In the 1920s, you might hear a newsboy in London or a girl on a playground in New York chant the anonymous ditty:

Would you sin

With Elinor Glyn

On a tiger skin?

Or would you prefer

To err with her

On some other fur?

By the 1920s, Elinor Glyn was the most famous romance novelist in the world. The middle-aged British society woman had catapulted to worldwide notoriety in 1907 with the publication of her novel Three Weeks, about a torrid three-week romance between a sensuous (married!) Slavic queen and a young British nobleman. Famously, the queen forced the young man to watch her writhe on a tiger skin without letting him touch her to ignite his senses. According to Glyn biographer Hilary Hallett, Three Weeks was more explicit about sex than any mass market book before it and made women’s sexual satisfaction a priority.

It’s no wonder that the Famous Players-Lasky Corporation (which later became Paramount) invited Glyn to Hollywood in 1920 to lend her famous name to the movies. Glyn herself was excited to bring her philosophy of love to the masses through the new medium. She told Moving Picture World: “The possibilities of the screen are so great that I am determined to master the art. The moving picture can teach life as it is, and also as it might be.”

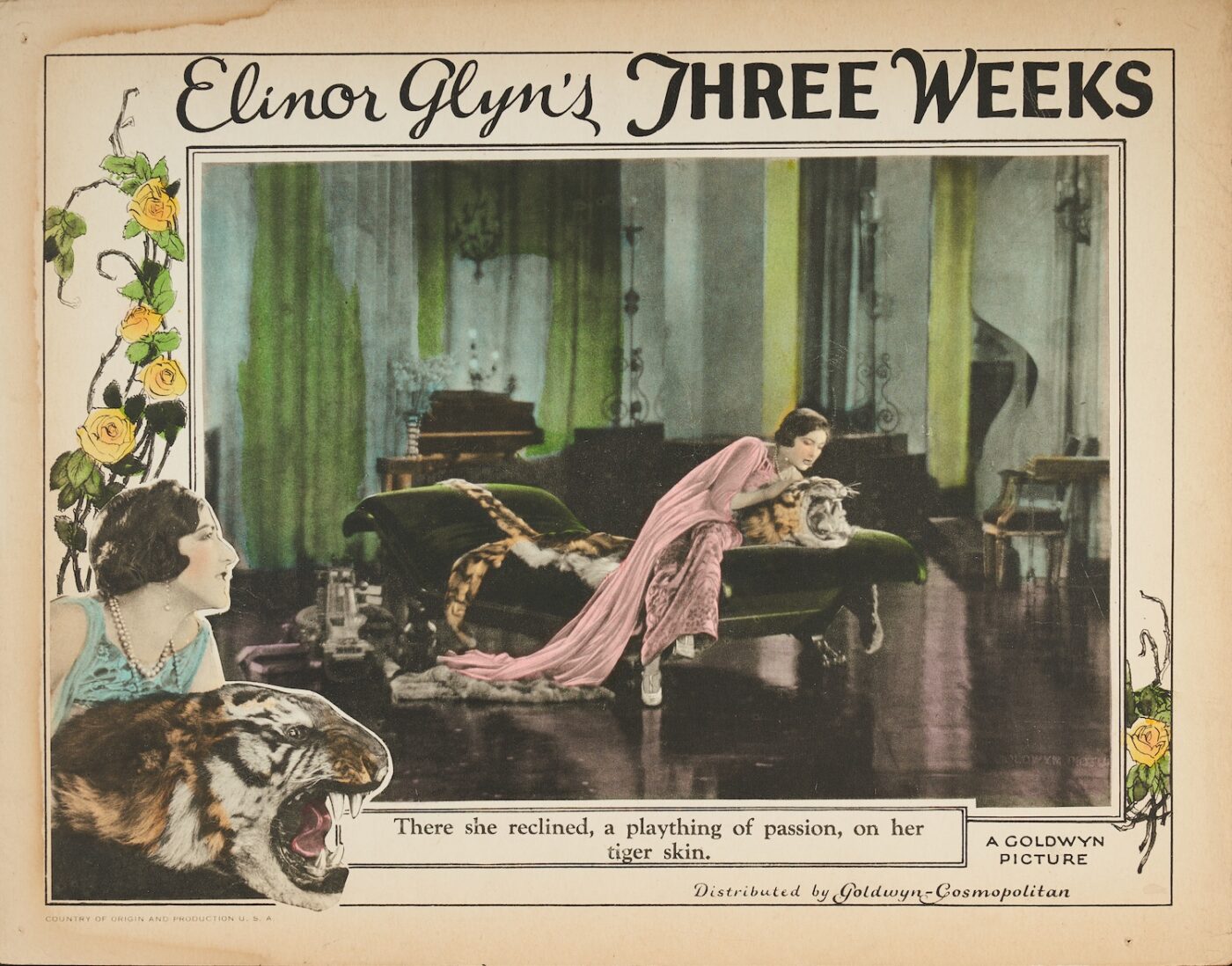

Lobby card of Elinor Glyn’s Three Weeks • Courtesy of the Dwight M. Cleveland Collection.

Once in Hollywood, she wrote, adapted, and supervised eleven movies. According to Vincent L. Barnett, Glyn’s adaptation of the infamous Three Weeks to film in 1924 made twice as much as the average MGM film in the 1925-26 season. In this surviving lobby card promoting the film, which would have been mounted on the wall inside cinemas showing the film, her name is by far the largest. The film is “Elinor Glyn’s,” and if you look more closely, it’s “Elinor Glyn’s production of her famous novel.” She is also credited with the scenario (another word for screenplay).

The lobby card also credits June Mathis—a film executive known as “the most powerful woman in Hollywood”—as editorial director, a position akin to producer. Mathis had written scripts for more than 100 films by this point and worked as “editorial director” at Metro and then Goldwyn Pictures, where she had control over the development of scripts, casting, choosing the director, activities on set, and editing. She is best known for discovering Rudolph Valentino and casting him in Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921), a film that she wrote and allegedly co-directed (without credit). Mathis and Glyn helped shape Valentino’s image on- and off-screen into the exotic, aristocratic, passionate lover that so enthralled female audiences of the 1920s.

Elinor Glyn and June Mathis are just two of the many women writers, producers, and directors who achieved dazzling success in the first years of Hollywood—and whose names are too often forgotten today. Lobby cards like these – a handful of the more than 10,000 cards promoting films written, produced, and directed by over 1,000 women that have been collected by Chicagoan Dwight M. Cleveland – provide a window into women’s achievements in the first decades of the medium.

Feminist film historian Shelley Stamp tells Playgirl that “there was a greater proportion of women in positions of creative control in the first years of the [film] industry than there is today.” She continues: “If you are a young woman making your way in the industry today, you’re not an anomaly trying to break into a male-dominated industry, you’re trying to get back to something that we had.”

A 2023 study by the American Film Institute, “Women They Talk About,” found that women wrote or co-wrote 27.5% of the U.S. feature films released between 1910-1930 and that 19.6% of these films were adapted from source material written by women. They are now undertaking a similar study of short films from this period (a mode that even more women worked in), looking not only at the work of women, but also Black, Indigenous, and people-of-color creators.

It has been claimed that the very first film director was a woman. Alice Guy-Blaché was originally producer Léon Gaumont’s secretary but started directing films in 1896. She directed and produced almost six hundred silent films after that, both in France and the United States.

Alice Guy-Blaché • Photo: Pictorial Press/Alamy.

In the late 1900s and early 1910s, more and more women began to enter the field. Women worked not only as actors, but also as accountants, agents, animal trainers, animators, business owners, camera operators, carpenters, censors, cinema owners, cinematographers, company directors, composers, costume designers, critics, directors, distributors, editors, exhibitors, film colorists, film company owners, film cutters, managers, producers, publicists, sales managers, screenwriters, set designers, stunt people, and title writers. The Women Film Pioneers Project, an ever-expanding website published by Columbia University Library, tells the stories of more than 300 women who held these positions all around the world. This project is part of a groundswell of work by feminist film historians over the last two decades that has revealed the incredible, forgotten work of women throughout silent cinema.

One of the most celebrated women directors of the silent period was Lois Weber. Shelley Stamp tells Playgirl that Weber was “considered one of the three great minds of early Hollywood” alongside D.W. Griffith and Cecil B. DeMille. Whereas Glyn hoped to inspire women and men to adopt a more romantic approach to sex, Lois Weber took a feminist approach to the social issues of the day—issues like the fights to legalize birth control and abortion, to achieve women’s wage equity, and to end poverty, capital punishment, and drug addiction, that we are still working for to this day.

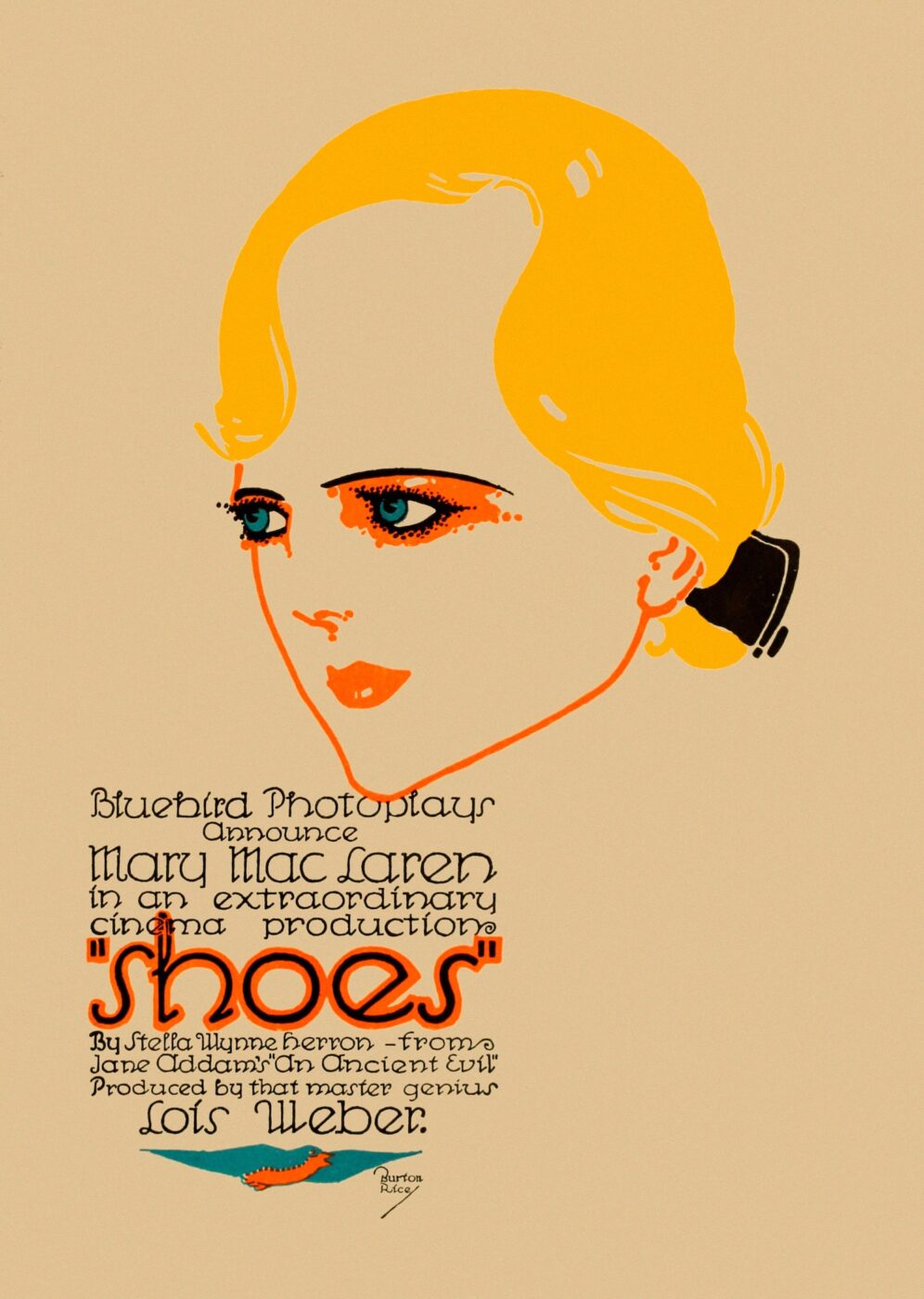

Ad for Shoes • Photo: TCD/Prod DB/Alamy.

This advertisement for Weber’s moving drama, Shoes (1916), about a working-class girl who can’t afford to replace her disintegrating shoes and is therefore lured into exchanging sex for a new pair, attributes the film to “that master genius Lois Weber.” Weber wrote and directed the film and co-produced it with her husband Phillips Smalley. By this point, Weber’s name was associated with quality cinema and films that center the female experience. The ad also emphasizes the other women involved in the production—not just actor Mary MacLaren, but also Stella Wynne Herron, who wrote the short story the film was adapted from and progressive reformer Jane Addams, whose sociological study of working-class and poor women inspired the story. These women used mass media to critique the damaging effects of unfettered capitalism on women’s lives.

Lobby card for Lois Weber’s What Do Men Want • Courtesy of the Dwight M. Cleveland Collection.

Weber went on to write and direct a trio of films in the early 1920s that were, according to Stamp, “really damning portraits of heterosexual marriage.” The second film in the trilogy was What Do Men Want (1921), pictured on this lobby card from Dwight M. Cleveland’s collection. Weber wrote, directed, and produced the film, which critiqued both men’s pursuit of wealth and power under capitalism and their exploitation of women—the wives they neglect but also the women they have affairs with, impregnate, and abandon. In the film’s most dramatic scene, an abandoned, pregnant young woman leaps to her death from a bridge in a public park. The film was so radical that Paramount, whom Weber had a distribution contract with, refused to distribute it, so she went to an independent distributor to get the film out.

When I asked Stamp why Weber and her compatriots have been forgotten, she answered: “The why is pretty easy, you know? The why is because she’s a woman.” Stamp continued: “Her whole generation of female filmmakers has been lost to history and it’s because when the first histories of Hollywood were being written in the late 1920s and early 30s, women were immediately written out of the story. Weber is written out of the first histories of Hollywood while she is still working.” Stamp reflected that the media continued to describe every generation of female filmmakers as an anomaly—Dorothy Arzner in the 1930s and ‘40s, Ida Lupino in the late 1940s and early ‘50s, a whole generation of feminist filmmakers in the 1970s. “I still see it happening,” she remarked.

So, when we applaud contemporary directors like Katherine Bigelow, Jane Campion, and Chloe Zhao for being the only three women to win Oscars for Best Director, we should remember that women were dominating the field long before the first Academy Award was ever given out.

Laura Horak is professor of film studies at Carleton University, author of Girls Will Be Boys: Cross-Dressed Women and American Cinema, and director of the Transgender Media Portal