Last month, I sat down with Reem Morsi, director of Banned and Valerie Buhagiar and James Milligan, director and producer of The Dogs respectively, to speak about their work and experiences as independent filmmakers. Both films, which screened at the Female Eye Film Festival, expertly interweave techniques of genre filmmaking with humanist storytelling to explore our closest-held anxieties, both real and otherworldly.

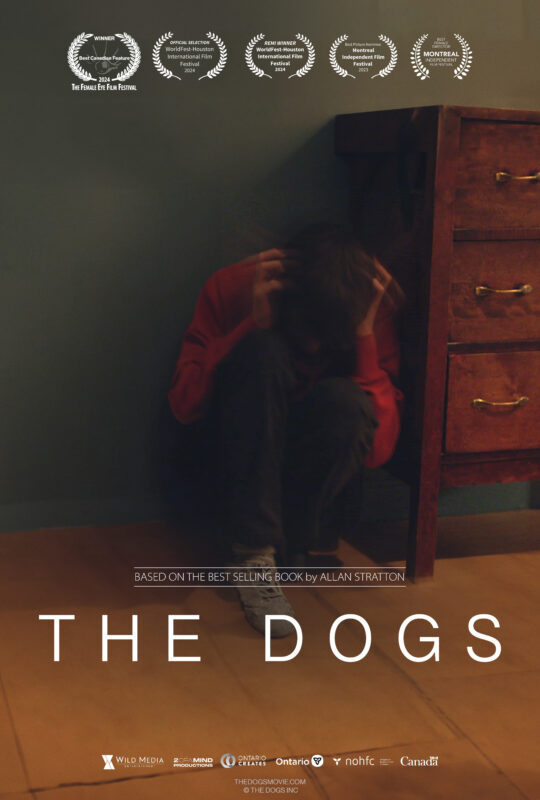

The Dogs, named Best Canadian Feature at the FEFF, follows the story of 13-year-old Cameron and his mother, who flee an abusive situation to find solace in a small town. Yet the echoes of generational trauma continue to reverberate around Cameron when he begins to see apparitions of a boy from the 1960s and learn the tragic history of his new home. Director Valerie Buhagiar and producer James Milligan told me about their process.

What is The Dogs about to you?

Valerie: There’s the surface plot, of course: a boy and a mom run away from a vicious dad and find comfort in a small town where the horror meets them again. That’s the surface, but really, it’s “what is the horror”? The horror being the dogs, and the dogs also being the men—the fathers in this film, who are parallel to the dogs in that vicious attack.

James: It’s based on the book by Allan Stratton. As with any book, there’s always more there than you can put on the screen. We knew we had some horror elements to our film, but we didn’t want to make an exclusive horror film, per se. It’s a story about family and father figures. There’s this parallel between incidents that happened in the past in this house that are coming through our ghost character. There’s a connection between those two worlds and a mystery that ensues. We had a few different elements: we had a mystery, we had some really fearful moments, we had the dogs, which are more of a metaphor than anything else. We wanted to add some more nuance and depth to the story, rather than making a straight-ahead genre film, and we were able to do that thanks to the book.

‘The Dogs’

I was interested in genre—I think a lot of the time, in horror, the scary thing is representative either of a moral panic or a very concrete and real human issue, like we see in The Dogs with family domestic abuse. But the ghost in this case was actually a source of comfort.

Valerie: I’ve seen ghosts all my life. This is one of many reasons I was drawn to this story. I brought that with me when we made The Dogs, knowing that initially, when you see ghosts, you go like this [stiffens] and then, depending on that entity, you may feel comfort from it. I was told that people see ghosts when they’re grieving, and that doesn’t just mean a loss of being. A loss of a relationship or just feeling lost—when you’re in those places in your life, you open up. When you’re vulnerable, they appear.

James: The film really tracks Cameron’s descent into madness, to sum it up in a phrase. It starts with the move and the upheaval of his life, and then we introduce this paranormal element. At first, it’s terrifying, until we realize it’s a benign character that he attaches himself to, but nobody else sees him. So, is he losing his mind? Is he not? And we as the audience don’t know if this paranormal entity is really there, or if it’s a figment of his imagination.

Did you already have a vision going into the filmmaking process?

Immediately I was thinking of Andrew Wyeth paintings for the present day and Norman Rockwell for the past, with a dirty filter on it. I tend to come up with a lot of ideas, almost too much. But the good thing about that is you can weed through it together. It’s collaboration, all around. It takes a community to make a film.

Valerie Buhagiar • Photo Mark Cassar.

Having been in the film industry for several years—as a woman, and in general as an independent director—how have you seen it change? Do you think it’s easier or harder?

There is now more space for female directors than there used to be, but we still have a long way to go. I am grateful to the women who came before me and opened doors, and I am thankful to the younger generation for demanding better and more stories about women, created by women.

Valerie, you started as an actress. How did you make that transition from acting to being behind the camera? And is there anything that you learned from being on set that informed your directing?

Yeah, they do say the best directors are actors and editors, because we’re storytellers. I know actors, and I know how to make them feel safe. And that’s the key, just to make them feel safe so that they can go the distance. As soon as we had our cast, I sent every single cast member a backstory. Even the waitress with one line had a backstory. And I asked them to continue the backstory with certain questions. All of the other characters, the ones that aren’t on screen as much, came to me and said, “I’m so glad you’re so inclusive.” It’s wonderful, because I truly feel like that tone vibrates throughout the film. And then I also asked them all to pick a tune that represents their character.

