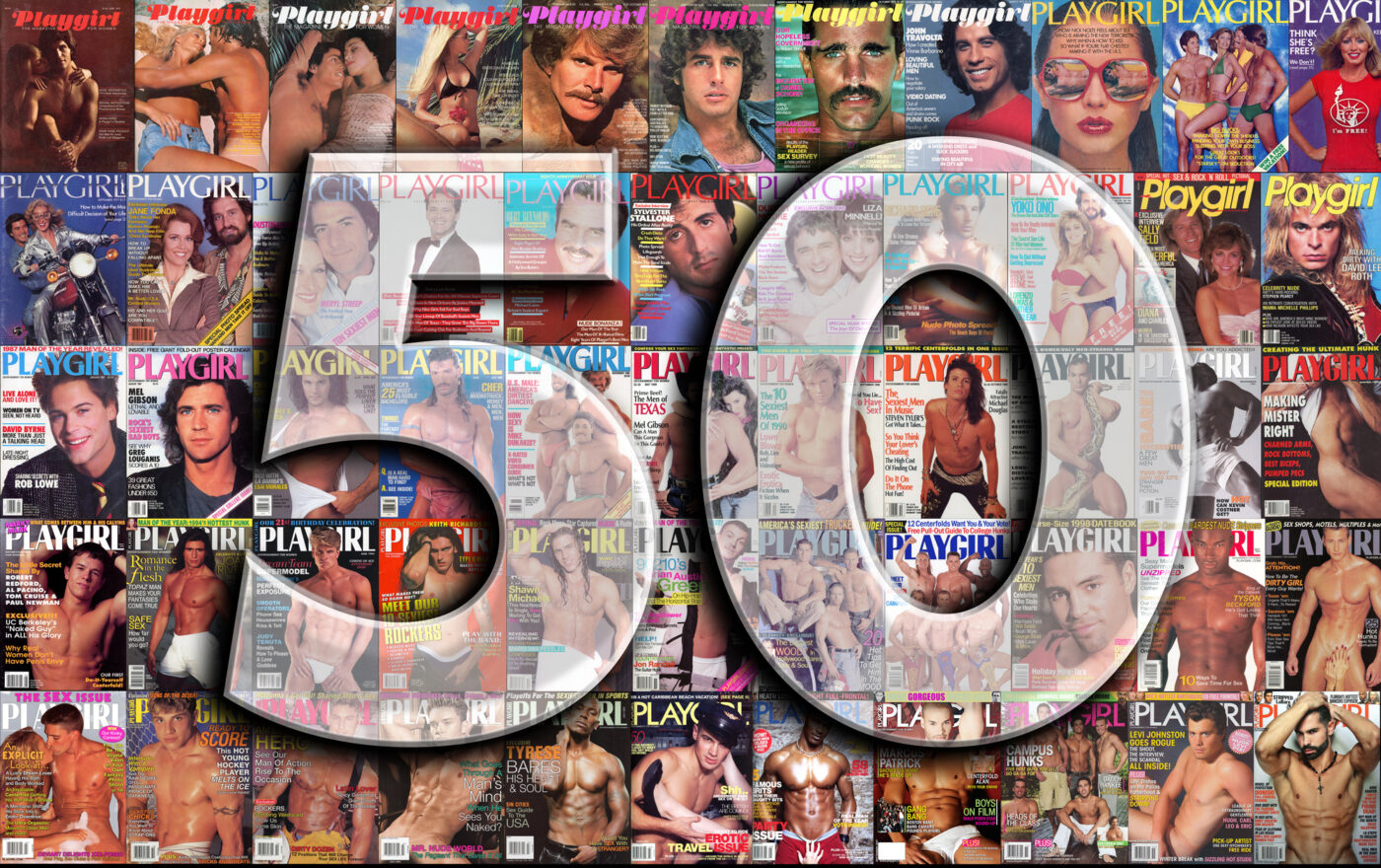

Playgirl returns, reclaiming its seat on the throne as pop-culture titan of bawdy entertainment, on the heels of the brand’s 50th anniversary. The double milestone invites much reflection into Playgirl’s bold, revolutionary, and at times silly and beleaguered, history.

From its inception, Playgirl has been—without question—one of a kind. The magazine stands as the first mainstream periodical to recognize women as independent sexual beings with voracious visual appetites. Playgirl offered a safe and very singular harbor to explore one’s sexuality while flipping the idea of the male voyeur on its proverbial head. Without Playgirl there is no magazine of “Entertainment for Women”—and there certainly will never be one to match its rich and varied history.

