I never expected to like her. “One does not have a conversation with the woman,” a journalist friend had warned me dourly a few days earlier, “one receives statements.” Moreover, when I had run into her in the past at various California political functions, Jane was aloof, humorless, defensive. You had the feeling that she was one of those individuals where the cable between the head and heart had been somehow disconnected.

“Decadent,” said Jane to the city of Las Vegas as she pushed open the window of her Caesars Palace hotel dressing room. Her puritan heritage seems to rail against the twenty-four-hour, neon-lit pleasure-seeking nature of this place. Wearing a short brown wig, Jane is curled up on a bed. She holds an orange terry cloth robe close to her body, as though to protect herself against the alien environment.

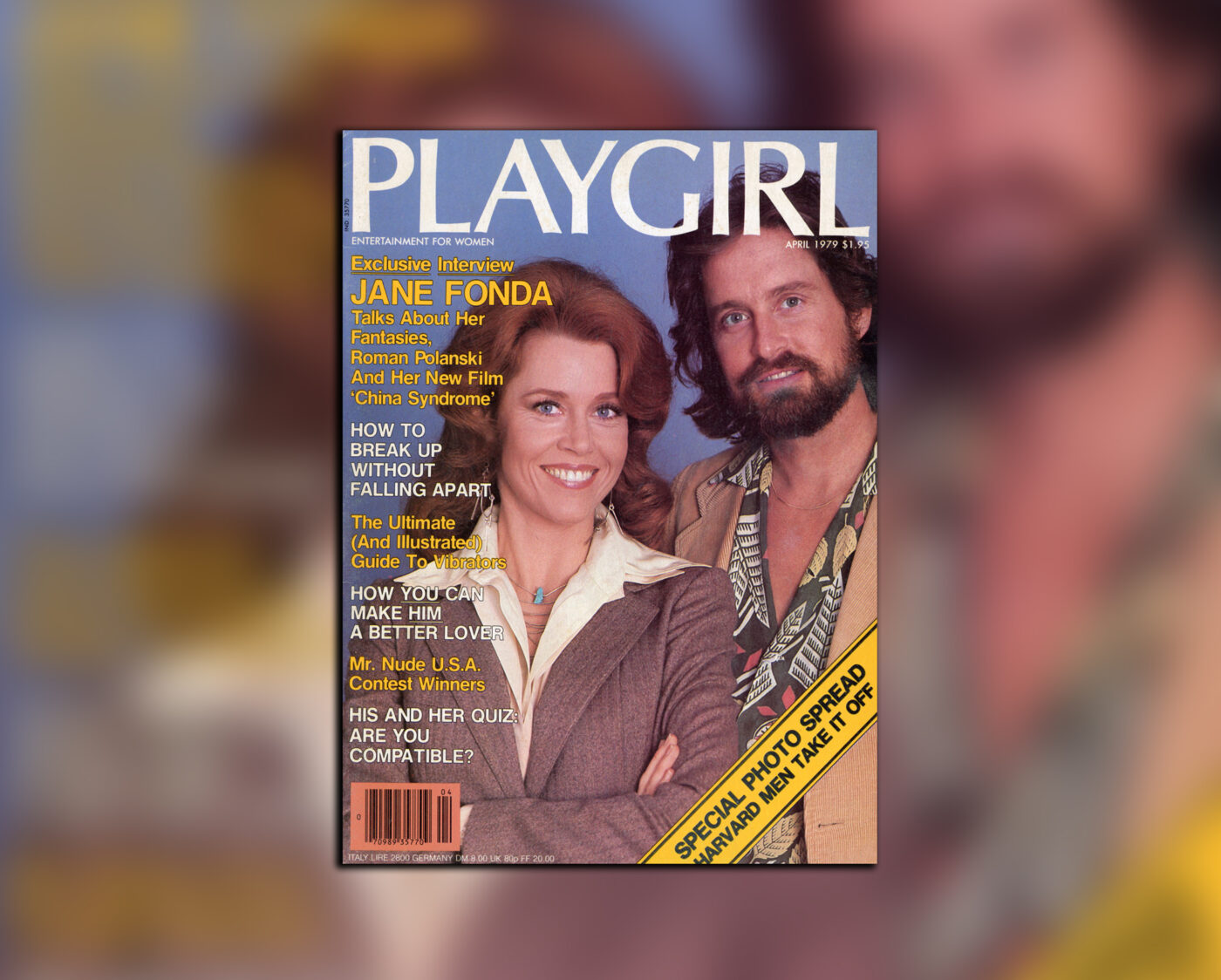

She would have preferred to have been, perhaps, on the phone drumbeating for CED (California Campaign for Economic Democracy), the political organization that she formed with her ex-radical, ex-senatorial candidate husband, Tom Hayden. Or, she could have been happily plotting the release of The China Syndrome with her partner, Bruce Gilbert, and going over the half-dozen or so other socio-politically over-toned film projects they have in the works.

For all that has been printed and broadcast about Jane Fonda, she has said nothing in public about how those events affect her on a personal level. We saw Henry Fonda’s pretty, squeaky clean daughter run off to Paris to marry Roger Vadim, the engaging but vaguely sinister French film director. And we saw her get herself pushed up and platinum haired to be billed as the “American Bardot” in the film Barbarella. We knew that she had Vadim’s baby, but we never knew if it made her feel insecure or alienated or maybe even happy.

Then, she became Hanoi Jane the Iron Maiden, her screeches of outrage at the injustice of the Vietnam War were reported nightly on the seven o’clock news along with miscellaneous mentions that she had been denounced in Congress as a traitor, burned in effigy by construction workers on the steel girders of a Manhattan high rise. A group of Maryland legislators had even half- seriously threatened to cut out her tongue. Who could say if she had married Tom Hayden for love or simply political alliance?

We talked in her dressing room, on the set between takes and while exercising in the hotel’s gym where we rescued a nude, frowzy blond with a snake tattoo on her chest who was overdosing in the steam room.