There was one really difficult scene, where the lead has to blow up. His mom, a really wonderful, supportive person, came to me privately and said, “He’s really nervous about this scene.” So I pulled him aside and we went for a long walk. He had to break down and cry, and even veteran actors find that hard. It’s not about showing us tears, it’s about reaching the other person. We were supposed to do three scenes that day, but I said, “We’re just going to do this one. Find a way to squeeze those other ones elsewhere. The actor needs time.” So, we took the time, and it turned out to be a fantastic scene.

That is the key to everything, making people feel safe so that they can be their authentic self. And that’s what we want to see, right? Even though it’s a genre film, we want to see authenticity, because the audience wants to believe it. We believe that this boy is seeing this ghost and we will feel it with him. That’s what I learned as well: if I’m feeling something in the moment, we will feel it later. You do your best to feel as much as possible on set.

Banned, directed by Egyptian-Canadian filmmaker Reem Morsi, is a multi-genre triptych set in an unnamed country in the near future, in which totalitarian Islamophobia is on the rise. The film follows disparate members of an extended Muslim family fighting to survive in an increasingly hostile environment.

‘Banned’

Tell me about the film in your own words. What is it about?

The film is actually a very long, arduous journey. It started out with the attacks against Muslims in North Carolina. I wanted to make a film about it. So, I wrote a script, but I decided to shelf it, to try a new approach to the issues so people would want to watch it. Because when you say a film is about Islamophobia, not many people are going to want to see that.

So, from that, I made the feature in 2019. And it was about a family who wake up, and there’s an attack on them in their home, and they try to escape. It’s a dystopian, imaginary world in the future. It was very, very low budget. It was my first feature; there were loads of issues. I was very passionate about the topic, so it was exactly what I wanted to say, it was very expositional and on the nose. And because of the low budget, we had lots of technical issues. I looked at the film and said, “I can’t release this.”

Finally, after years of not knowing where to go with the story and how to make it something that I would enjoy, I said, “This is my first feature and an opportunity to experiment and defy expectations.” I decided I would shrink what we shot in 2019 into one little story, as if it’s a short. That’s the story that was in the middle, and I created two other stories, one in the beginning, one at the end. The first story is magical realism and comedy, and the last story is more like a psychological thriller. I’ve never seen a film about Islamophobia that is multi-genre and with a fantastical element to it.

How has your experience been in the film industry so far? Specifically as a woman of color, do you feel like there are any unique challenges?

Well, you would be surprised that my biggest challenge is my accent. I’ve heard that said to me before, when I am in an interview and they hear my accent, they feel like, “We can’t hire her; she’s not Canadian enough.” That has been really disappointing. So it has been a bit of an issue, being an immigrant, more than anything. I moved here a few years ago, but I’m very Egyptian.

And at the very beginning, being a woman and of color was an issue, but actually with all the attempts to push BIPOC creators into the light, it has been helpful in ways, to get some grants and some financing. When it comes to TV, I think that the balance is not there yet. I think it’s really a closed club. So, I feel that as a new person in the TV industry, and being a woman and BIPOC, I don’t know how much of that is a factor or if it’s the fact that I’m new and haven’t done enough TV. That’s why I started creating my own shows, and I’m developing many of them. I can get access to training, funding, shadowing opportunities; I’ve been very lucky. But to actually be hired on a TV show, that has been a huge, huge challenge. I haven’t succeeded in doing that… yet.

Reem Morsi • Photo courtesy Reem Morsi.

You previously worked in human rights at the UN, right? Do you feel like your filmmaking is a progression of that work?

Absolutely. I always wanted to be a filmmaker since I was a kid, but then I put it aside. “It’s impossible. You can’t get there. It won’t happen.” But when I went into human rights, the very striking stories that I saw, I realized I was starting to write everywhere. I’d have napkins I’d be writing on; I’d be writing on my hands, because these stories were so incredible. I was in Sudan, I was in Palestine, I was in Kosovo, I was all over in various countries and having to see how different people live in these situations, and at the same time, how the spirit of survival takes over. There would be romance and falling in love, despite the bombings. It’s just incredible, the human spirit and the will to survive and live. I worked one last UN mission, and I actually started applying to film school at the end of that mission.

I feel like in my work in general, there’s always an element of human rights. My ideal is to make genre films that reflect human rights issues and threats. I really love using a lot of symbolism and trying to talk about an issue using genre. That’s the kind of work I want to be creating more of. It seems very simple on the surface but actually has all these layers of symbolism about race, or gender, or social justice. If you use vampires or zombies to represent oppression, I’m really drawn to that. It gives you room to take it on the surface or read between the lines.

What are you hoping people will receive from this film?

I’m just hoping that maybe people who wouldn’t usually watch a movie about Islamophobia would be intrigued by the genre or by what they hear and find it interesting enough to watch, and maybe they’ll have a change in mentality. Having lived in many Western countries, Muslims are always seen as a closed box. When we have more films showing the domestic life of Muslims, the problems, the things that make them happy, it normalizes Muslims and Islam. That would be my target.