At 45 years old, The Blue Lagoon is a film both hard to watch and difficult to turn away from. While there is no getting around the fact that the movie would be (and is) considered exploitative today, there’s also something that makes the film beautiful and fragile. This story about two shipwrecked cousins (one already an orphan), who learn whatever they can about life, first from a salty cook, and then as children, alone, stranded on a desert island, without adult supervision, is both controversial and classic.

The film explores taboo themes and has a certain way of sexualizing innocence that can either be viewed as a coming-of-age story, or sensual erotica, with a plot. As we journey through The Blue Lagoon, we bare witness to the children’s evolution from cousins, to kissing cousins, watching them endure/embrace puberty, figure out sex, unwittingly make a baby, and navigate libido and desire without any understanding of what it is, or what to do with it. Both on screen and off, the film’s simplicity borders on naivety, ignoring real questions about trauma, consent, and survival, so much so that Shields, who was 14 at the time of filming, has since spoken openly about her experience, and has, understandingly, also become an advocate for child actor rights.

And yet, beneath the surface of any problematic filmmaking lies something strangely pure: a love story about self-discovery and desire, without societal expectations and opinions. Removed from culture, religion, media, and rules, Emmeline and Richard’s relationship unfolds without the constructs of dating and marriage (the stereoscope they find earlier in the film sets the audience up to ponder the question “is marriage a failure?”). There’s no ghosting one another, no waiting to find out if there’s a better option, no big declarations of love, and no social media for them to show off (or compare) their island life too. Their connection is born from necessity, nurtured by proximity, and tested by the raw realities of life and nature.

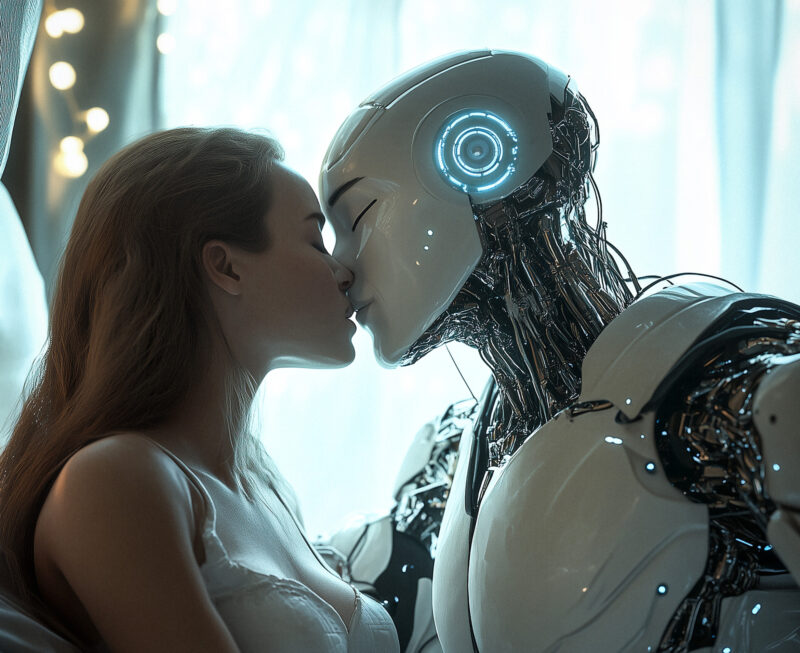

In a world flooded with dating apps, romantic cynicism, and endless advice on love, the film’s depiction of an unfiltered bond feels almost radical. There’s something to be said about being in a world with less options, something that allows us to connect with who and what we have, not what we pine for. It’s a reminder that love, at its core, is not just a feeling, but an ongoing dialogue between people, between our own heart and mind; and that love is an opportunity to demonstrate a connection and devotion to the person who once made you “feel so funny in your stomach.” The film suggests that love is something that grows over time, and that it isn’t something we fall into. To grow and adapt is this real key to love. And in their clumsy intimacy, we are reminded that love often begins not with wisdom, but with wonder.

Would we ever make The Blue Lagoon the same way today? Absolutely not—and we shouldn’t. But whether you see it as a romantic teen movie, or a questionable relic of its time, this flawed fairytale is a reminder of a lost simplicity. In an age where love is often gamified and relationships are filtered through screens, it’s the lack of distractions that feels refreshing to watch. Maybe that’s why it lingers –not because it got everything right, but because it imagines a love untouched by the world.

‘The Blue Lagoon’ • Photo: Columbia Pictures.