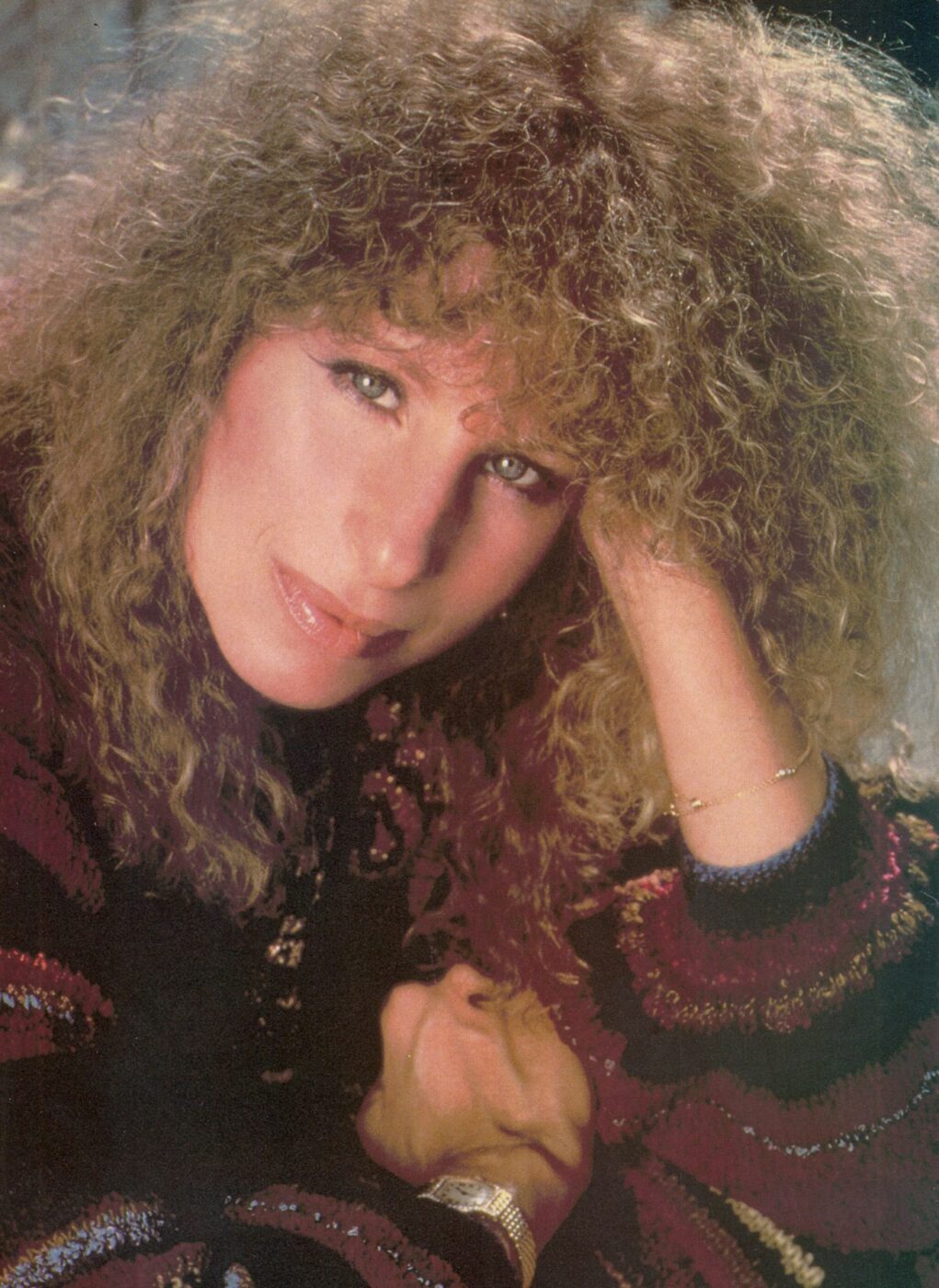

Streisand comes down the hall of her home in Beverly Hills and walks into a room crammed with Tiffany lamps, Art Nouveau sculpture and overstuffed chairs and sofas. Her golden brown frizzy hair shimmers like an aura around her head.

She appears almost preternaturally youthful: She is slim, clear-eyed, with only hints of aging on her face. The maintenance of superstardom for more than two decades seems to have taken a modest toll.

At 41, Streisand has the same magnetism that she did 20 years ago. In person, at least at this moment, the glow seems to come from within, and it has to do with Yentl, her first movie in two years.

Anxious is the cliched adjective for stars awaiting release of their new movies, but Streisand’s anxiety here is more than just another opening of another show. She is the star of Yentl, plus its director, co-writer and coproducer—”the first woman in the history of motion pictures to produce, direct, write and perform a film’s title role,” boasts MGM/UA, which financed and is releasing the movie.

Streisand repeatedly said during interviews that Yentl has obsessed her for 15 years in ways that are intertwined both personally and professionally. And she didn’t seem fazed by the repeated rejections of her Yentl project by the movie studios for which her films have made hundreds of millions of dollars. Yentl, they said, was too Jewish or not commercial, or Streisand was too old and fat to play the girl/boy of the plot.

“I survived it,” she says simply, her voice slightly hoarse from 20-hour days alternating between the recording studio (where she was cutting new versions of four Alan and Marilyn Bergman/Michel Legrand songs from the film) and the editing room, where she was fine-tuning the final version of Yentl.

“I thought that this kind of work would either kill me or make me stronger. And it has made me stronger because I survived,” she concludes.

STREISAND IS NOT THE ONLY ONE surprised that she survived Yentl. Her struggle to make a movie about a young girl who pretends to be a boy so she can study the Talmud (writings of Jewish civil and religious law) in an Eastern European-Jewish community at the turn of the century has won her both ridicule and admiration in the Hollywood community.

“You put yourself at risk when you do these kinds of things,” she says with a shrug of her shoulders. She is nibbling on a watercress sandwich, part of the afternoon English tea ritual that she began in London while editing Yentl. “You have to put yourself at risk. I am prepared for that.”

Yentl is the folktale of a young shtetl (Jewish ghetto) girl, daughter of a scholar, who must disguise herself as a boy in order to study the Talmud. Author Isaac Bashevis Singer, in a Shakespearean twist, has Yentl fall in love with a male student who is engaged to the prettiest girl in the village.

When their engagement is broken, Yentl (still in disguise) marries the girl. Yentl eventually reveals her true identity and embarks for America, where she will no longer have to pretend to be the person she has already become.

Hard-core Streisand fans will be eager to see her onscreen, simply because it is her first film since the financial and critical failure of All Night Long in 1981. (Although there was talk early this year that Streisand would do a concert tour in conjunction with the release of Yentl, a Streisand spokesman said the star has “no intention of initiating or embarking on one.”)

Streisand knows that Hollywood will be watching to see if Streisand the director will be embraced with the same adulation her fans have lavished on Barbra the singer-actress. One studio executive said, “This film will be the real test of star power.”

The Jewish community will be watching to see if a movie that deals with Hebrew prayer and study can find acceptance among mass moviegoers. (Streisand said she hopes “that people in Iowa will go see Yentl because it is not a Jewish movie. To me it is a contemporary film.”)

Feminists are also awaiting the film, not only because they hope that Yentl will demonstrate that you don’t need to be a man to make a critically and financially successful film.

SAID THE STAR IN A LOW, HUSHED voice (Yentl has allowed her to come to terms with the memory of a father she never knew): “I feel like this has released me from the ghost of my father, so that I was able to make him live a little longer.”

Emmanuel Streisand died of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 35, when Barbra was 15 months old. An athlete and an intellectual, he taught juvenile offenders in Elmira, New York, and wrote his doctoral dissertation on Dante and Shakespeare. Written on his tombstone is “Beloved Teacher and Scholar.”

The daughter attributes her drive to make Yentl to a visit she made to her father’s grave. “I’ve had to become my own father,” she explained, still speaking softly. “See, all these years I was just looking for a daddy in a way. And then I realized I was never going to get him. It was only through Yentl that I had a chance to make a father.” The final credit at the end of Yentl reads: “This film is dedicated to my father . . . and to all our fathers.”

“I related to it on so many levels, you know,” Streisand said. “The first four words of the story are, ‘After her father’s death,’ so already I was grabbed.”

As she spoke of her childhood on Pulaski Street in the tough Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, in which her only doll was a hot-water bottle covered with a dress, her carefully sculpted nails dug into the palms of her large hands in a gesture of nervousness.

“I was the only kid on my block with no father. I felt different from all the girls. My mother went to work, and my grandmother couldn’t handle me. She called be fabrent [Yiddish for on fire]. If I was sick with the chicken pox and I wanted to go out and play, I put on my clothes, climbed out the window and went out to play.”

