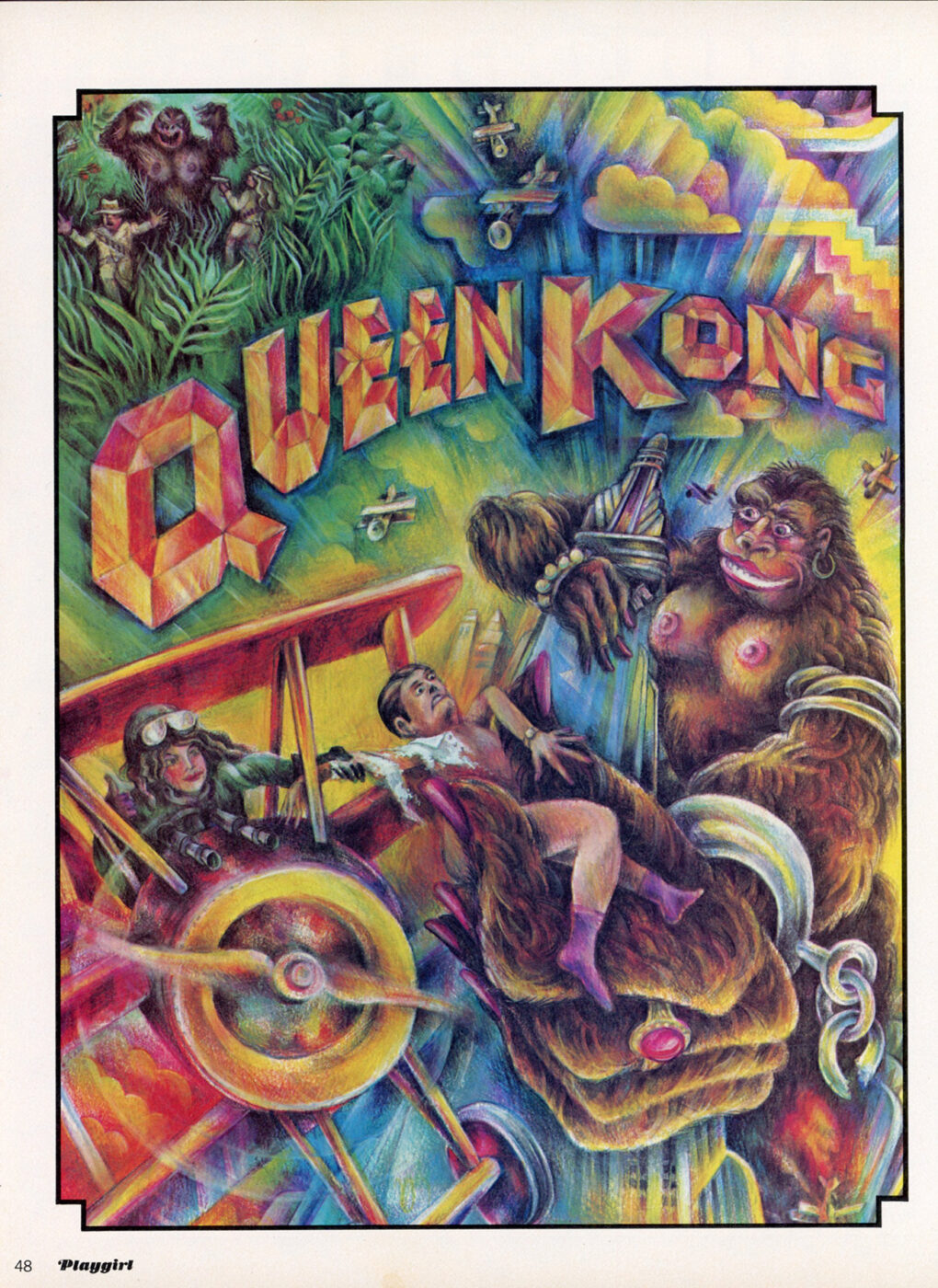

Excerpt from Playgirl, August 1973

There must be better places to observe a love scene from than somewhere over the hero’s shoulder—for female filmgoers, at any rate. However, the interests and desires of women have seldom been taken much into account—in Hollywood or anywhere else.

In the days when they used to make “women’s pictures”—a form conspicuous by its absence ever since the last Lana Turner version of Madame X several years ago—there was a lot of talk around the studios about Love as the great feminine subject. But love was then regarded, in the cinema anyway, as something altogether apart from sex.

Love was emotion generally felt in a rather abstracted sort of way, but always, of course, in considerable comfort with gowns by Edith Head or Helen Rose, and furs and jewels both getting bigger billing than the writer or director. Love was soft focus and yearning, a gentle embrace with every hair in place, and sex was something quite different. I mean, could you imagine Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson ever actually going to bed together?

The reason for all this was plain enough: that was the way women liked it. Who said so? Why, the men who made the movies, of course. Not that they were exactly shrinking virgins themselves, but it is remarkable how long positively Victorian ways of thinking about female sexuality persisted. Men who had very sophisticated ideas about sex, from their own point of view, were quite likely to fall back on old assumptions that women did not feel any positive interest in sex at all, though they might on occasion be persuaded to submit to a man’s animal desires. This was no doubt flattering to their masculinity, whereas the challenge offered by any woman who might make the first move, pick and choose her lovers, and be ready to dismiss anyone who didn’t come up to standard with “I’ve seen better,” was too much to cope with. Significantly, any woman in movies who did not take a completely passive attitude to sex was instantly characterized as a tramp.