Playgirl is also symbolically important. The brand reimagined who women could be and mirrored those ideas back to them. Installments over the years featured interviews with some of the country’s most prolific, inspiring women from Gloria Steinem to Dolly Parton. Playgirl was ahead of its time, too. The magazine covered “The Myth of the SuperWoman” more than 40 years before Meta’s former COO Sheryl Sandberg shortsightedly told women to simply “Lean In” to have it all. Even when Playgirl’s brand authority diminished, or its target demographic blurred, the brand’s impact on American feminism and sexuality in the last half-century simply cannot be overstated.

Playgirl made its debut in 1973 with the feminist movement at full tilt, its first issue landing on newsstands just six months after the Supreme Court’s ruling on Roe v. Wade. Back then, housewives were rebelling and birth control was newly legal, but the U.S. was still more than a year away from allowing women to take out credit cards in their own names.

Playgirl’s premier installment featured an undressed and dimly lit Lyle Waggoner (The Carol Burnett Show) looking straight into the camera. A blonde woman behind Waggoner, his body blocking hers, ignored the camera as her downcast eyes instead examined her male subject’s neck and her long fingers encircled his bare shoulders. The racy cover represented a colossal role reversal of well-established art history and the portrayal of gender roles in American media.

The first installment of Playgirl sold out. Instantly.

Revolutions are complicated things, of course, and women—and their flagship entertainment magazine—were no different. If magazines and brands function as reflections of the cultural times they’re born into, then it’s fair to argue that Playgirl shared in women’s struggles in the last five decades to assert a clear stance on what empowered sexuality could look like for women and the broader population.

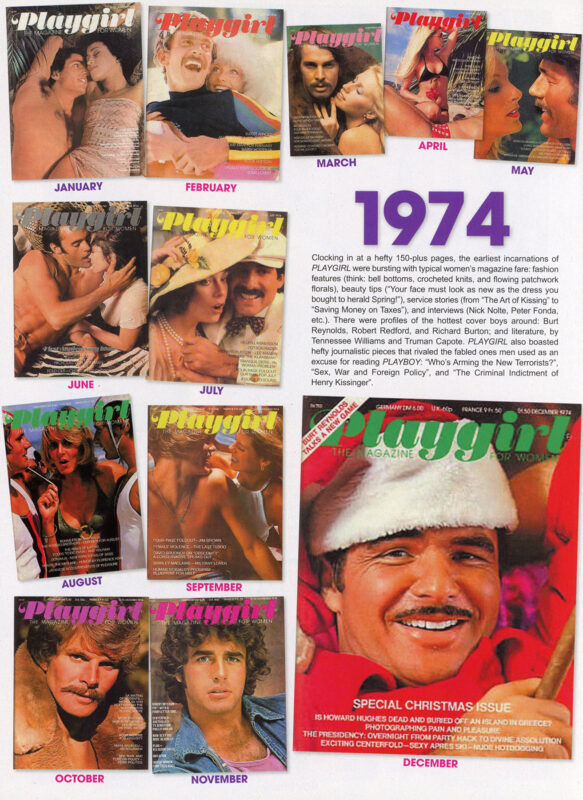

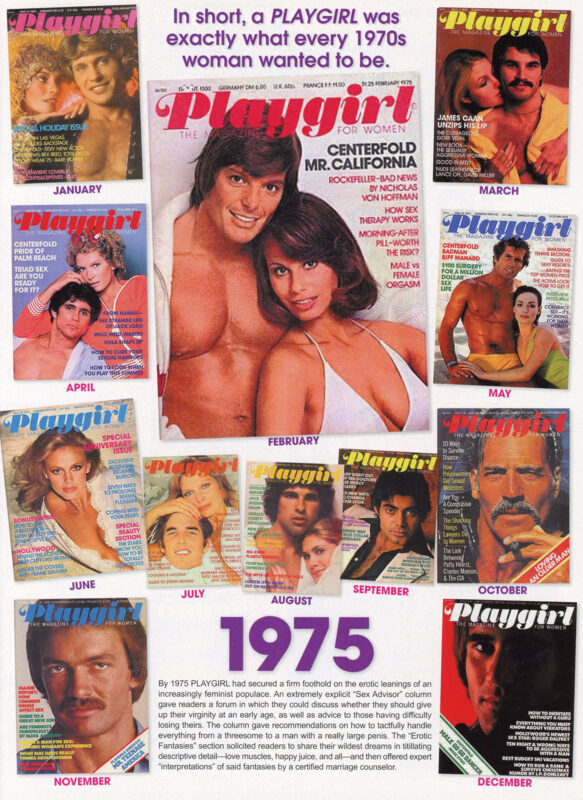

Playgirl wrestled with an obvious, early paradox: If sexuality is so individualized, how can one magazine possibly please everyone? Within Playgirl’s predominantly white, middle-class purview, the glossy often fell short of its purported goals. You can see the magazine’s evolution over the decades; from 1970s snapshots of lean, mustachioed men with body hair to the blonde and hunky ‘erect ‘80s’ (and even a dismal ‘clothed’ year therein), to the celebrity lookalikes and beefcakes of the ‘90s, and group photo sets of “campus hunks,” controversial paparazzi shots of nude a-listers, and men in uniform throughout the ‘00s. There was virtually no way to land on the exact right place as the needle moved; but anything good is worth fighting for, and Playgirl’s editors over the years certainly did that.

Playgirl spent a half-century mirroring our desires and curiosities back to us, often in a way that was highly collaborative. The magazine had sections for reader-submitted erotic fiction, wildly popular “Real Men” entries, “win a date” contests with Playgirl models, and sex and relationship advice. Fundamentally, Playgirl sought to make sex fun for everyone. Articles explored political issues and women’s health alongside frank discussions about masturbation, polyamory and fantasy. With each installment’s multiple photo sets, women (and a growing, gay male audience) were encouraged to look without embarrassment and openly explore their sexual proclivities. Playgirl’s modus operandi of inviting its women readers to not avert their eyes and to be explicit about what turned them on opened the door for other underrepresented groups to bravely do the same.

Fifty years later, we can see the fruits of that labor. Even women who didn’t open a single issue were touched by Playgirl’s influence as other media rose around it, suddenly less encumbered and far less modest because of the work Playgirl did.

My tenure at Playgirl (2006-2015) came at a new kind of inflection point for women. In this world, we had six seasons of Sex and the City glorifying single, working women and casual sex, and a newly formed movement called “me too.” Playgirl’s pages reflected this new era of empowerment as the staff pushed for clothed-female-naked-male couple sets, more diversity among the models, and more in-depth feature coverage of women’s issues as seen through the lens of health, politics, and lifestyle. Our small, all-female staff was deeply committed to what we saw as the brand’s feminist mission—the risqué photo shoots, issue-release parties featuring scantily clad male models and phallic desserts, and the endless stream of adult novelty items landing on our desks for review were just the proverbial cherries on top.

For all the magazine’s boldness, whimsy, and challenges, Playgirl holds an entirely serious and massive space in the histories of sexual empowerment, feminism, and the expansive LGBTQ+ movement. That’s because Playgirl planted its flag in the American timeline and tore a hole wide open in the country’s fabric. It spent a half-century as an ally for millions of people vying for visibility in a world that has done all it could do to stick to the status quo.

Playgirl‘s progress (and regressions) have been well-documented. As the media, low-brow and high, mulled the point of Playgirl throughout the years, so did the people I met every day during my time there: “Who is Playgirl for?” they’d ask. “What is it trying to do?” And, most commonly: “What is it like to work there?”

Everyone. Everything. And heaven.

The publication may never get womanhood totally right, or the perfect female gaze, or what it’s like to look out into a world that never before expected or wanted you to look. And for all that imperfection, something perfect emerges: a canvas on which to paint something new.

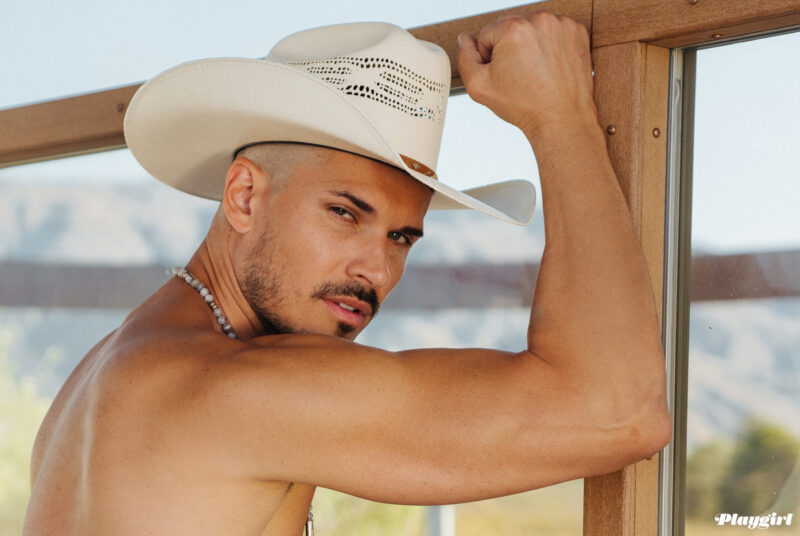

The latest incarnation of Playgirl offers fresh energy and perspectives on contemporary feminism, sexuality, and the male form. It also takes into account today’s media landscape and its challenges while presenting an iterative take on an exciting formula long overdue for another, lingering look.

Thank goodness for that. Cheers to another 50 years.