When first female Archbishop-designate of Canterbury Sarah Mullally addressed millions of livestreaming faithful from Canterbury Cathedral this October, it should have been cause for celebration. And for millions of progressive Anglicans, the fact that a woman was chosen to lead the Church of England a decade after females were first ordained as bishops was indeed a triumph. More conservative members of the Anglican Communion, however, remain staunchly opposed to this evolutionary step, and have taken the opportunity to dig their heels deeper than ever into the proverbial thorny soil.

In fact, Mullally’s appointment quickly resulted in a schism in the Anglican Church, fueled in no small part by the efforts of the Global Anglican Future Conference (GAFCON), which launched an initiative in 2008 advocating for what it calls “biblical orthodoxy” in Anglicanism. “We have not left the Anglican Communion; we are the Anglican Communion,” GAFCON stated in announcing its break with Canterbury, per The Irish Times.

Considering GAFCON’s history of opposing LGBTQ and gender-inclusive policies, this move was less than surprising.

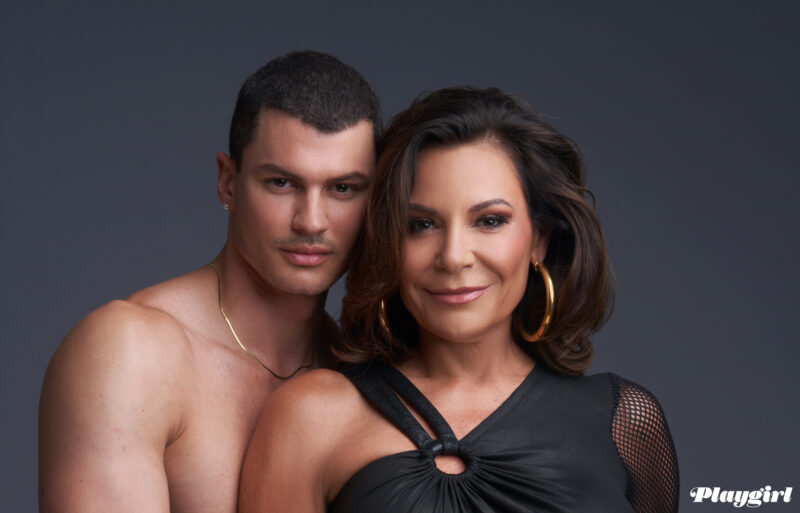

“The election of a lesbian as the Archbishop of Wales and designation of a woman as the Archbishop of Canterbury has been like kerosene on the seventeen-year-old smoldering fire of these tensions with the usual suspects rattling the usual sabers,” The Rev. Canon Susan Russell, diocesan Canon for Engagement Across Difference and a globally recognized lesbian Episcopal priest activist, tells Playgirl.

“The Anglican Communion has historically been a big fat Anglican family of autonomous national churches connected by their common DNA from their Church of England family of origin,” Russell continues. “As a faith community which considers itself both protestant and catholic we are uniquely wired to hold differences in tension.”

As Russell explains, that capacity for tolerance has been tested since the ordination of women in the 1970’s and the ongoing movement for broader acceptance of LGBTQ members of the Episcopal Church.

“As conservatives increasingly lost ground here in the U.S., they mobilized to exploit those differences into divisions in an effort to split the church they were unable to recreate in their own straight, white, male image by fomenting a movement for schism in the Anglican Communion,” Russell says.

There’s no question that Mullally is qualified to lead. She’s already held one of the highest-ranking positions in the Church of England as Bishop of London, earned a Masters in pastoral theology and worked as a nurse before getting ordained as a priest for perhaps the most Christ-like of motivations.

“I became a Christian at the age of 16 and I felt that what I did with my time was, in a sense, to honor God, but also to care for the people that He loved. So that always motivated me,” Mullally told Premier Christianity, adding, “I guess there was always a thought in my mind that I may use my skills in a purely Christian environment, or in the Church of England. But when I was young, the Church of England didn’t ordain women, so it wasn’t really an option.”

As far as her detractors are concerned, Mullally’s extensive leadership experience isn’t enough, nor is her seemingly sincere desire to serve. The backlash recalls the retaliation Katharine Jefferts Schori, former Presiding Bishop and Primate of the Episcopal Church of the United States, faced after becoming the first woman elected as a primate in the Anglican Communion in 2006. Because not all churches in the Anglican communion recognize the ordination of women, her appointment was an unpopular one with some; the Diocese of Fort Worth, Texas, even wrote a letter asking the Archbishop of Canterbury at the time to place them under a different primate, as The New York Times reported.

