Centuries before infamous ladies’ men from Mick Jagger to Leonardo DiCaprio made headlines for their copious conquests, history’s most notorious bad boy laid the blueprint for generations of cads to come. Born in Venice to a pair of actors in 1725, Giacomo Casanova grew up to seduce scores of women throughout Europe – from aristocrats to nuns – all while masterfully orchestrating his unlikely ascent to near-noble status. That’s the way everybody thinks the story goes, anyway. But in the case of Casanova, the man and the myth are two separate things.

Casanova’s autobiography, Histoire de ma Vie, tells the tale of a hedonist visionary. His remarkably varied career, or careers, reflected a multitude of identities: He studied to become a priest, earned a law degree, became a violinist, posed as an alchemist, committed elaborate frauds, worked as a spy, escaped imprisonment…and yet, despite his many achievements and adventures, Casanova is known more for his licentious proclivities than anything else.

“He would have been surprised to discover that he is remembered first as a great lover,” Tom Vitelli, a leading American Casanovist and contributor to the international journal L’Intermédiaire des Casanovistes, told Smithsonian magazine.

“Sex was part of his story, but it was incidental to his real literary aims. He only presented his love life because it gave a window onto human nature.”

Casanova’s own nature was filled with contradictions that can be challenging to reconcile: For a man of his time, he was surprisingly invested in the idea of mutual satisfaction and believed women were deserving of sexual freedom; however, despite his progressive philosophy, he didn’t always concern himself with the matter of consent.

On the one hand, Casanova was willing to concede that women could possess higher levels of logic and even humanity than men.

“We have far too much power over women, a veritable tyranny, which we… have been able to exercise only because they are gentler, more reasonable, more human beings than we are,” he wrote.

On the other, Casanova drew the line at the suggestion that females might share a comparable intellect.

“In a woman learning is out of place; it compromises the essential qualities of her sex…No scientific discoveries have been made by women…[which] requires a vigor which the female sex cannot have,” he argued.