To an extent, there was an excuse for this in the shape of the Hays Code. It seems extraordinary now to think of the years that Hollywood producers went in terror of this production code with its ridiculous requirements, giving, as it did, several generations of Americans very strange ideas about the relations of the sexes. Married couples, for instance, always slept in separate beds, and as often as not in separate rooms. Think of the number of movies in which a wife repulsed a husband’s suggestion that he might come to her room with, “But what would the servants think?” If by some mischance they did end up on— not of course in—the same bed, one of them would naturally keep at least one foot on the ground all the time.

But though the Hays Code did help to perpetuate the double standard — guilty men might be forgiven, but guilty women always had to Pay The Price — it soon turned out that producers’ disregard for women’s sexual interests lay deeper than mere conformity to some arbitrary outside rule. It was a matter of habit, a habit that women were not, for the time being, vocal enough to query seriously.

Of course, things have changed in this new era of sexual freedom and permissiveness we hear so much about. Or have they? What about the most talked about sexual film of recent times, the one film that just about everyone who insists he or she would never normally go to “one of those films” feels impelled to go to?

Last Tango in Paris is admittedly a perfect example of the porno film for the man who wouldn’t be seen dead at a porno film. Most of the sex is on the soundtrack with a liberal use of four-letter words, or handled in the old- fashioned way by implication. It is only what is implied in exactly how and where that notorious pat of butter is used as a lubricant that the film goes appreciably farther than its more outspoken predecessors. And that, for most of its audience, is quite far enough. If the last time you went to the movies was to Airport or Love Story, Last Tango in Paris probably would seem pretty hot stuff. To anyone used to the sort of thing a lot of European film-makers have been offering of late, or to the Andy Warhol films, so widely shown these days as to hardly count as underground any more, it will probably seem fairly mild.

If Last Tango is supposed to push the frontiers a little farther out than ever before, it is worth looking a bit more closely at what the female half of the audience might expect to get out of it. The film, as just about everybody must know by now, is the story of a purely physical sexual relationship. Two people, a middle-aged American domiciled in Paris whose wife has just killed herself (Marlon Brando), and a respectably engaged young Frenchwoman (Maria Schneider), meet in an apartment each is thinking of renting, and right away, there in the bare unfurnished room, he rips her panties off and makes obviously very satisfactory, brutal love to her. She apparently feels a sentimental, “feminine” desire to get to know him better, to find put more about him, but he refuses: this has to be straight sex, animal-to-animal, and that is all there is to it. Much of the film thereafter (though not so much as excitable commentators might lead one to believe) consists of their meetings in the apartment for purposes of sex.

And that is where the unequal distribution of audience interest comes in. One way and another, we see a lot of Maria Schneider —just about all there is to be seen, in fact. When she gets her panties torn, they are very palpably tom; when she is meant to be naked she is unarguably naked, and any men in the audience can feast their fill on the sight of her breasts and pubic hair.

But fair’s fair. What corresponding thrills can women hope to get from the presentation of Marlon Brando playing his sexiest role in years as an attractively gone- to-seed-forty-year-old with only one thing on his mind? The answer is, virtually none. There is, to be sure, one nude tableau of the two of them together, but it is one of those artistically interlaced arrangements with arms and legs so ingeniously disposed relative to the camera that Brando, prettily dappled with shadow, might as well be wearing a pair of old-fashioned, heavy-duty swim trunks for all one can tell to the contrary. Elsewhere, he never removes his trousers, and any woman hoping for a vicarious thrill from Maria Schneider’s near-rape will have to make the imaginative leap of accepting that it usually happens to her without the rapist even unzipping his fly.

Of course, it can reasonably be maintained that erotic quality in films does not necessarily have anything much to do with explicit nudity. I remember that when all the full frontal stuff first started in respectable films with I Am Curious –Yellow, the international film festivals were immediately deluged with full frontals and simulated sex. And with the law of diminishing returns working it all out, what had once been very exciting in itself for its novelty value soon came to seem routine and boring.

At which point, I saw a Swedish film called They Call Us Misfits, a sort of documentary picture of a couple of Swedish hippies during three months of drifting life — in the course of which one of them makes a girl in front of the camera—teasing, cajoling, nibbling at her and finally, after about five minutes of petting, going to it. None of this, as it happens, with any significant degree of nudity for either of them beyond a bare behind heaving. And yet, even before the film got to that point, the scene was intensely sexy to both men and women because what was coming off the screen was a genuine erotic tension rather than a set of carefully simulated gymnastics.

Which is all very well if we are talking about the higher reaches of art. But with most movies, let’s face it, we are doing nothing of the sort. The satisfactions people look for in films are rather more simple and basic: a good laugh, a good cry, a gripping story efficiently told, and, yes, certainly, a bit of sexual titillation from time to time. And looked at in this light, the movies have undoubtedly played a lot less than fair with the women who were for long regarded as the backbone of their audience.

Nobody, after all, thinks it extraordinary that men have nude calendars, enjoy salacious centerfolds, and go to see films for which the main selling-point is that you see more of Brigitte Bardot, Raquel Welch, or whoever the current strip-star may be, than ever before.

Why should not women do, and be expected to do, likewise? The first problem, clearly, is to achieve general acceptance of any such idea in a predominantly masculine world of film-making. That lesson learnt, there are still other difficulties. Though, heaven knows, physically narcissistic male film stars are not exactly unknown, there is still a bigger block when it comes to their stripping in front of the cameras than for female stars. Most male film stars have some sort of hang-up about whether merely exhibiting themselves, selling their looks and personalities, is really fit work for a man. Even when they have little pretense to being actors, the excuse that they are acting does help them out. But if this defense were removed, if they were simply there as a sex object for female customers to relish, they would really be in the throes of an identity crisis. A crisis, one might say, which is long overdue for men in modem society. But that is another story…

… continue reading on PLAYGIRL+