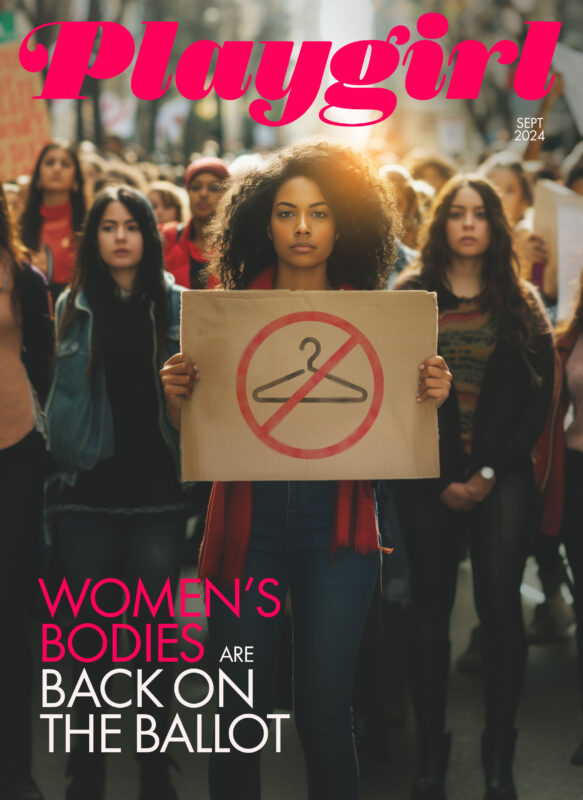

Each presidential election cycle, we’re told it’s the most important of our lifetime. But for those whose bodies become battlegrounds in a debate over reproductive justice, the contest between U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump is deeply personal.

In the lead-up to the first presidential election since Roe v. Wade was overturned, a full third of American voters—the highest percentage ever recorded—say they will only vote for a presidential candidate with matching views on abortion, according to Gallup polling data. That number is up eight points since 2020.

The Supreme Court’s 2022 ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson eliminated the constitutional right to an abortion as established in 1973 by Roe v. Wade and ceded the power to limit or outlaw abortion to the states. Since then, 41 states have abortion bans with limited exceptions. Of those, 14 states ban abortion entirely and 27 states have bans based on gestational age.

“Abortion is a key issue driving people to the polls,” said Ianthe Metzger, senior director of advocacy communications at Planned Parenthood Federation of America. “We expect to see two completely different visions for what the country could look like for abortion and democracy.”

Exploring those visions—and what’s at stake—paints a striking picture of two very different realities.

A ground war over reproductive justice

With 63% of American adults supporting legal abortion in all or most cases and pro-choice voters caring more about a candidate’s stance on abortion than in 2020, Trump—who nominated three of the six judges who voted to overturn Roe—over the summer sought to distance himself from strict abortion language while still taking credit the court’s Roe v. Wade reversal. Despite the lip service, Trump in August indicated an openness to federal regulations to “supplement” state policy. What that could include, from limiting access to contraception to an executive action outlawing abortion, is unclear. But the Republican Study Committee, representing 100% of House Republican leadership and almost 80% of its members, in March 2024 released a budget endorsing a nationwide abortion ban without exception (including rape or incest).

The Harris ticket, which in August brought on Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz as its vice presidential pick, is outspoken in its support for restoring Roe v. Wade at the national level and permanently enshrining it. While running for president in 2020, Harris further pledged to sunset the Hyde Amendment, a law that placed restrictions on abortion coverage through Medicaid. Harris has also been clear in her support for other issues that would speak to a broader picture of reproductive justice—the right to have a child or not and the right to parent in safe and healthy environments—including paid family leave, affordable child care, and sensible gun laws.

“When women consider having an abortion, it’s not just about whether they want a child,” said Rachel O’Leary Carmona, executive director of Women’s March. “It’s the money, it’s child care—a vast amount of people having abortions already have kids… What happens to women—who are the largest voting block in America—what happens to women’s ability to participate in the democratic process, in civic engagement, in the full economy when we don’t have the care that we need, we don’t have the time off of work?”

Playgirl • September 2024.

An ‘incredibly confusing’ landscape

Millions of Americans of reproductive age are now hundreds of miles from the nearest abortion provider, with some forced to travel more than 400 miles for care. More than 170,000 people in 2023 left their home state for an abortion.

