CLINT EASTWOOD IS LIKE A FOOTBALL team. And not just one of those touch-and-go franchises that make up the numbers in the NFL. No. Clint is among those solid teams you have to watch for every year, like the Steelers, the Raiders or the Cowboys. America’s team; America’s actor. These teams are known for physical commitment, experience, their lack of sentiment, their code of hardness. They may not win every time out: but if you want to win, you’ve got to reckon on how to beat them. That means getting hit and hurt, and beat on, and staying in bed on Monday wondering if the damage was done by the men yesterday or by Mack trucks.

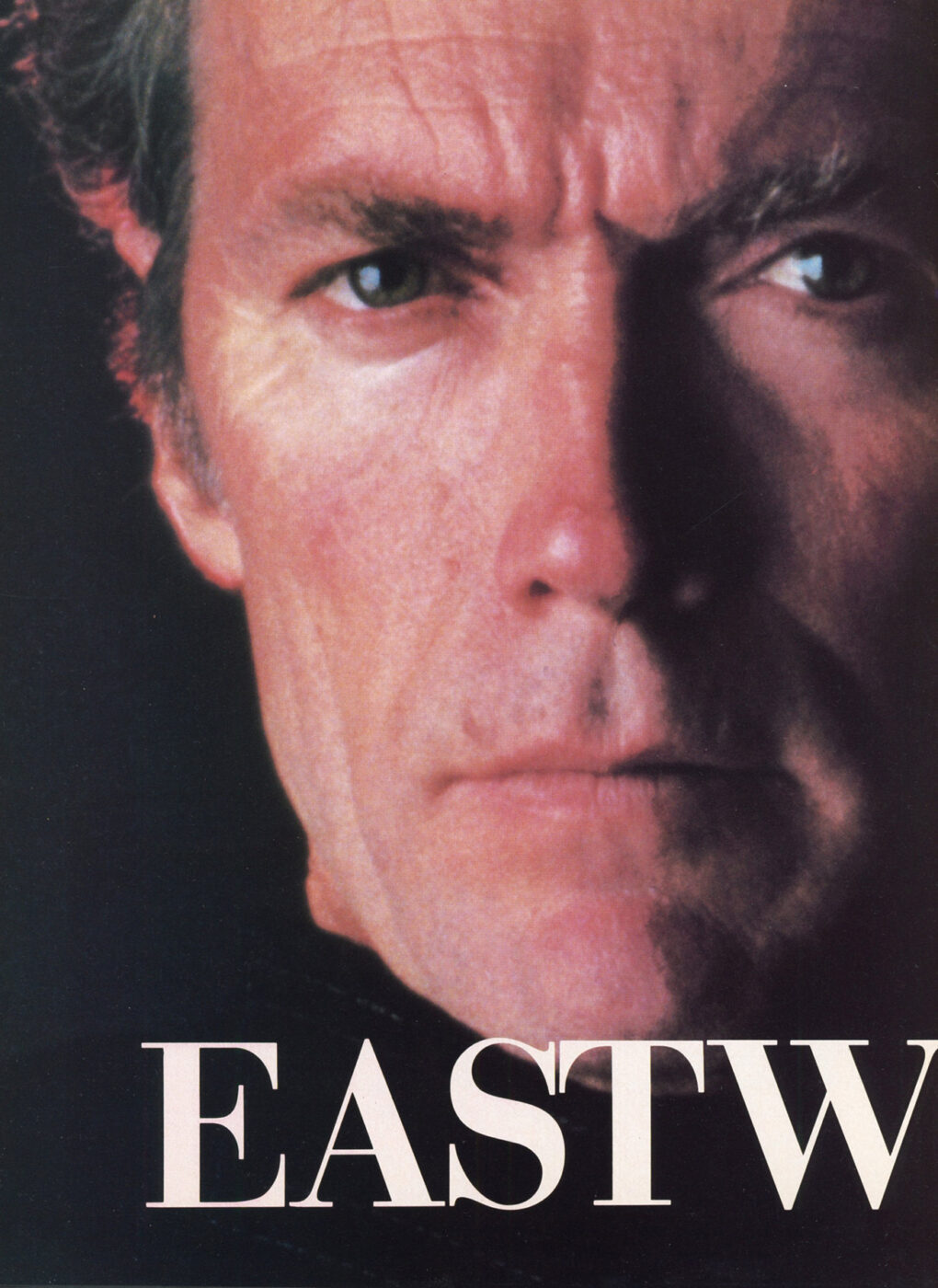

And Clint is all the team: He’s a lean, fast, six feet four inches tall wide receiver; he’s a cold, calculating quarterback with a cheroot peeping out through the bars on his helmet; he’s a linebacker destroying anyone who hopes to come through those holes; and he’s a strong safety, guarding the goal line. More than that, he’s the coach, patrolling the sideline, grim, planning and unmoved, no matter if he’s leading 37-3, or has just seen his team turn it over for the fifth time. Look at Clint, and look at Cowboys coach Tom Landry. All right, one is better looking than the other, but they have the same “I-dare-you-to-say-I’m-not-mean” face.

But Clint Eastwood is 53 this year, and truth to tell he does look more like Landry than he reminds you of Vince Ferragamo or A.J. Duhe. And just like America’s team, the Dallas Cowboys, America’s actor is beginning to creak and stumble. Three years in a row the Cowboys have been eliminated at the last test before the Super Bowl. And three years in a row, Clint Eastwood has bounced off the box office like it was a new defense and he was a worn-out bag of popcorn: Bronco Billy, Firefox and Honkytonk Man.