STREISAND CALLS this quality of her personality “power of the will.” It’s what enables her to hold a note for so long when she sings. It is what pushed her to get Yentl made, although every studio in Hollywood turned it down at least once. It is, she said, what makes her Barbra Streisand.

“I remember being a little girl sitting on the fire escape in Brooklyn. I had two best friends, one a Catholic girl and one an atheist. It was so strange, being so young, but we used to have debates about God. One night we were sitting there, with our blankets, and I said, I’m going to show you there is a God. See that man walking down the street? I’m going to pray that he steps down off that curb.”

Streisand was in full pantomime now, reliving the memory in every detail, her hands moving around in a blur. “I mean, I never prayed so hard in my life, you know what I mean? Just, ‘Please show me!’ And the man stepped off the curb. That experience was like . . . there must be a God. The guy stepped off the curb.”

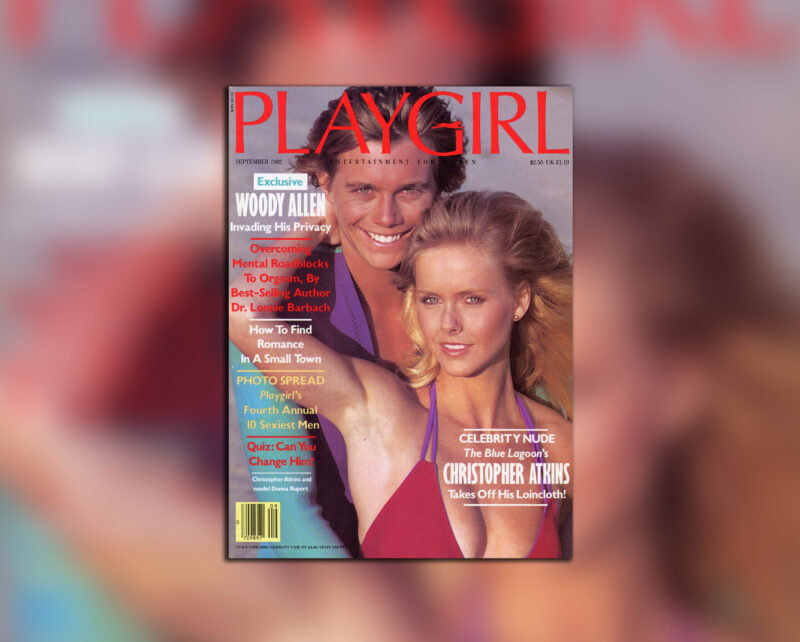

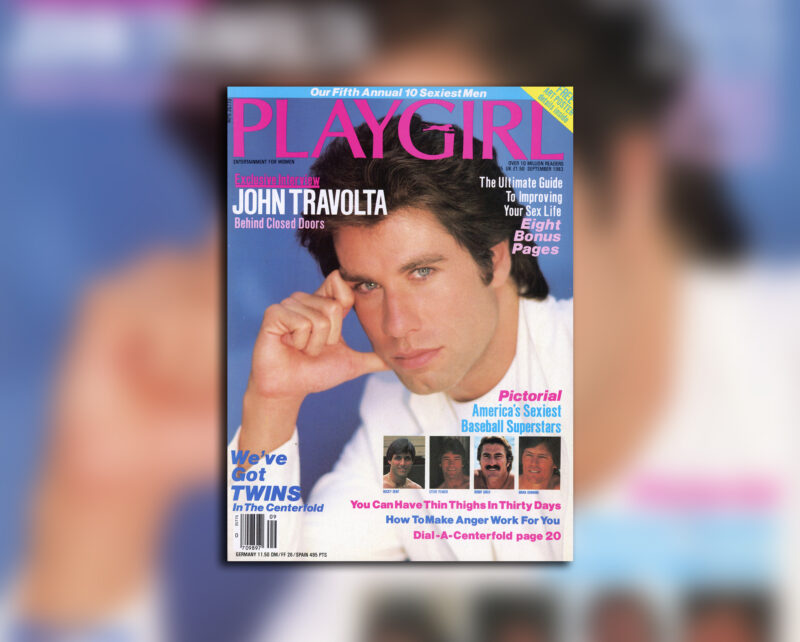

… continue reading on PLAYGIRL+