Gladiator movies have always been there to provide audiences with insight into the power struggles that occupied the Roman Empire and how they reflect on today’s political dynamics. Kidding. They have always been there to provide hot men, in various states of dishabille, sweatily tangling with each other in the arena as thousands cheer. It’s basically combat porn.

The genre reached a peak with Ridley Scott’s 2000 epic Gladiator, which won five Oscars, and turned movie theaters everywhere into arenas where people paid hard earned money to watch the shimmering glads go at it. A sequel was inevitable and it’s finally coming this November, when Scott’s Gladiator II springs its $250 million-plus budget –and splendid sinews–on the frothing public. This time, handsome Paul Mescal is Lucius—the grandson of ex emperor Marcus Aurelius (Richard Harris in the original) and son of Lucilla (Connie Nielsen, both then and now). Lucius is the former heir to the Empire, but nasty General Marcus Acacius (Pedro Pascal) suddenly commands Roman soldiers on an attack that forces him into slavery. This prompts Lucius, thankfully, to battle things out as a gladiator (official definition: “a man trained to fight with weapons against other men or wild animals in an arena”). If he didn’t, there’d be no movie.

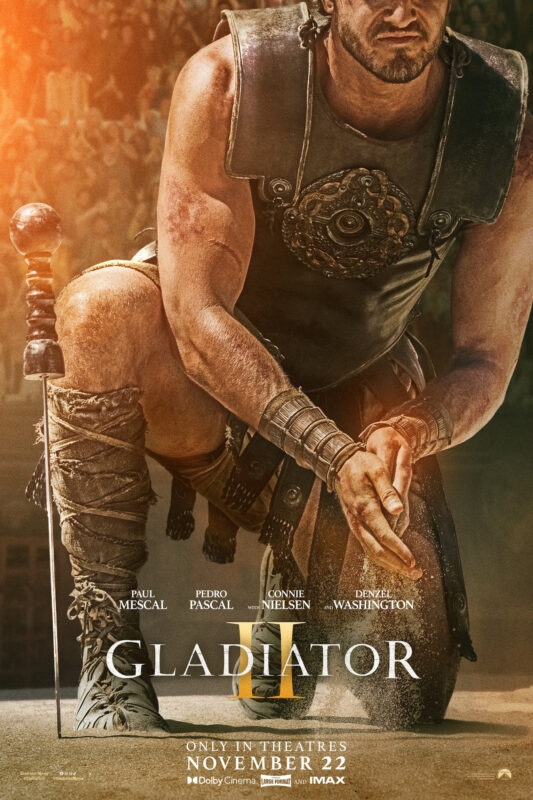

‘Gladiator 2’

These “sword and sandal” films are almost always about a one-time leader who is now a slave but who then transforms into a gladiator to fight his way out of oppression. The perspiring hero inevitably seeks revenge against those who wronged him, while leading the masses in an attempt to overthrow tyranny and find freedom for all! And look hot!

And the genre has always kept topping itself. The extravagant silent film Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925) was remade in 1959 as Ben-Hur, an even more lavish Oscar winning epic full of chariots and chest beating. Hunky Charlton Heston played the titular galley slave in Jerusalem, who trains to be—of course—a gladiator. Dimpled Stephen Boyd played Messala, a childhood friend of Ben-Hur, who eventually becomes a powerful antagonist to him and to freedom. Gay co-screenwriter Gore Vidal later admitted that he had soaked the script with same-sex innuendo. He wrote it as if Ben-Hur and Messala had been lovers, which fascinatingly informs their affections and subsequent rivalry. But director William Wyler knew that stodgy star Heston wouldn’t be too thrilled about playing the story that way, so no one dared tell him about that subtext. They did inform Boyd, however, and in the film, he throws Heston some burning looks that could only come from an ex-boyfriend.

‘BenHur’ • © MGM.

More gay gladiator stuff came the very next year with Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus, which had Kirk Douglas as a Thracian slave leading a revolt with arms akimbo and pecs first. A scene where Douglas battles a 6’4” Ethiopian gladiator (Woody Strode) is stunningly sexy—once you get over the glorified diaper chic, at least. But the most delicious touch of all is the scene in a steamy sauna where aspiring dictator Crassus (Sir Laurence Olivier) comes on to his manservant (Tony Curtis) with all kinds of insinuations and metaphors. The scene was cut, but mercifully restored for the 1991 version, watched by many in the privacy of their own homes.

‘Spartacus’ • Photo: Universal Pictures.

Kirk Douglas already had competition in the torso department, of course. Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954) had Victor Mature as a slave with peekaboo cleavage. In a skimpy green outfit, he alternately battled tigers and romanced Susan Hayward, and since Hayward was tastefully covered up throughout the film, Mature remained the breast in show.

Muscleman actors like Mickey Hargitay and Steve Reeves played Hercules in the 1950s and ‘60s, basically specializing in heroism in togas. And Hercules (played by the beefily appealing Nigel Green) appears in Jason and the Argonauts (1963), about the testosterone-driven search for the golden fleece. The film boasts impressive stop-motion special effects, but the best effects of all were the men’s bodies in revealing outfits, Hercules included.

And gladiator films were hardly restricted to Hollywood. “Peplum”—a name for a Greek tunic– was a condescending term French critics devised to refer to Italian-made films (mostly from 1957 to 1964) which were set in ancient times, like Reeves’ Hercules. These films usually tried to emulate the American blockbusters, though they had also helped pave the way for them; Italian-made epics dated back to Agrippina (a 1911 silent) and Cabiria (1914), set in Sicily.

Decades later, there was even a female gladiator movie, The Arena (1974), a European/American co-production with Pam Grier and Margaret Markov fighting for their freedom in ancient Rome. It was basically a new twist not only on gladiator films, but on the women in prison genre, and it proved that glads’ heaving breasts come in all varieties.

Since then, contemporary stars have tried variations on gladiator films, like Channing Tatum’s attempt in The Eagle (2011), but it didn’t exactly soar. And so, bring on Gladiator II. We’re ready for the flexing, sexy freedom fighters aiming to kick CGI sand in our face.