Since its premiere in 1926, Puccini’s opera has suffered both the “slings and arrows” of its exotic pageantry, and the “insolence” of ‘innovative’ stagings, which often bore no relation to the libretto and/or the score. I saw a few traditional, opulent mise-en-scène (beginning with Zeffirelli’s at LaScala in 1983) and too many reinterpretations/rewrites: director Lorenzo Fioroni had Turandot and Calaf kill their parents at the Berlin Deutsche Oper; Nuria Espert had the princess commit suicide at the Gran Liceu/Barcelona; inspired by a few hints in the libretto (“Turandot doesn’t exist,” “the face you see is an illusion”), Barrie Kosky decided she was never to be seen on stage at the Dutch National Opera…

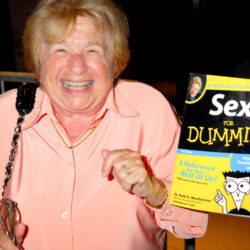

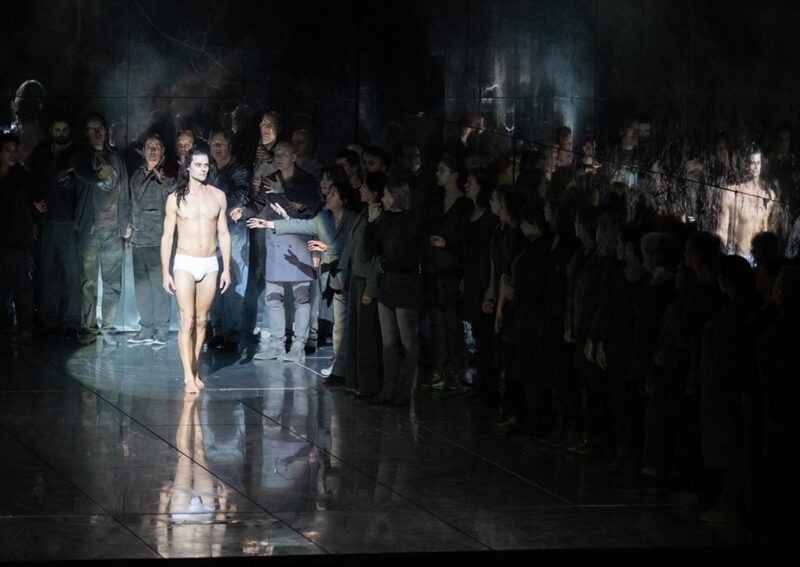

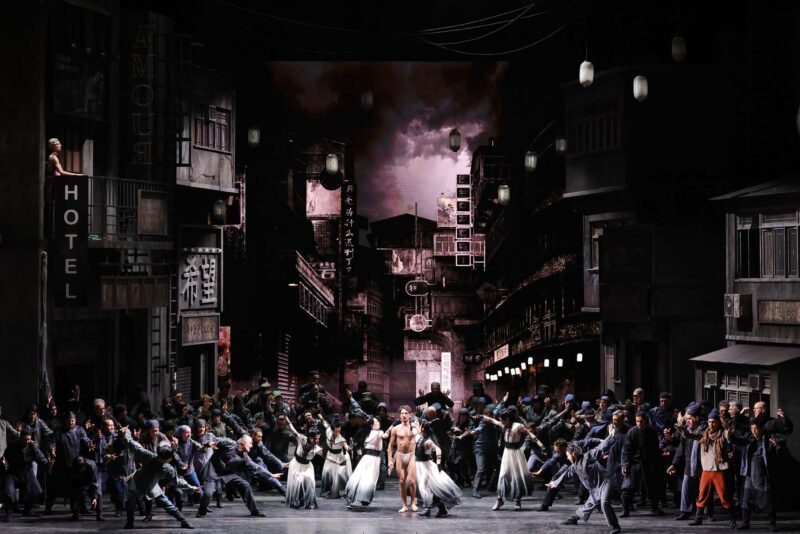

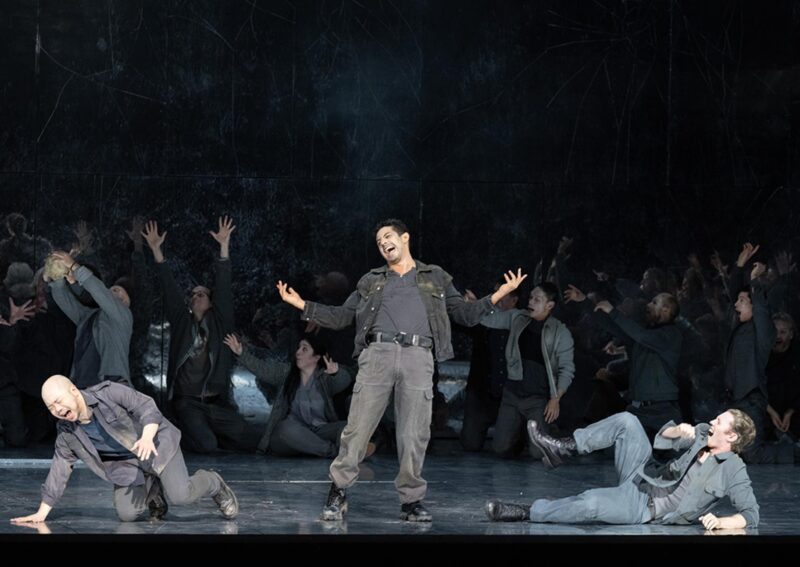

Photo: Dutch National Opera, Turandot 2022 (© Monika Rittershaus).

What’s the problem with these productions? Zeffirelli followed the original stage directions to a T; he understood that Turandot’s pomp and circumstances aren’t merely decorative –they’re indeed foundational– and yet they swallowed the characters and their humanity. Fioroni chose to highlight the dynamics of gender and power, but the finale with the assassinations clashed with Alfano’s bombastic score and with the lyrics: “Love! Sun! Life! Eternity! Love is the light of the world! Our infinite happiness laughs and sings in the Sun. Glory to you.” Turandot’s suicide made dramatic sense in the Espert production –it was consistent with her pride (“No one will ever possess me”), but it betrayed the opera’s premise: “As Turandot’s ice melts,” the composer wrote, “the scene (…) is transformed little by little (…) where the crowd, the Emperor, the court and the entire ceremony are ready to welcome Turandot’s cry of love.” And, not unlike Fioroni’s finale, it clashed with both the score and the lyrics. Asynchronous music is often used in films to great effect, but it is jarring –to say the least– in opera: can we listen to the choir singing “our infinite happiness” and, at the same time, watch the princess die? Kosky did away with “Peking in legendary times” and with the Alfano finale, ending the opera with Liù’s funeral cortege instead. Historically accurate (Puccini died) but artistically false: what of the thawing of Turandot? What of the love theme? The final duet, according to Puccini himself, “has to be the highlight (…) The duet! The duet! Everything decisive, beautiful, vividly theatrical is there.”

Turandot sketch by Franco Zeffirelli, Fondazione Franco Zeffirelli.

“Turandot has enormous challenges,” opines Kosky. “Musically, dramatically and culturally. How to deal with Puccini’s colonialistic attitudes towards the East? How to deal with an opera that’s ripe with misogyny? How to deal with an opera that is unfinished?” Let’s unpack these questions: 1. “Unfinished.” Turandot was posthumously completed by Alfano, after Puccini’s sketches (36 pages) for the duet and the finale. That duet, that hymn-to-love and that triumphant finale which Puccini had long yearned for and had always eluded him. “We must get to a final scene where love explodes,” Puccini wrote his recalcitrant librettists. And again and again: “I think the dramatic core is the duet.”

