It all began with their very first books.

For Adolf Hitler, it was Meinkampf. Authored in a period of deep depression, it is a personal manifesto that outlines his racist ideologies and laid the foundation for his rise to power in March of 1933.

For sexologist and sexual rights activist Magnus Hirschfeld, it was Die Homosexualität des Mannes und des Weibes (The Homosexuality of Men and Women). Written early in his career (1916), it explored homosexuality across all cultures and laid the foundation for what eventually became The Institut fur Sexualwissenschaft, The Institute for Sexual Science.

“It was a really pioneering initiative,” says Dr. Lyudmila Sholokhova, curator of the Dorot Jewish Collection at the New York Public Library. “The whole institute was a real breakthrough in the research of homosexuality. And it was so innovative. It was a brave, brave initiative.”

Opened in 1919, it was the first of its kind. Under Hirschfeld’s direction, approximately forty employees researched, wrote and provided courses surrounding transgenderism, transitioning, homosexuality, transsexuality, intersexuality and more. The Institute was acclaimed for its free sex education, treatment of venereal diseases and counseling of thousands of patients who were often seen at no cost. By May 1933, it was a leader in the emerging field of sexology.

By then, Hitler had been named Chancellor of Germany and the Zeitgeist was changing. Young people were being galvanized at campuses across Germany to form the Deutsche Studenschaft, or German Student Union. With a new regime and new laws on their side, these Nazi affiliated student groups rapidly grew. Their purpose was clear: Eradicating anything “un-German” in thought or action. Including books.

For Dr. Sholokhova, their zeal, no matter how biased, was to be expected. “Well, because students, the younger generation, generally carry a lot of energy. And it’s easy to manipulate their minds,” she explains. “And, once you instill some ideas, they carry prejudices. It’s like a fire in their minds and they say, ‘This is who is guilty. This is at fault.’”

As Hitler’s regime began, the guilty ones became the Jewish community. German Librarian Wolfgang Herrmann blacklisted Jewish authors and many others. Rosa Luxemburg, Ernst Glaeser, Sigmund Freud, Ernest Hemingway and Helen Keller are just a few of those, whose works were banned and removed from institutions, public libraries –even private collections.

On May 6th 1933, students, alongside some professors, occupied the Institute and seized all materials. A horrified Hirschfeld could only watch from safety in a Parisian cinema.

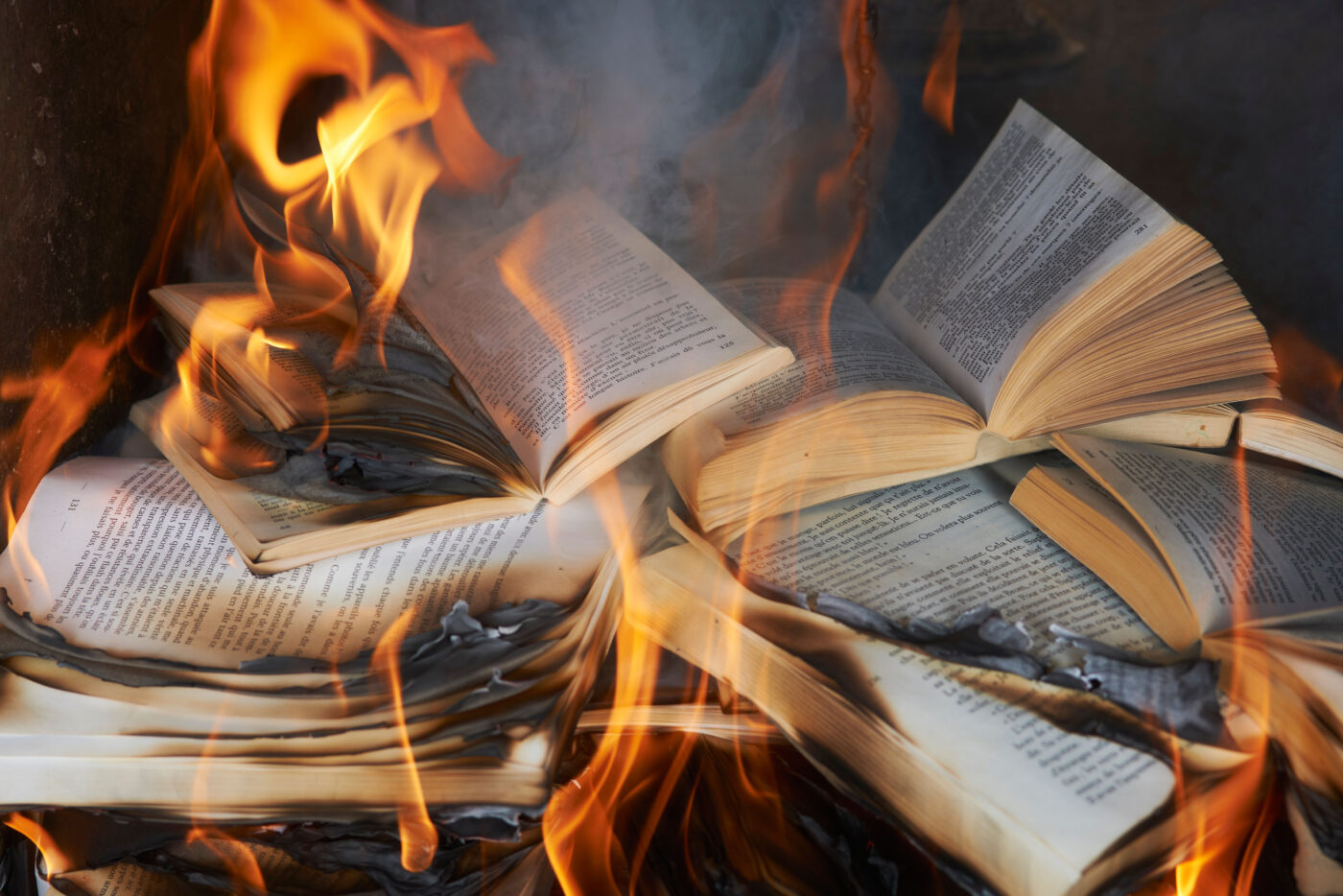

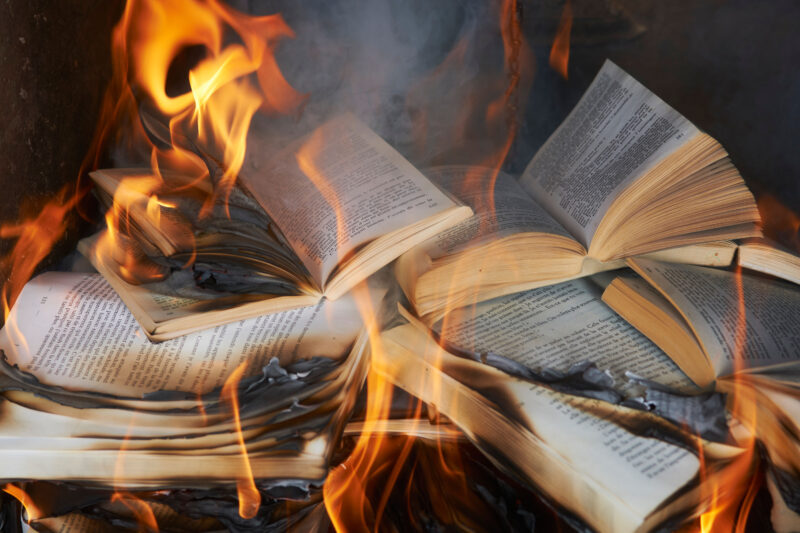

But the worst was yet to come. Four days later, on May 10th, a blaze began. Students, along with professors, gathered over 20,000 books from the Institute and set them on fire in Berlin’s Bebelplatz. Across Germany, students in other cities, towns and suburbs followed suit in a synchronized attack. Before each burning, they recited the “Twelve Theses.”

“It was really very symbolic,” says Dr. Sholokhova . “Because they wanted to show us that they were trying to suppress knowledge. Trying to suppress access to the books. But they also wanted to show that now they rule. It’s to instill fear.” And fear people did.

In the wake of the burnings, persecution against homosexuals, artists and anyone deemed “Un-German” grew. The impact could be felt as far away as America, where protestors and press were aghast. Newsday titled the event “a holocaust of books.” TIME a “bibliocaust” and The Herald Tribune’s Walter Lippmann aptly noted “the ominous symbolism.” History proved them –and many others– right.

In 1935, Paragraph 175, a German statute which criminalized homosexuality, was instated. This law, which Hirschfeld had fought against, led to over one hundred thousand gay men being detained, jailed or sent to concentration camps. Mere years, after the night the books burned in Berlin, we learned that ignoring dictators, rapidly changing laws, and violent action, has tragic consequences.

If any of that feels familiar, it’s no surprise.

Today, a radical change in the political climate seems to threaten the very fabric of our society. But for Dr. Sholokhova, the future is not so dystopian. “I don’t think we’ll get back to this level,” she says. “I’m optimistic. We all will learn something regardless of political orientation.”

For recent college graduate and fashion writer Jacqueline Taylor Nelson, still learning holds true. Nearly a century after that fateful night, she was one of many student tourists who visited the site of the blaze. She describes first witnessing the famous landmark during a five hour tour. “When we first went into the square, it was so beautiful,” she recalls. “There’s so much inspiration everywhere that when you’re looking up at places you don’t think to look down.” Soon, the tour guide walked them to the small, square clear pane of glass set in the ground.

“When we looked in, it was all white, and it was all empty bookshelves. And the guide said this is dedicated to the space that the books that were burned would have taken up if they were still here today.”

Titled The sunken library, it is a permanent memorial designed by Micha Ullman. A tribute to what was lost in the fire, the underground installation reserves enough empty space to house 20,000 books. As many as the books that were incinerated on May 10th 1933. On one of the two small bronze plates set in the ground we read Heine’s prophetic words: “That was but a prelude; where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people as well.”