Katharine Jefferts Schori on the cover of TIME • September 2017.

Now that the Archbishop of Canterbury is a woman, where does that leave those congregations determined to remain stuck in the past? Any progress made will likely go unrecognized, and most definitely unappreciated, by these more traditionally-minded followers.

When asked what unique qualities women bring to the ministry, Russell offers a laundry list of virtues many might consider lacking among much of the clergy.

“Women have expanded the church’s capacity to see God at work in all humanity…leading to broader inclusivity for LGBTQ people, for differently abled siblings and to celebrating diversity in general,” Russell says, going on to add that “breaking down the barrier for women has also created a context where we can see beyond gender to embrace nonbinary siblings and understand that the rich diversity of God’s created order is greater than any binary or hierarchical restrictions placed on God’s grace by human, male dominated institutions.”

As Russell puts it, bringing women into the fold has resulted in a climate where “collaboration rather than competition has become more normative,” and even male clergy members are thriving.

“Inviting women to bring all of who they are to their ministries has also freed up men to bring all of who they are,” Russell says. “And when power-with is valued above power- over, we come closer to the beloved community Jesus called us to incarnate in this beautiful and broken world.”

A common thread among the stories of women like Mullally, Schori, and Russell is that they all grew up during a time when being ordained in the Anglican church wasn’t a possibility for women. Catholic women with a calling, on the other hand, are still limited to the same choices available to them for centuries. Since women continue to be forbidden from being ordained as deacons or priests in the Catholic church, they’re essentially left to decide between becoming a nun or serving the church in some managerial capacity, or both. (This year, Sister Raffaella Petrini was named the first woman governor of the Vatican.)

In 2022, Pope Francis addressed the question of women becoming priests by suggesting the female gender might be better suited to “the administrative way,” saying, “when a woman enters politics or manages things, generally she does better,” according to the Catholic News Agency. He went on to note that women make better judges of character when choosing candidates for the priesthood, explaining, “The woman is a mother and sees the mystery of the Church more clearly than we men. For this reason, the advice of a woman is very important, and the decision of a woman is better.”

“Important” or not, the late pontiff stopped short of believing women were meant for the priesthood, diverging from the German Catholic Church’s Synodal Way, members of which voted to approve a document calling for the ordination of women priests titled, “Women in Ministries and Offices in the Church.”

“It is not the participation of women in all Church ministries and offices that requires justification, but the exclusion of women from sacramental office,” the document argued.

As for the current Holy Father, though his concerns for social justice are in the same vein as his predecessor, Pope Leo XIV has shown himself to be more conservative when it comes to matters of sexual and gender diversity.

Even if Francis wasn’t open to the idea of ordaining women as priests, he did convene two separate study commissions, one in 2016 and another in 2020, about the question of the female diaconate, with the first focusing on historical evidence of women deacons in the early Church and the second diving into the theological implications of this potential shift. Though the results of these commissions were not made public, Francis did say that the first was unable to reach a consensus, per America Magazine: “All had different positions, sometimes sharply different.”

Debating the question of the female diaconate, Francis acknowledged the potentially sacramental role women played in the early church, noting, “There were deaconesses at the beginning [of the church], but [the question is] was theirs a sacramental ordination or not? They helped, for example, in the liturgy of baptism, which was by immersion, and so when a woman was baptized the deaconesses assisted…also for the anointing of the body.”

Sarah Mullally • Photo: Stephen Chung/Alamy.

Cardinal Prevost (now Leo XIV), for his part, stuck to an extremely traditional script when asked about the possibility of women being ordained during the 2023 Synod on Synodality.

“I think we’re all familiar with the very significant and long tradition of the Church, and that the apostolic tradition is something that has been spelled out very clearly, especially if you want to talk about the question of women’s ordination to the priesthood,” he said, according to Catholic World Report.

Leo’s answer harkened back to the proclamation made in Pope John Paul II’s apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis, which stated that, “the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women.”

But how does Leo really feel about women becoming priests, from a theological standpoint? During a discussion on gender equality in the church at the opening of the Jubilee of Synodal Teams and Participatory Bodies in October 2025, he suggested cultural bias was at least partly to blame for women’s exclusion from the clergy.