There’s more to abortion bans than the distance to clinics. “It’s incredibly confusing,” said Ianthe Metzger of Planned Parenthood. “There’s a patchwork of laws, and your access to care depends on your state… Anti-abortion lawmakers are going even further by restricting people’s travel, making it illegal to help someone go out of state.” “Abortion trafficking” laws, like those passed in Idaho and Tennessee, seek to prohibit anyone who is not a parent from helping a young person leave their home state for abortion care without parental consent.

Less access to care means more self-managed abortions. A landmark study published in July found that 7% of American women of reproductive age attempted SMAs in 2023—up from 5% before Dobbs. Among those in 2023 who said they had attempted SMAs, 11% used abortion pill mifepristone (up from 6.6% in 2022). A variety of other methods were also reported, including herbs, physical methods, drugs, and alcohol.

“We know one of the reasons people turn to self-managed abortions is because access is unavailable,” said Lauren Ralph, an epidemiologist and lead author of the study. “So, it’s not surprising that the number goes up when you restrict that access. The methods used reflect the methods people have available to them that can also offer privacy and convenience.” While the thought of SMAs may evoke violent images from pre-Roe, Ralph called more extreme physical measures “a very small piece of what we see today.”

Access to abortion and reproductive care was uneven even before Dobbs, Ralph explained, and depended on a person’s age, socioeconomic position, and other circumstances. These factors, combined with what Ralph called an “obstacle course” of pending and passed state laws, make for a landscape of reproductive care that is exceedingly difficult to navigate—particularly for the country’s most vulnerable.

The Dobbs decision may have a greater impact on minors, Ralph said, who may be more inclined to pursue an SMA. “They’re just not as familiar with their cycles,” she said. “They tend not to recognize pregnancies until about a week later than their counterparts. That has become an issue in states where there’s a six-week ban, as most people don’t discover they’re pregnant until five or six weeks. That means young people aren’t learning about their pregnancies until that window has passed.”

Today, more than a third of all American women 15-49 years old—and more than half of Black women—live in states either banning abortion or banning it after six weeks.

The need to raise funds quickly, getting transportation to a clinic, and other obstacles to receiving medical care “multiply for young people,” Ralph said. “So, we have to be really attuned to what’s happening to them post-Dobbs.” To be sure: one in 5 women of reproductive age living in a state where abortion is banned knows someone who has had difficulty accessing an abortion.

Ralph also worked on The Turnaway Study, a groundbreaking research project published in 2000 that explored the mental, physical, and socioeconomic effects of unwanted pregnancies on the lives of a representative cohort of 1,000 women.

“We [now] know that if someone is not able to get a wanted abortion, they have almost four times the odds of living in poverty,” Ralph said. “They report being less likely to be able to meet basic living expenses related to food and transportation and housing, so we know there are financial impacts. We also know being denied a wanted abortion keeps people in relationships with people involved in the pregnancy, including abusive partners. The Turnaway Study gives us a really clear picture of what happens if we restrict autonomy to reproductive health care, including abortion.”

Photo: Matt Gush/Alamy.

Working for change from the ground up

“We’re doing everything we can to make the case to the American people and to the media that abortion rights are popular,” Metzger said. But Planned Parenthood’s efforts—along with work from other organizations, including Reproductive Freedom for All and the ACLU, are focused on more than the presidential election.

Local governments have a tremendous amount of sway in a world without a federally protected right to comprehensive reproductive health care. “The states control this until we’re able to get ourselves back into the federal constitution,” Metzger said. “Also state supreme court cases, because so many of these cases come before courts at the state level… Many people don’t realize you can vote for your state supreme court.” Metzger added that Planned Parenthood is also looking at down-ballot races “to make sure when she [Harris] wins, she has the governing majority.”

To Rachel Carmona of Women’s March, these decisions go well beyond laws. “Yes, it’s a policy debate,” she said. “But also, who do we want to be as a country? At the end of the day, what we’re talking about are scared families, scared women… We obviously have to pay attention to policy. But the question is, who are we becoming?”

The next Women’s March is slated for Nov. 2, just three days before the general election for president and capping a day of nationwide Get Out the Vote initiatives. “We are laser-focused on the next 90 days,” Carmona said. Another Women’s March effort, Knock Your Block, seeks to inspire more than 3 million women and allies to get their personal networks registered to vote in this election.

“Everyone has been saying this is the most important presidential election of your life,” Carmona said. “And the thing is, that it has been true each time.”