You have to wonder what Blue-Chip Eyes is thinking. As he wanders through the deserted clubhouse now, he can see the trophies of old glory: 1972 and 1973, number 1 box-office draw, the most profitable star in the business—that was based on Play Misty for Me, Dirty Harry, Joe Kidd, High Plains Drifter and Magnum Force. He was actor, producer and director—he was the man everyone wanted to see and cheer, and that made him very rich. But he didn’t get big-headed.

He was no flash in the pan. He averaged number 4 at the box office in the late sixties; he was number 2 in 1971 and 1974; number 6 in 1975; number 4 in 1976: number 3 in 1977; number 5 in 1978. Always there or thereabouts. Why: in the entire period of talking pictures, from 1930 on, only four people have done better—John Wayne, Gary Cooper, Bing Crosby, Clark Gable. And then, damn it, in 1979 and 1980, Clint did it again –number 1, with the most inventive Super Bowl play of all time. Third and 18 seconds to go. Eastwood takes the snap, drops back, looks, searches, then lets go the big bomb—60 yards through the air—and it’s caught, by an orangutan! Touchdown! A play to remember—Clint to Clyde!—Every Which Way But Loose, The Outlaw Josey Wales, Any Which Way You Can.

So, is this it, he must wonder? Should I get on with being middle-aged? Should I settle for being a director and a businessman, taking a few beers with friends and looking out at the Pacific? Can I really live without being up there on the screen and glaring at low-life scumbags as if I can see the worms in their skin? Have I reached the limit, or can I go for one more big one? Remember, John Wayne still had it for True Grit, and he was 62 then. Am I America’s actor, or am I not?

EASTWOOD HIGHLIGHTS

Highlight number 1: Magnum Force. Harry Callahan goes up against a wicked, clean bunch of cops who take the law into their own hands (which is just about what he did in Dirty Harry). He gets them one by one and at last it’s just him and Hal Holbrook, leader of the rogues. Holbrook has the drop on Clint. He’s in a car, he’s got a gun, and he tells Clint he’s going straight to the mayor to blame everything on him. Clint looks sour and strained, as if he’s trying to chew a nail and hiss at the same time. But he has primed an explosive device in Holbrook’s car. Now, don’t ask why Holbrook doesn’t kill him, or how Clint knows the bomb won’t wait to explode until Holbrook’s in a crowded area. You don’t ask questions in Eastwood pictures: they move too fast, and Clint just dares you to get out of line. Anyway, Holbrook drives off, and wallop—the big sack! Clint looks at the flames and the wreckage and he lets the words drag out like a dry leaf in a cold wind: “A man’s got to know his limitations.”

Highlight number 2: “A guy sits alone in a theater. He’s young and he’s scared. He doesn’t know what he’s going to do with his life. He wishes he could be self-sufficient, like the man he sees up there on the screen, somebody who can look out for himself, solve his own problems. I do the kind of roles I’d like to see if I were still digging swimming pools and wanting to escape my problems.” –Clint Eastwood (1978)

AS CLINT EASTWOOD PONDERS WHAT HE’S GOING TO do next, it’s likely that he’ll go back to his own instincts about that ordinary moviegoer—of the laborer who dug out the ground for swimming pools—and ask what he wants. And, of course, that will entail thinking about what women want, women who go out with diggers for a pizza, or women who stretch out by the finished pool with a Mai Tai and a gigolo. Deep down, the audience for Clint Eastwood has always broken down polite talk of social limits and barriers. His movies are like football: They’re about hitting and triumph and the pervasive anti-intellectual, anti-respectable, anti-genteel appeal of power.

In Dirty Harry, for instance, Eastwood goes after a hoodlum at the outset, faces him and challenges him. They are both armed, but several shots have been fired. How many? Eastwood tells him, “This is the most powerful handgun in the world, punk. It can blow your head off.” He asks him to think about how many shots have been fired and whether the magnum has one more bullet left or whether the hoodlum feels lucky. There were those who argued that that scene fostered irrational macho confidence that might stimulate acts of violence; it made the gun a god; it encouraged the audience to trust and desire power.

In the Harry Callahan pictures—Dirty Harry, Magnum Force and The Enforcer—that was a legitimate comment. Harry was a loner who might be bloodied by battle and wronged by the system, but he was impervious, a far steelier superman than Christopher Reeve. We could take his self-sufficiency as a way of life— the lone wolf as a man of honor, possessing a kind of divine knowledge about who was evil in the world. He implied that outlaws were beyond redemption and that the police force was feeble or corrupt. Only Harry could guard the world. “I hate the damn system. But until someone comes along with some changes that make sense, I’ll stick with it,” he said in Magnum Force.

Yet Eastwood heard the complaints. A great footballer can guess how easily he might fill armchair invalids with dangerous dreams about their prowess. Even though the Harry Callahan pictures were big winners, Clint turned off the tap. Indeed, the irony is that his recent flops have been part of a determined attempt to move away from supreme, self-righteous violence to an older man, more tired, less of a success, playing hurt, going for comedy, sentiment and a warmer feeling for frailty and self-mockery. So, as Clint looks at the old trophies and the recent defeats, he must be wondering if he’s going to have to get brutal again. And can someone pushing 55 still cut it?…

… Keep reading on PLAYGIRL+