The interview continued on some of those damn pink champagne flights and somewhere along the way a wonderful, unexpected thing occurred: the vulnerable part of her cautiously began to unfold. Yes, she is arrogant and defensive and she does have to be continually pried from behind the barriers of her intellectual facade. But she is also insatiably curious and funny, with a shy but very deep warmth beneath her aggressive bluster. She told me she isn’t afraid of anything at all but she is just “whistling in the dark.” She is not comfortable by herself and the few silences between us were uneasy, so she hurriedly filled them. But whatever the fears they do not hold her back. Jane forges ahead because she is so absolutely determined to find out what is truly of meaning and value in this world—and then to fight for it. Fear be damned.

Granted, she believes her worry is less now because she has lived through people telling her she’s a crazy, pinko radical, yet only a few years later Johnny Carson introduced her by saying, “Well, we were wrong and she was right.”

In the end I did like her a great deal. In these days when everyone seems so busy cultivating a cool, well-balanced detachment, Jane communicated a sense that it is simply essential to commit yourself to your passions, and if you fall, if the marriage fails, if the work is not accepted with applause, if people are angered. . . you take the risk again because the alternative is to be safe and if there is one thing of which she is certain: safe brings you nothing.

When we began, she was reserved, wary of me, yet clearly ready for business. As I glanced around for an outlet to plug in my tape recorder, she reached out and fumbled behind the bed to help.

Playgirl: People who undergo a lot of change in their lives also seem to do their quota of dumb, awkward stuff on the way to growing up. The difference between you and most people is that you have gone through your personal changes publicly. Is there anything, from Barbarella to Hanoi Jane to the woman you are now, that you look back on with an occasional wince of regret, or maybe embarrassment?

Fonda: I wince at the stridency with which I approached some of the issues surrounding the war, prior to meeting Tom. I figured if I felt so strongly about it and just put it out there, other people would understand— without taking into consideration where a lot of other people were coming from, with all of their problems and fears, their hopes and prejudices. I didn’t have enough understanding or compassion for that.