“Not all bishops or priests want to allow women to exercise what could very well be their role,” he said, per Catholic News Agency. “There are cultures where women still suffer as if they were second-class citizens.”

To Catholics like Miriam Duignan, Executive Director of the Wijngaards Institute for Catholic Research, this justification simply doesn’t hold up.

“The Pope himself recently admitted what we have always known — that there is no theological reason to prevent women being priests,” Duignan tells Playgirl.

“When he claims that the main barrier to women in ministry is ‘cultural,’ he is using a Vatican communications tactic to imply that it is ‘other people in other places’ that could not stand the recognition of women as equals, i.e., the peers of male priests.”

According to Duignan, “this cynical attempt to feign helplessness to enforce change seeks to insinuate that less economically developed locations will not accept women in positions of leadership, adding the sin of racism to sexism.” As Duignan points out, “the opposite is true,” as the “vast majority” of the work being done to keep parishes alive in “the poorest parts of Africa, Asia and Latin America” is being done by women.

Duignan and her colleagues at the Wijngaards Institute are far from alone in their beliefs. In 2024, the final document of Vatican Synod on Synodality expressed the concerns of hundreds of Catholic bishops and laypeople, making note of the “widely expressed pain and suffering on the part of many women from every region and continent, both lay and consecrated, during the synodal process.”

“There is no reason or impediment that should prevent women from carrying out leadership roles in the Church: What comes from the Holy Spirit cannot be stopped,” the document stated, according to Religion News Service.

Though this sentiment seemingly fell on deaf ears, the words ring true: What comes from the Holy Spirit apparently cannot be stopped, considering the growing number of Catholic women who’ve broken away from the Vatican to practice their own form of the religion — the kind where priests can be female — even at the risk of certain excommunication.

The Roman Catholic Women Priests (RCWP) initiative is a movement which “began with the ordination of seven women on the Danube River in 2002” and ordains priests in Apostolic Succession. “The first women bishops were ordained by a male Roman Catholic bishop in apostolic succession and in communion with the pope,” the Association of Roman Catholic Women Priests (ARCWP) website states, adding:

“The Vatican states that we are excommunicated, however, we do not accept this and affirm that we are faithful members of the church. We continue to serve our beloved church in a renewed priestly ministry by welcoming all to celebrate the sacraments in inclusive, Christ-centered, Spirit-empowered communities wherever we are called.”

While the RCWP is revolutionary in its way, women priests have been around for much longer than most people realize. In 1970, during the communist era in Czechoslovakia, Ludmila Javorová was one of several women ordained as a Catholic priest in the underground church when most of the existing clergy were jailed or sent to labor camps. (The validity of her ordination has been the subject of controversy ever since.)

In 1975, over 1,200 people (including nuns) gathered in Detroit, Michigan, for the first Women’s Ordination Conference (WOC) which spawned the grassroots organization of the same name. WOC, in turn, is a founding member of the global umbrella group, Women’s Ordination Worldwide (WOW), founded in 1996.

A Catholic woman called to the priesthood, then, might have more roads to follow than one might think — except for that matter of excommunication. There is no underestimating the gravity of excommunication for a Catholic, but there are those who see this manmade rule for what it is.

“For a faith founded on the teachings of Jesus, a man who was radically inclusive of women contrary to the culture of his time, it remains a tragedy that our church is not only known to be sexist but has now become a magnet and safe space for misogynists,” says Duignan.

Even if a Catholic woman is willing to break from the Vatican and form her own community of faith, though, this solution is limited to the individual level. What of the church’s global influence?

“When the hierarchy admits that women are equal to men, it would be a wonderful sign to the world that sexism is a sin and must now be dismantled — led by the largest non-governmental in the world,” Duignan says.

“Because, the Roman Catholic Church is not only the largest organized religion, it also controls 25% of the schools and healthcare facilities globally,” she continues. “The consequences of an all-male celibate leadership having such huge control over teaching and healthcare without a single women influencing decision making or policy are catastrophic. This is the most urgent issue that the world should be holding the Vatican to account for.”

In the late 1800s, St Thérèse of Lisieux wrote in her diary: “I feel in me the vocation of priest; with what love I would carry you in my hands when, at my words you would descend from Heaven.”

Now, as then, only a priest can facilitate the miracle of transubstantiation, meaning that men alone have the power to turn bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ.