The MILF has proliferated in the media landscape like an unknowable specter for decades, calcifying in the collective consciousness with The Graduate in 1968, and dominating the sexual imagination ever since. If Pornhub search term statistics are anything to go by, older women are the most desirable among us, yet this esteem rarely leaves the bounds of the bedroom. The aging woman is a figure paradoxically both coveted and discarded, but always overlooked, reduced to a paper-thin caricature.

It would make sense to take this examination in a Freudian direction, positing that the allure of the MILF is borne from a desire to be nurtured by one’s sexual partner, and that is no doubt a factor in the equation. But I feel the MILF has a parallel magnetism—she’s not your mother, she’s someone else’s, to the extent that the very title of MILF puts her parenthood at the forefront of her identity. To become involved with a MILF is to cause her to deny her most consuming role (at least to the uncritical male eye), catalyzing a sexual transformation from matron to ingénue, thus underscoring one’s own prowess as a sexual object of desire. However you slice it, the MILF has been appealing to the masses solely for her relationships to others, and rarely has she been recognized for her own identity, motivations, and complexities.

However, the tides have turned in the last couple years, as a new wave of MILF movies have hit our screens—or rather, to abandon the term that reduces women only to motherhood and desirability, a genre of films that examines age-gap relationships from a female perspective. To be clear, these films cannot be grouped together without distinction—a subject matter like age-gaps toes a critical line between titillating and criminal depending on the dynamics at play. Todd Haynes’ May December, for instance, is a case study in deluded perversion, unravelling an age gap pushed beyond legal and moral limits. There is no solidarity to be found with an adult woman who pursues a 13-year-old child sexually, and such an act can’t be reasonably compared to the relationship in a flirty drama like the Anne Hathaway vehicle The Idea of You. But what ties these films together is their interest in the minds of older women and the motivations, freakish or otherwise, that propel them towards much younger men.

‘May December’ • courtesy of Netflix.

In May December, Haynes approaches his subject with clinical criticism, but also a delicate pathos that seeks to locate complexity in her behavior. We spend enough time with Gracie, played by Julianne Moore, to see her as delusional, manipulative, and twisted, but ultimately still human. Though refreshing in its nuance, this treatment does elicit a theme with troubling implications—the interplay of age and agency. “You seduced me,” argues Gracie to her husband—“I was thirteen,” he responds. French director Catherine Breillat, whose most recent film Last Summer chronicles an affair between a stepmother and her teenage stepson, boldly claimed in a panel at the New York Film Festival that the story doesn’t need to raise ethical questions about power dynamic, as the woman’s emotional repression reduced her to a mental teenager while the boy’s confidence and maturity put him in control. In seeking to explain these characters’ abuses of power, we’re at a dual risk of trivializing harm and infantilizing older women at large. Certain pathologies can certainly manifest atypical relationships—ones that deserve attention and interest—but it does everyone a disservice to narratively strip these women of agency.

‘Last Summer’

Other, more lighthearted films of the genre—ones which explore age gap relationships that are neither pedophilic nor pseudo-incestuous—are introducing a new trope to the MILF fantasy: the happily-ever-after. Despite the sexual popularity of older women in media, we rarely see them end up in long-term relationships with their younger men. Yet films like The Idea of You and A Family Affair return to rom-com form with resolute affirmations of lasting, committed love by the end. Though, as in many romantic movies, this indefinite resolution may serve to undermine the challenges faced by the couple, there is an empowering undercurrent here. It is not only possible to be wanted as an aging woman, but also to be loved and understood, appreciated not only for your enticing untouchability, but for your vast and unique personhood.

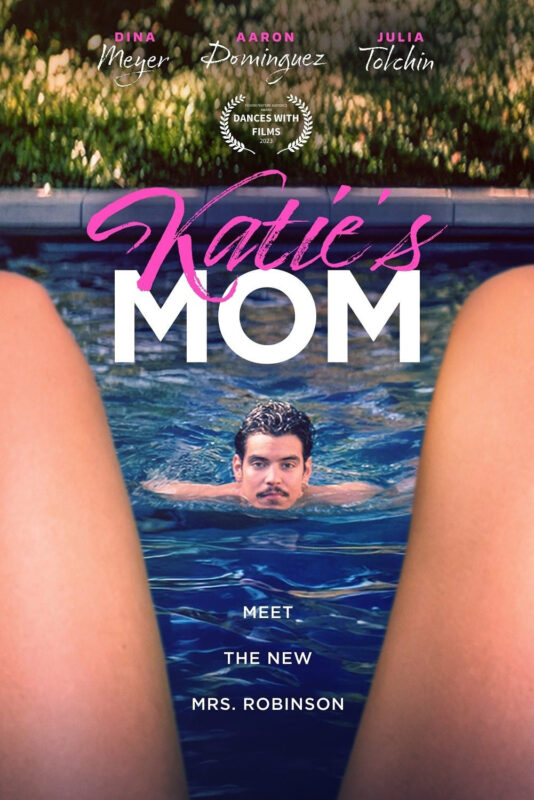

I had this burgeoning and complicated genre on the brain when I viewed Katie’s Mom, the latest induction into the MILF canon. The film follows Nancy (Dina Meyer), a divorcee in the throes of a midlife crisis, who falls in lust with Alex (Aaron Dominguez), her adult daughter’s new boyfriend. I spoke with director and co-writer Tyrrell Shaffner about age-gap movies, complex female protagonists, and the joys and perils of aging as a woman in Hollywood.

‘The Idea of You’ • courtesy Prime Video.

Describe your movie: what is it about?

Katie’s Mom is about a mom who has an affair with her daughter’s boyfriend. We pitch it as a modern day The Graduate from Mrs. Robinson’s perspective, but totally new characters. It’s comedy, it’s fun, it’s light-hearted, it’s sexy. I feel like that kind of relationship is really under-explored from the female perspective. That passion can really ignite you and make you do things you wouldn’t normally do. And it’s wonderful, but it’s also terrible.

This genre of MILF or age-gap films isn’t new, but it seems to be having a renaissance lately. Given the controversial subject matter, a lot of these films of the moment have very different perspectives on the legitimacy of relationships like these. Did you have a particular stance you wanted to portray when making Katie’s Mom?

We felt that Mrs. Robinson was the best character in The Graduate, but she got short-changed at the end. We wanted to explore that dynamic but have you rooting for the woman. We did some story math while writing—her children are very bratty and entitled and no one is acknowledging what she’s going through. She’s recently divorced. Her friends have moved on; everyone has moved on from her. She’s in a really rough place in her life. When we start the film, she’s holding onto the past and can’t let go. So this guy who comes into her life is the only person who is recognizing what she’s going through and really wanting to connect with her, and that’s how he seduces her. It’s not just through walking around with his shirt off showing his abs. In fact, he’s lounging around, eating gelato and being irritating. But he’s very attentive to her when she needs it. We made those choices so you would be rooting for them, but they can’t end up together. For this electrifying affair to change her life, there also have to be consequences. I don’t think they have a deep, lasting love relationship. She is really holding on to her old life, and he’s letting her drop that burden and see a new future in front of her. So he’s a catalyst for her, in a way. This is about a life-altering affair and how that can knock you out of the routines that you’re in.

Many age-gap movies raise questions about agency, power imbalance, and ethics. These characters aren’t necessarily playing the perfect protagonist or heroine or acting in everyone’s best interest all the time. Is that something you were thinking about while writing?

We originally wrote Nancy as more of a doormat in the script, but Dina Meyer is so intimidating and has this toughness to her that made her character a lot more dynamic. About the divorce, people were saying, “This woman should be angrier.” And Dina really brought that anger. Women are always supposed to be likeable, which is so fucking boring. You want someone to be like, “I want to run him over with each of his three cars,” because it shows passion and drive, and it’s relatable.

Those are the best characters, the characters you love because they’re human. I love it when Nancy finally makes a move on Alex. I think that’s a really romantic scene, but she has to make a choice. He sets the groundwork, but she really walks through that door. We wanted to see her make mistakes, but then she does feel bad. She does cop to what she did.

How did you approach the topic of aging in Katie’s Mom?

There’s definitely pressure in aging and how we’re supposed to look. Casting Dina, someone who’s really comfortable in their own skin—other actresses might have not let us show any wrinkles or gray hair. So often when we see older women on screen, all their wrinkles are reduced and smoothed over in post. You can tell, because all the men still have wrinkles, but the older women don’t, because they’re doing a beauty pass and color correction. I was like, we’re not doing that, because that goes against the whole point of the movie, which is that it’s okay for a woman to age. Actually, it’s something to celebrate.

I hope when people watch the film, especially women who are—not even older, like 30s and up—you think about aging more, and know it’s going to be fine. You’re still beautiful, you’re still sexy, you could still make mistakes. There’s a whole journey ahead of you.

‘Katie’s Mom’