I can be kind to myself in retrospect and understand the context in which I was shrill. When you’ve lived all your life being told that you should be popular, going out of your way to be liked by everybody … I was a good kid, I hadn’t done anything to deserve being liked particularly, but everyone always liked me. Then, when I began to really do something that was brave, I was suddenly being attacked. I’m thinking of all the different military bases that I was arrested on, where handcuffs were clamped on me, where I had bruises from the guards’ fingers on my arms, where I was thrown on the floor. I was followed and wiretapped and threatened. I literally couldn’t go anywhere without visible FBI guards with holsters and dark glasses following me. If I drove long distances in my car, there would be a helicopter bugging me.

I know I alienated a lot of people. No matter how right what we were trying to do was, there was no way they were going to see beyond the shrillness. It’s that kind of thing that makes me wince.

I go on talk shows now and people say, “Oh, you’re so different now. You’re so relaxed and you’re so human.” But, in my defense, the times are different now than they were then. A human tragedy was going on that I was acutely conscious of. Nixon was in office. And the war was killing thousands of people every day and I just couldn’t tell jokes. I couldn’t be what they call human—to me being human was trying to get the facts out and stop the killing. I guess there must have been a different way to do it than the way I did it. Sometimes I was foolish. And I sometimes now still think about that.

So, now you’re producing films as the medium for your message: Coming Home, about the Vietnam War, and now The China Syndrome, about nuclear power plants. What are your hopes for The China Syndrome?

I think it’s going to do real well in the commercial sense. It works on the level of pure thriller. No matter how you feel about what’s being talked about in the film, the last half hour is gut-wrenching. What I always feel about audiences in this country is that if you can take them on a trip—which is what any good movie is— then it’s scary, emotional or romantic or whatever. If you can add to the trip some values that make people feel that they’ve either learned something or have been alerted to something or if you make them feel better about themselves, then you’ve got a potent combination of forces.

And you think that The China Syndrome is one good example of that?

Sure. It’s about something that’s critical to our lives. People come out energized, angry, scared but not numb, and they’ve been taken on a trip, emotionally. I think it has all the ingredients for a commercially successful film.

Do you think it will motivate people to the point of actually doing something about the nuclear situation?

This is heresy, I know, but I don’t think a film unleashes mass movements or anything like that. As I’m saying this, I’m thinking of Midnight Express, which I’m told actually got people released from prison. It may be possible that a film can concretely achieve something but, basically, I think it is only one step in a certain direction.

Films such as Three Days of the Condor, Godfather II, Rollerball. . . the best example is Network. These are films where a lot’s being said, although you don’t come out thinking, “I was just at a message movie.” Not one of them is going to stop the country, but it’s an accumulated consciousness which I think is going to surface in the eighties. It builds up a new kind of sensitivity in people. Like Coming Home—I get a tremendous amount of feedback about it, at least twenty or thirty letters a week.

There was one letter from a woman who lives with a Vietnam veteran who was suffering from the syndrome—the problem my husband had in the movie. And until she saw the movie, she had assumed that he was just crazy. When she saw the movie, she realized that it wasn’t just him, but what went on there and what those men saw and what they were asked to do. And, you know, she wrote me and said that for the first time she had begun to be able to understand the guy she was living with. . .

Last week I got one from a guy who said that he’s been in a wheelchair—he’d been handicapped in the Second World War— and that he and his wife hadn’t made love in twenty years and they saw the movie and went home and made love. And then lay in bed and talked about it.

Tell me about Kimberly Wells, your character in The China Syndrome. As producer, you had a lot to do with her creation.

At first the main character was a cameraman. Then we came up with the role of this TV newswoman who’s really caught in a bind because she’s not really established, she’s only doing fluff. She wants to do news but they’re not taking her seriously.

We did a lot of research into news. How the networks would take, say, a former model who never even read the paper and change the color of her hair and move her in and sell her like a movie star, because she was the right kind of personality.

