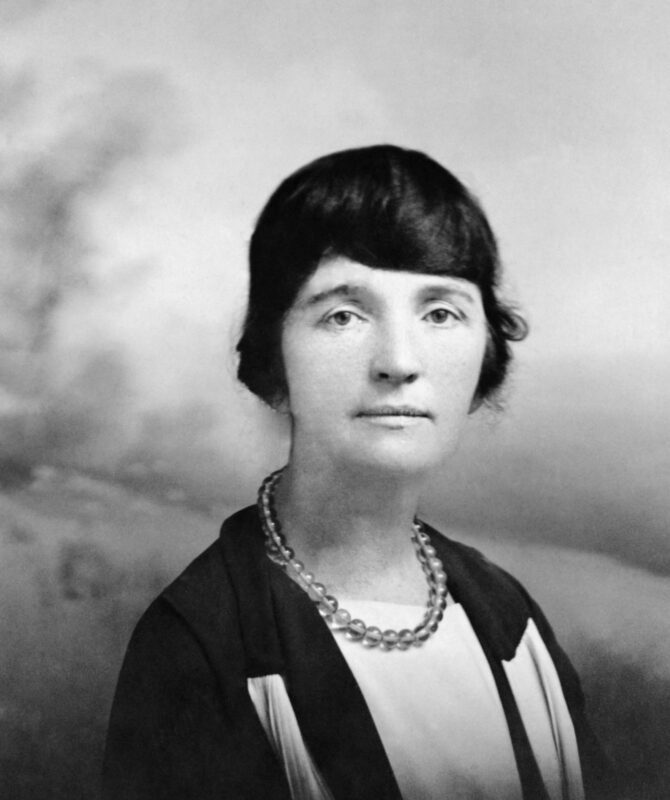

Fast-forward a couple of thousand years to 1912, when a young nurse named Margaret Sanger worked on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. At that time, birth control was a largely illegal or prohibitively expensive process. Condoms and diaphragms were high-priced, difficult to get a hold of, and often required an exam by a doctor. Other products on the market—from cervical caps to douching syringes—were middling in their efficacy and similarly difficult to find. Sanger found herself imagining a magical sort of contraceptive pill that could be taken as simply as aspirin.

In 1914, Sanger published the first issue of her feminist journal, The Woman Rebel, in which she expounded on the importance of women’s sexual autonomy and advocated for instances when one ought to avoid pregnancy; namely during illness or poverty. It was in an issue of The Woman Rebel that Sanger coined the term “birth control.” Sanger also began distributing contraceptives; she was indicted in 1915 for sending diaphragms through the mail.

In 1916, Sanger opened the country’s first birth control clinic in Brownsville, Brooklyn. With contraception and abortion illegal in the U.S. at the time, Sanger and her clinic staff provided information to individuals curious about various birth-control methods and options for handling unwanted pregnancies. The circulation of such information was considered obscene and illegal according to the federal Comstock Act, but people sought Sanger’s clinic out regardless. The clinic was shut down after just 10 days for being in violation of the Comstock Act but laid the groundwork for the eventual founding of Planned Parenthood Federation of America—not to mention a 1918 legal ruling that birth control could be used for therapeutic purposes.

Margaret Sanger • Photo: Everett Collection Inc/Alamy.

Women gained the right to vote in the U.S. in 1920. The victory swelled support for women’s rights and ushered in a decade of massive progress for women’s sexual autonomy. Within a few years Sanger had formed the American Birth Control League, the first legal birth control clinic in the U.S., and the Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau in Manhattan. The Birth Control League and Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau merged in 1942 to form the Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

During the Great Depression, an unintended pregnancy could spell calamity for many Americans. Companies eager to tap into that national anxiety found loopholes for selling contraceptives, which were still largely illegal. Terms like “feminine hygiene” were used to market popular suppositories, vaginal jellies and foaming tablets. Other products—like antiseptic douches—were downright dangerous if not sufficiently diluted before use.

Among the most popular brands of douche at the time was Lysol, which prior to 1953, contained creole—a compound shown to cause burns, inflammation, and—in extreme cases—death. Despite this, douches became the most widely used form of birth control from 1940-1960 as they were inexpensive, available without a doctor’s consent, and commonly made at home. They were also wildly ineffective.

Contraceptive use exploded in the 1950s, with Americans shelling out around $200 million a year on the prevention of pregnancies. With improved condom designs and better education on the shortcomings and potential dangers of douche solutions, “rubbers” caught up to douches in popularity and quickly became the most ubiquitous American birth control method. Despite such obvious public support, pharmaceutical companies and medical institutions took no moves to conduct contraceptive research. Critical funding in the 1950s for the clinical development of the birth control pill instead came from Katharine Dexter McCormick, one of the first women graduates of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and beneficiary of her late husband’s International Harvester fortune.

McCormick contacted her longtime friend and fellow rabble-rouser Margaret Sanger to inquire about where her financial contributions could make the most impact. Sanger shared her vision for a female-controlled, oral contraceptive; the rest is history. McCormick wrote her first check to develop the Pill in 1953, in the amount of $40,000. Throughout the Pill’s development until its approval in 1960, she donated more than $2 million (more than $20 million today).

By 1962, 1.2 million American women were on the pill. By 1965, Congress passed a federal law stating married couples had the right to use contraceptives without government restriction. Since then, more than 300 million people worldwide have used the pill as a safe and effective means of birth control.

The fight is far from over.

Requiring a prescription to access the pill until now has remained a barrier to entry for many, underscoring the value of Opill.

“Having to see a doctor or medical professional to get a prescription is a form of unnecessary gatekeeping that has seen so many young women (…) having to forgo birth control,” Engle said. “Because of the predatory nature of the American health care system, many people don’t have access to affordable health care, making visits to the doctor impossible and extortionate. Making it easier for young women (…) to get access to birth control means that they will be able to go and get birth control without having to jump through hoops, making it a lot more likely that they’ll take it—and take it consistently.”

Gigi Engle • Photo: Dolsmedia @dolsmedia

“I don’t think there is really anything else that has had a bigger impact on women’s sexual autonomy than birth control,” Engle said. “Being in control of our reproduction gave us access to the workforce and to our own livelihoods and futures like never before. Suddenly, we were in the driver’s seat of our own lives, free to plan for the futures we actually wanted.”

Today, Opill costs $19.99 for a one-month supply or $47.97 for three months. It’s available for purchase in major grocery stores, pharmacies, and online at Opill.com. While that renders birth control in some ways more accessible than ever, the cost also creates a barrier to entry we can’t ignore—and forces us as a society to continue pushing the envelope in the fight for accessible birth control for all.