It’s well known that the composer was dissatisfied with the many drafts of the duet as written by librettists Simoni and Adami and that, musically, he had not solved the enigma of Turandot’s transfiguration from “princess of ice” to “flame and ardour.” Yet, hints of the princess’ humanity –and the seeds of her catharsis– are for everyone to hear in act II, when Turandot recounts the murder of her ancestress: “And Lo-u-ling, my ancestress, dragged off by a man like you (…) In you I avenge that purity, that cry and that death.” Puccini writes “dolce con dolore” in the score (‘sweet with pain’). Listen to Joan Sutherland’s high B when she sings “that cry” and you’ll know the abyss of sorrow in her soul. The frailty and the wounds behind her pride. As always in opera, the dramatic truth is found neither in the plot (often absurd), nor in the lyrics (often inadequate and Simoni/Adami’s are no exception here); it’s found in the music.

Photo: Dutch National Opera, Turandot 2022 (© Monika Rittershaus).

2. “Colonialistic attitudes.” “Turandot is a masterpiece that contains imagined, outdated and inaccurate representations of Asian culture.” LA Opera felt it necessary to print this ‘disclaimer,’ when they reprised the 1992 Hockney production earlier this year. Yet Puccini wrote of “an ancient, legendary, almost fantastic Chinese subject.” A fairy tale –not a representation of any particular culture– where Peking “in legendary times” is no more “imagined” than Shakespeare’s Verona or Elsinore or Rome… Far from exhibiting “colonialistic attitudes,” the composer explored China with great musical curiosity and went out of his way to research traditional Chinese themes –eight made it onto the score. All too often, contemporary metteurs en scène rush to allege Puccini’s cultural appropriation but aren’t in the least concerned with their own: they see the speck in Puccini’s eye –if there ever was one– but not the log in theirs. When Kosky spurns each and all stage directions, when he abuses the author and perverts his artistic intent, is it all just ‘reinterpretation?’

Photo: Brescia and Amisano, Teatro Alla Scala.

3. “Ripe with misogyny.” It is true that Puccini referred to Turandot, in his correspondence, as “la fredda donna” (the ‘cold woman’) and “la principessa crudele” (the ‘cruel princess’): “Calaf must kiss Turandot,” he wrote, “and show his great love to the cold woman,” who refuses it. He does kiss her forcefully in act III: “carried away, Turandot has no more resistance, no more strength, no more will power. This unbelievable contact has transfigured her.” But Puccini also took inspiration from a Max Reinhardt production of the fairy tale, where the princess was just a tiny woman, surrounded by much taller men. It’s no coincidence that eight sages appear in Puccini’s act II, “grave, enormous and imposing.” Here’s laid out –visually– Turandot’s war of the sexes.

Photo: Dutch National Opera, Turandot 2022 (© Monika Rittershaus).

Musically and dramatically, conductor Von Karajan saw the princess not as the imperious, hieratic protagonist we know, but as a “little girl, prisoner of her imagination,” observes Carlo Marinelli, “which she defends (…) from any interference with an intolerance that is not perfidy, cruelty or power hunger, but rather a terrified fear.” She avenges her ancestress (“The horror of her assassin is still vivid in my heart”) and, at the same time, she fends off her suitors, rebelling against a patriarchal system which sells her off in marriage. When Calaf solves all three riddles, she protests to her father: “You can’t give me to him, to him like a slave, ah no!” And to Calaf: “I shall not be yours! (…) Would you have me in your arms by force, reluctant and enraged?” For that matter, does Calaf’s ‘love-at-first-sight’ amount to anything more than lust and a rabid desire to possess? “O divine beauty, o marvel, o dream (…) I want you to be mine.” Calaf wants her princess “ardent with love,” he kisses her in a frenzy, he conquers her, he re-enacts, in her eyes, the “ancestress’ torment.” Part Salome, part Herodiade, part frightened child besieged by men, young and old, Turandot fights for her survival in a hostile male world: a far more complex character –more modern and, we dare say, almost proto-feminist– than she’s often played.

Photo: Dutch National Opera, Turandot 2022 (© Monika Rittershaus).