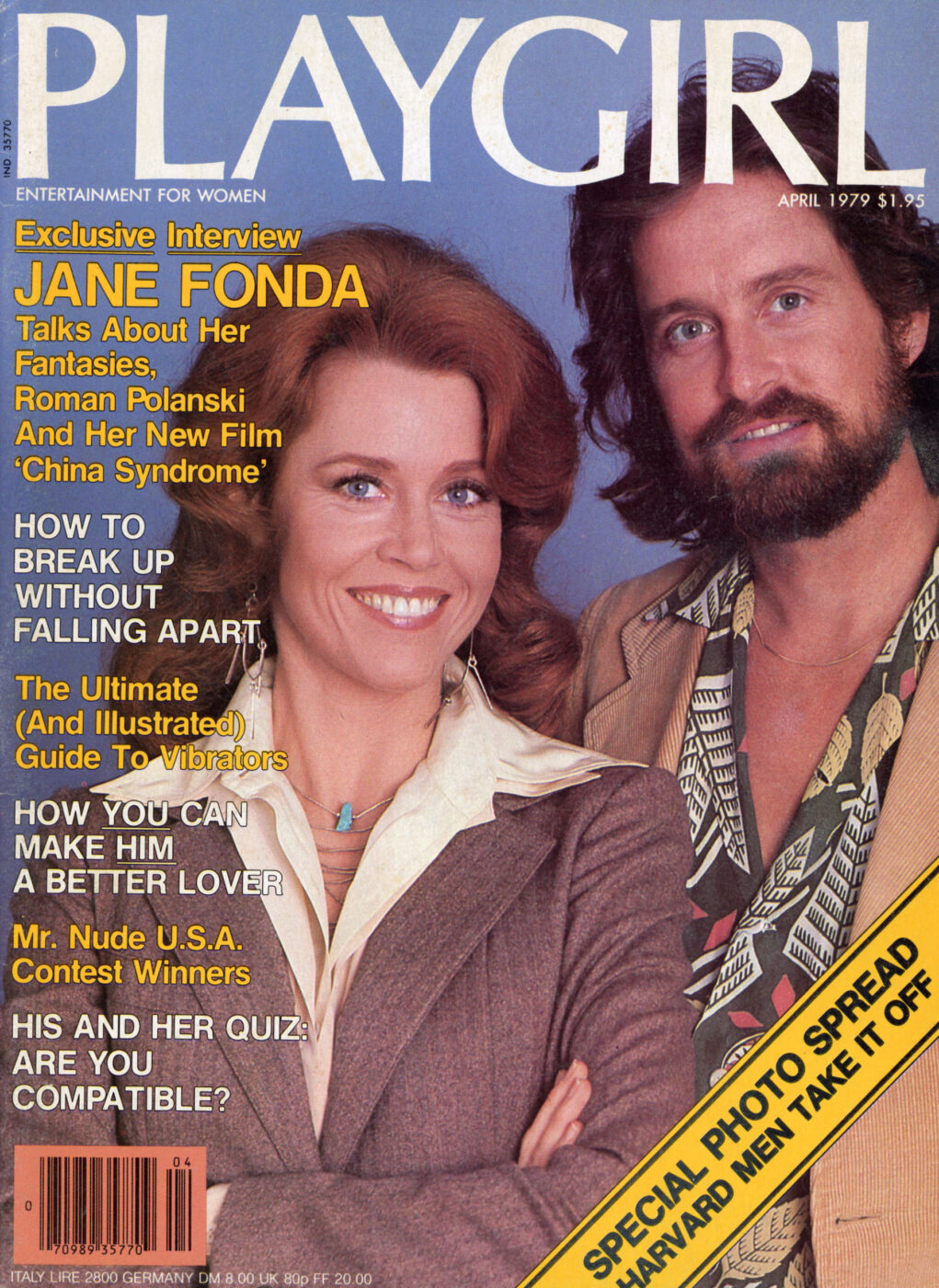

I went and spent time with Kelly Lange and Jackie King and Robin Groth and all of them dye their hair. So, I thought, “I gotta dye my hair.” I said to Tom, “Well, what’ll it be? Should I be a blond?” And he said, “I always sort of fantasized having a relationship with a redhead.” So, I dyed it red . . . my Brenda Starr fantasy…

…Continue reading on PLAYGIRL+