I originally considered another, more allusive headline: “The AI Rush.” The effects of the AI boom may not be as transformative as the California gold rush of the 19th century, but they sure feel like it. Over the past several months, AI artists, AI-inspired and/or AI-labeled accounts have been sprouting up all over Instagram, X, Patreon, Discord… and the apps’ algorithms have been populating my feeds –and everyone else’s– with more and more AI-generated men: some more cartoonish than others, some fantastic, like the “fairy princes” of @mdjrn.charmings, who writes: “In late March 2023 I stumbled upon Midjourney quite by chance and from that moment on she completely changed my life, filling it with the joy of creativity. Art is the interpretation of reality through images. For me it doesn’t matter at all by what means these images are obtained, so I consider myself an artist, I engage in art. Now, as before, my main creative task is to interpret male beauty, both external and internal.”

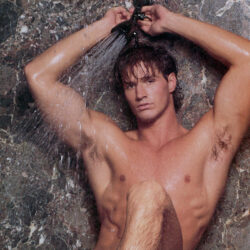

These idealized images of masculinity are nothing but the digital ‘upgrade’, if not of the Renaissance nudes, of the erotic drawings and the paintings and the illustrations and the romance novel covers of the 20th century: don’t @BrawnyAi’s muscular men remind us of Tom of Finland’s and Harry Bush’s? Don’t @mdjrn.charmings’ gothic or romantic settings remind us of Quaintance’s? @HotGuys.AI’s freshmen of Robert W. Richards’? But many AI-generated men and some ‘digital influencers’ are already indistinguishable from us (real human beings) and there’s the rub. Take the fictional (synthetic) Emily Pellegrini: “With her shapely physique and long brown hair, Emily began earning her creator nearly $10,000 in only six weeks on the content creation platform Fanvue,” The Daily Mail reports. “Emily has quickly attracted the attention of rich, powerful and successful men (…) ‘They think she is real. They invite her to Dubai to meet and eat at great restaurants.’”

Image: @HotGuys.AI

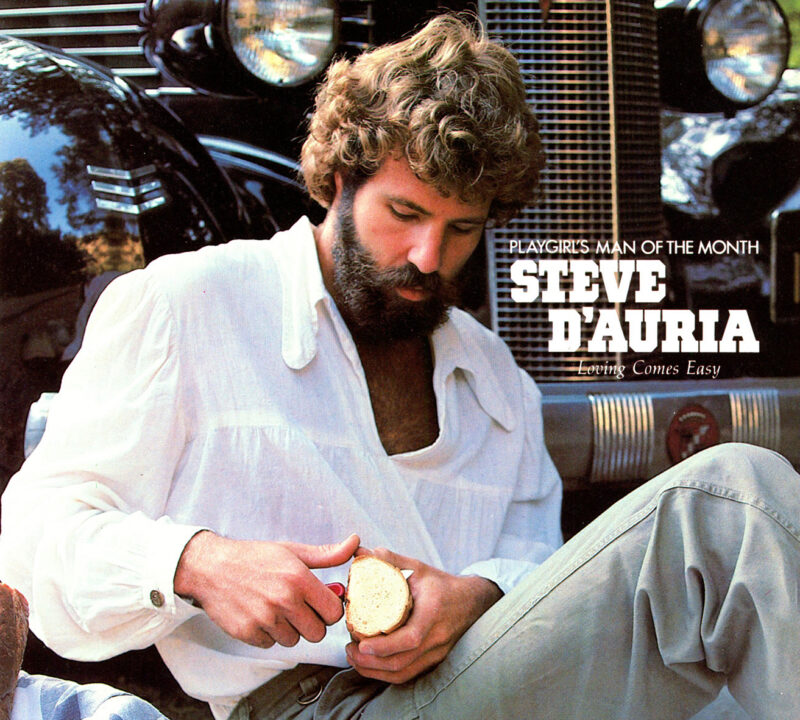

Almost indistinguishable, I should say, because generative AI tools like Midjourney, Dalle-2 and Stable Diffusion aren’t perfect (yet). But they get exponentially better every day and, when blurring the line between reality and digital imagery, they raise a number of questions: ethical and regulatory questions surrounding today’s deepfakes and ‘digital resurrections’; ontological questions about what’s ‘art’ and what’s ‘real’, existential questions about the future of the modeling industry and what we do here at Playgirl.

Photorealism and hyperrealism are nothing new either –in fact, they’re decades old in both painting and sculpture. What’s new is the technology –text-to-image models– fast becoming more and more accessible, and the mass distribution of these digital images on social media. “My ultimate goal is to bring our digital hunks to life through interactive videos and advanced chat bots,” BrawnyAi writes: “Imagine having a virtual boyfriend in your pocket, ready to assist or engage in day-to-day conversations –just like the movie Her.”

Image: @HotGuys.AI

We asked two AI artists to further elaborate on the duality fantasy/photorealism. @HotGuys.AI’s site boasts “photorealistic 100% AI generated imagery. Nothing here is real except for your imagination.” He experiments both with fantasy (his popular “Prince Cousins” series) and boys-next-door (at the gym, on vacation…): “In the realm of fantasy, I’m inspired by the capabilities of AI,” @HotGuys.AI says, “leveraging the abundance of trained models to create idealized, often erotic, representations of men in diverse settings and attire. This freedom allows for the expression of beauty in varied and imaginative ways, transcending the bounds of reality. Conversely, my pursuit of hyperrealism is fueled by a fascination with achieving perfection in imagery, crafting visuals so close to reality that they blur the lines between the actual and the artificial (…) While some audiences prefer the escapism of fantasy, others are drawn to the authenticity of lifelike representations. Both directions, however, are unified in their purpose to stimulate the viewer’s imagination.”

Jonathan P. Jaramillo is the Lead Designer at @MaleModels.AI and @FantasyWrestlers.AI, a studio “that combines AI technology with artistic creativity to design photorealistic, in-the-moment images that celebrate the art of wrestling—genuine moments, peak performance, and the kinetic nature of the sport” and that offers fans a chance to craft the wrestling champion of their dreams. “I was drawn to using AI,” Jaramillo tells Playgirl, “to capture fantasy wrestlers in ways that are realistic and sometimes larger than life (…) We are on the frontier of art-making which allows us to generate lifelike images capturing intricate, human details, down to the drops of sweat on a wrestler’s brow (…) This can be done nearly instantly without the constraints of traditional photography. I’m committed to keeping on the leading edge of what’s possible with AI, and I’m also aware of the apprehensions that come along with it. When photography was first introduced, it sparked debates about realism versus aesthetics and raised moral concerns over its raw, unfiltered capture of reality. Critics argued it lacked artistic merit because a machine produced it. I see parallels between those early criticisms of photography and today’s concerns about AI image generators.” @HotGuys.AI agrees: “There is a disdain for AI images in the art community because people don’t understand the technology. They believe the models are just copying and regurgitating images. This is simply not true. Just as you would teach a child what a kangaroo, for example, looks like, by showing them several photos, you train the AI models the same way. If a child who has never seen a kangaroo, besides pictures, draws a kangaroo, did they copy the photos? The AI uses the training photos only as a reference point to draw new and unique images.”

- Image: @HotGuys.AI

- Image: @HotGuys.AI

- Image: @HotGuys.AI

- Image: @HotGuys.AI

- Image: @HotGuys.AI

- Image: @HotGuys.AI

Two observations pique my interest: a) “without the constraints of traditional photography” and b) the “parallels between those early criticisms of photography and today’s concerns.” A) When shooting a pictorial, one is indeed at the mercy of the talent agency, the location, the crew, the weather, the camera gear…: there are so many variables contributing to a successful layout, but very little control over any of them. Why bother to shoot a real model then? Because of the “splendor of the real” (Godard). We fancy real humans: will I run into them at the grocery store? Will I catch them on the red carpet? Conversely, can the mechanisms of seduction and arousal be set in full motion, if our object of desire is… synthetic? For some of us, perhaps. AI image generators “will offer artists an expanded palette of possibilities,” @HotGuys.AI says. “They will enable the creation of more complex, nuanced and emotionally resonant works, challenging our perception of art and authorship (…) They will open up new venues for artistic expression and storytelling.” But can they replace real models and the human connection they bring to the table?

B) photography first, then cinema, then television wouldn’t be originally thought of as ‘art forms’, insofar they were merely reproductive instruments: they couldn’t have aesthetic value –from an idealistic perspective– because they ‘copied’ reality. The problem with generative AI, on the other hand, is that it “simulates something that has never existed” (Baudrillard): digital “simulacra” with no original. What happens when we can’t tell the AI-generated hunk from the real guy? Shall we be forever trapped inside The Matrix?

- Image: @FantasyWrestlers.AI

- Image: @FantasyWrestlers.AI

- Image: @FantasyWrestlers.AI

- Image: @FantasyWrestlers.AI

- Image: @FantasyWrestlers.AI

- Image: @FantasyWrestlers.AI