Whoever built New York’s City Hall knew the facts of life. The only women’s restroom in the entire building is in the basement.

Wandering through the halls, you can tell from the words on the restroom doors who has the political clout in this country—MEN, MEN, MEN.

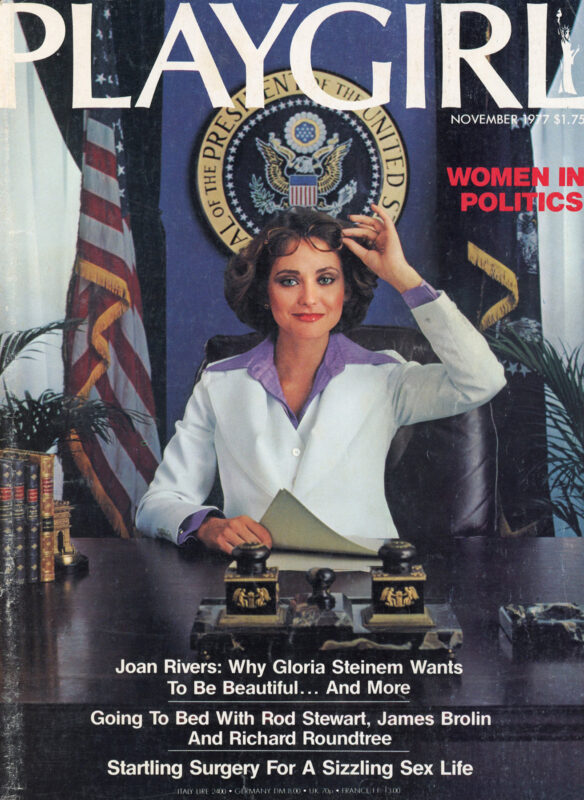

Remember how startling it was to turn on the television and see all those women delegates at the 1972 Democratic National Convention? We’re so used to thinking that politics is for men, we just take it for granted. When a candidate for Governor of California in 1974 wanted to attack his bachelor opponent, he placed ads on the radio that said “Elect and send a real man to do a man’s job.” Several groups could have been offended by that one. But the most interesting thing is that he felt safe in calling the job a “man’s job.” Congressperson Shirley Chisholm (D., NY) recalls that when she first decided to run for Congress, she “was constantly bombarded by both men and women that [she] should return to teaching, a woman’s vocation, and leave politics to men.”

Of course, history confirms that advice. In 1776, when the Founding Fathers declared that all men are created equal, they meant just that—all men. After all, there were no Founding Mothers. Women were denied the rights to vote, to hold public office and to serve on juries. The vote came in 1920, after a monumental struggle to amend the Constitution. Soon after that, women were allowed to hold public office. Restrictions on jury service for women were not struck down by the Supreme Court until 1975. Not exactly a great record for a country that claims to be founded on principles of human dignity, democratic rule and equal rights.

Even winning their political rights hasn’t done much for women. Despite 57 years of women’s eligibility to be President, not one representative of the majority sex has ever been considered seriously for this office. Shirley Chisholm ran a brave campaign for her party’s nomination in 1972, but fell far short of winning. In 1976, no woman tried. Even the Vice-Presidential slot is still ruled out-of-bounds for female candidates. It took a volatile and desperate convention like the Democrats had in 1972 to come close to nominating Sissy Farenthold of Texas for Vice-President. In 1976, the National Women’s Political Caucus and the Democratic Women’s Agenda failed in their efforts to promote a female candidate for Vice-President, dynamic Congressperson Barbara Jordan.

Turning to the Congress, there have been only 20 female senators since 1920. Most obtained their party’s nomination because they were widows of successful officeholders. These women could capitalize on the goodwill generated by their late husbands, attract the sympathy vote and serve as caretakers for the office. Since Margaret Chase Smith (R., ME) lost her bid for reelection in 1972, there has not been a single female voice in the Senate.

Only 18 women serve in the House of Representatives today, as compared with 418 men. Furthermore, these 18 rarely occupy the powerful committee posts or chairpersonships. And when it comes to the informal relationships so crucial to the successful maneuvering and power play within Congress, women again are virtually excluded. They simply are not invited to or welcome at the informal gatherings where information is exchanged, friendships nurtured and promises swapped.

At the President’s cabinet level, only five women have held such rank since 1920, including Carla Hills in the Ford Administration and Patricia Harris and Juanita Kreps in the Carter Administration. In the federal judicial branch, no woman has ever sat on the United States Supreme Court, only one woman sits along with 91 men on the federal circuit Courts of Appeal, and only three of 330 federal trial court judges are female. Women are virtually absent in top positions in all branches of the federal government—positions that carry the responsibilities, the access and the prestige that guarantee influence or authority.

At the state and local levels, women don’t fare much better. Only five women have served as governor of a state since 1920, and three of them served only because their husbands were disqualified. (Remember Lurleen Wallace?) Ella Grasso’s victory as governor of Connecticut in 1974 was a real breakthrough for women, even though she did not present herself as a “women’s candidate.” Three women have been elected lieutenant governor in their own right, including Mary Ann Krupsak of New York, Evelyn Gandy of Mississippi, and Thelma Stoval of Kentucky.

In the state legislatures, the number of women increased from 318 to 685 between 1967 and 1977; but women still constitute only nine percent of the total number of state legislators. In the state judicial branches, the record is no better. Of 10,000 judges in the United States, less than 200 are women. Even in a liberal state like California, where women comprise 53 percent of the population and five percent of the lawyers, women hold only 34 judgeships out of 1167—or under three percent.

At the most local levels, where political office pays less and carries less prestige, women are still grossly underrepresented. Only two women are mayors of major cities (Oklahoma City, OK, and San Jose, CA) and only 400 of 17,000 elected county commissioners are female.

WHY ARE WE KEPT OUT?

This shortage of women at all levels in the political system cannot be explained by women’s failure to vote. Although women have voted less than men in every national election since 1920, the gap has decreased considerably in recent years. In the 1968 election, the turnout of women was 64 percent, and that of men 67.8 percent.

Furthermore, the underrepresentation cannot be explained by women’s lack of involvement in party politics and political campaigns. Most of the volunteer work in political campaigns—the mailings, the organization of social gatherings, the door-to-door and phone inquiries—is done by women. It is when women have wanted to be taken seriously as party leaders and candidates that they have been spurned. As Mayor Moon Landrieu of New Orleans said, “Women do the lickin’ and the stickin’ while men plan the strategy.”

Is the fact that women are not in public office any more significant for women’s freedom than the fact that women are not represented as butchers, railroad conductors or accountants? You bet it is, and for several reasons. We live in a democracy, in which the values and rules that shape everyday life are supposed to reflect the will of the majority. Political participation is the way that we help determine what those values and rules are. For years, women have been told that they don’t really need to concern themselves with that process, that their fathers—and later their husbands—can do their participating for them. If the women would just concern themselves with home and family, the men would protect them. Let them find their place at home, not in the House—or the Senate…

… continue reading on PLAYGIRL+