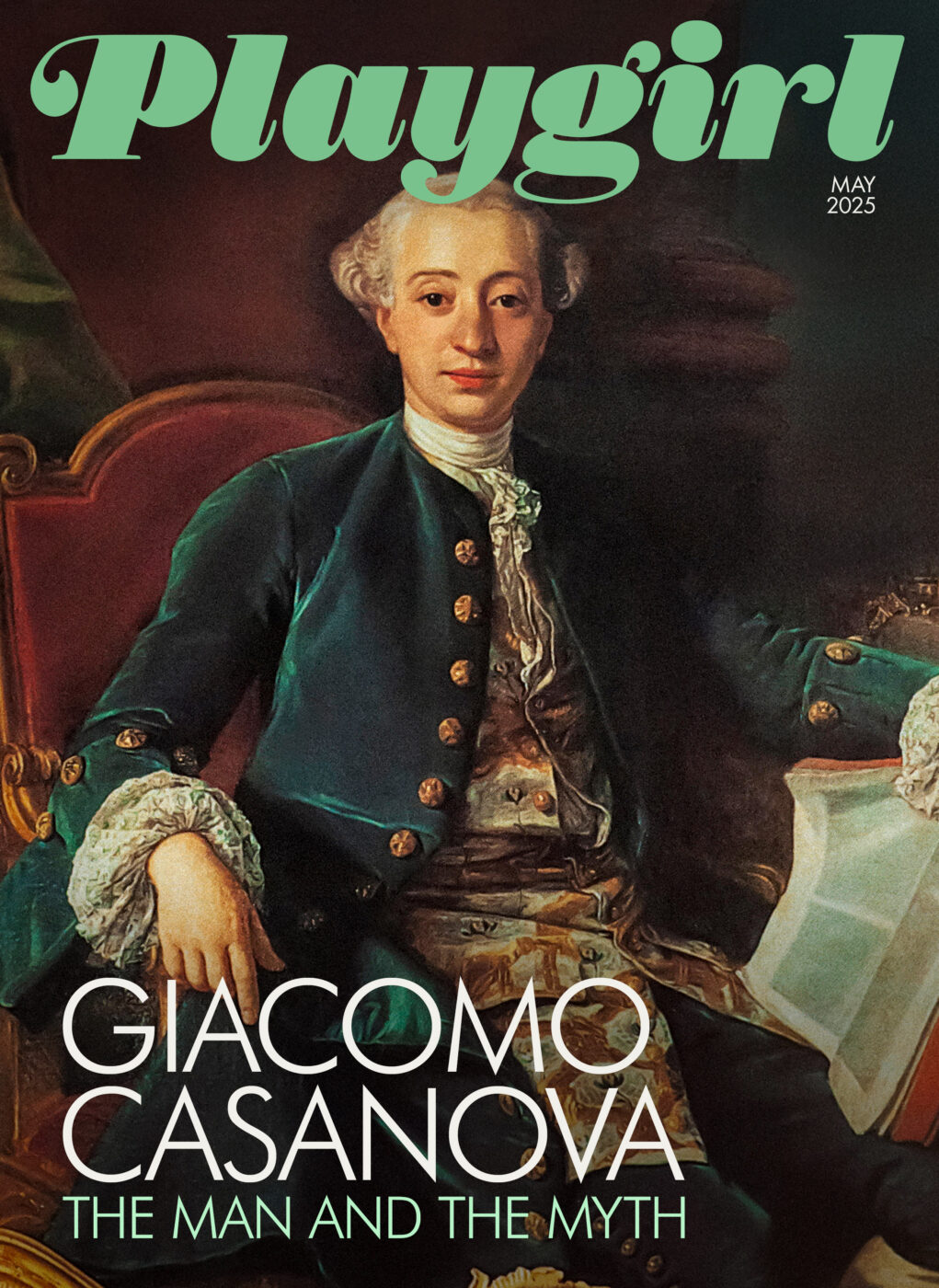

Alleged portrait of Giacomo Casanova by Anton Raphael Mengs.

Of course, this dual-sided attitude towards the opposite sex is a defining characteristic of both Casanova and his behavioral descendants. Casanova types are known for adoring women, sometimes with a dangerously all-consuming fascination. But this fervent esteem oftentimes coexists alongside a lurking misogyny, a simmering contempt expressed through various forms of objectification and even abuse. So how does it all start? What makes a Casanova?

In the prototype himself — and, some would argue, all its later variations — we can reasonably assume certain formative experiences and relationships played a significant role in shaping the future voluptuary.

Luigi Comencini’s 1969 film Giacomo Casanova: Childhood and Adolescence (released internationally as Casanova: His Youthful Years) is a charming, compassionate origin story featuring a series of influential female figures in the sickly, sensitive young boy’s life, beginning with the one who impacted him the most: His free-spirited mother (Maria Grazia Buccella), who was more interested in performing onstage than raising her children.

Though she adored her son, Casanova’s mother ultimately put her own interests first. In Comencini’s movie, we see this early abandonment as the child’s first lesson in how to love and leave, as well as how to heed the call of his own desires above all else.

Casanova’s moral philosophy is cemented later in the film when he gives up the pretense of an ecclesiastical calling for more fleshly pursuits, but we never truly witness the character’s darker side on display. A more twisted incarnation emerges in Federico Fellini’s stunningly surreal Casanova (1976), played by Donald Sutherland (who, it’s worth noting, does bear something of a resemblance to paintings of the actual historical figure). Sutherland’s Casanova, while charismatic, is undeniably creepy, more likely to elicit feelings of disgust than desire.

This isn’t a shock considering the “repulsion” Fellini reportedly felt for the project. According to The New York Times, the director signed on to make the film before reading Casanova’s memoirs. When he finally did, he found nothing sympathetic in his hero.

“There is no ideology, no feeling, no sentiment of even an esthetic character; there is nothing of the 18th century, hence no historical or sociological critique,” he said.

Fellini decided the film would have “a total absence of everything: a funeral‐home film, devoid of emotion, only some figures that take shape in a mass — perspectives scanned in frozen, hypnotic repetition. I desperately grabbed hold of this ‘vertigo in a vacuum’ as my sole point of reference in telling about Casanova and his nonexistent life.”

But was Fellini’s revulsion justified? That depends on who you ask.

Fellini’s Casanova • Photo: Universal.

For some, Casanova’s legend continues to seduce with the same sway the man himself held over his admirers. These scholarly devotees have been willing to overlook, or at least make allowances for, the less attractive aspects of his persona.

“There is not a trace of misogyny in Casanova,” wrote Belgian psychoanalyst Lydia Flem in her book Casanova: The Man Who Really Loved Women. “Women are his masters.”

In The Quadrille of Gender: Casanova’s “Memoirs,” critic François Roustang’s came to another somewhat generous conclusion.

“He is incapable of making the women he deceives suffer — not so much for their sakes as for his own, because he cannot stand the thought that they might no longer love him,” Roustang wrote.

Leo Damrosch, an emeritus professor of literature at Harvard, took a less forgiving stance in his Casanova biography, Adventurer: The Life and Ties of Giacomo Casanova.

“Sometimes his behavior was abusive in ways that are not just disturbing today, but would have seemed disturbing to many people in his own day,” he wrote.

Still, Damrosch gave Casanova a fair amount of credit:

“The mutually gratifying encounters helped him to write eloquently about sexual experience in a way that was unique in his own time and has rarely been equaled.”

Though we have no way of knowing whether Casanova’s interludes were really “mutually gratifying,” in a way, the truth of Casanova’s character lies in the answer to this question.

As Clare Bucknell wrote for Harper’s Magazine, “during the late eighteenth century, ideas around sex were in flux, as Enlightenment rationalists queried the biblical basis for traditional laws prohibiting adultery and fornication, and suggested that even taboo activities such as incest were at least theoretically defensible, so long as they did not threaten the social order.”

Sharing his reaction to a secondhand story of incest involving a man and his daughter and granddaughter, Casanova wrote, “I could not help laughing. I thought to myself…that all the horror that was felt for it came only from education and force of habit.”

Casanova’s final years, while productive, were a somewhat bleak end to a life lived with colorful abandon. After multiple imprisonments and two exiles from Venice, he was forced to take a position as librarian to the young nobleman Count Joseph Waldstein, who lived in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic). In 1789, his doctor suggested that Casanova write his memoirs as a way to stave off depression. The prescription was an effective one: In a 1791 letter to his friend Johann Ferdinand Opiz, Casanova confessed to writing for 13 hours at a time, laughing to himself all the while.

“What pleasure in remembering one’s pleasures!” he wrote. “It amuses me because I am inventing nothing.”

Laughing or not, Casanova was not without disappointments as he reflected on his experiences. “If I had married a woman intelligent enough to guide me, to rule me without my feeling that I was ruled, I should have taken good care of my money, I should have had children, and I should not be, as now I am, alone in the world and possessing nothing,” he lamented in Histoire.

Ultimately, though, he seemed to take responsibility for his fate:

“As for myself, I always willingly acknowledge my own self as the principal cause of every good and of every evil which may befall me; therefore I have always found myself capable of being my own pupil, and ready to love my teacher.”

If Casanova was a teacher, then what are we meant to learn from his life? In reality, “Casanova was a minor character while he was alive,” as Vitelli said. “He was the failure of his family. His two younger brothers [who were painters] were more famous, which galled him. If he had not written his marvelous memoir, he almost certainly would have been forgotten very quickly.”

Casanova proved, quite literally, that anyone can be the author of their own story — and that just might be his most enduring lesson. It’s worth noting that while he was an unquestionably prolific lover, his total number of sexual partners — which has been estimated to be anywhere from 116 to 132 — was not particularly remarkable by libertine standards. Casanova’s salacious secrets aren’t what secured his place in history.

As Stefan Zweig argued in his book, Casanova: A Study in Self-Portraiture, Casanova was gifted with both a story to tell and the ability to tell it — a rare combination.

“Men of action and men of pleasure have more experience to report than any creative artist, but they cannot tell their story; the poietes, on the other hand, must fable, for they have seldom had experiences worth reporting,” Zweig wrote. “Imaginative writers rarely have a biography, and men who have biographies are only in exceptional instances able to write them.”

Through the power of his words, the status Casanova failed to achieve during life was attained after his death, bringing with it a lasting fame that certainly exceeded the man’s wildest expectations — no matter how unintentional his legacy.