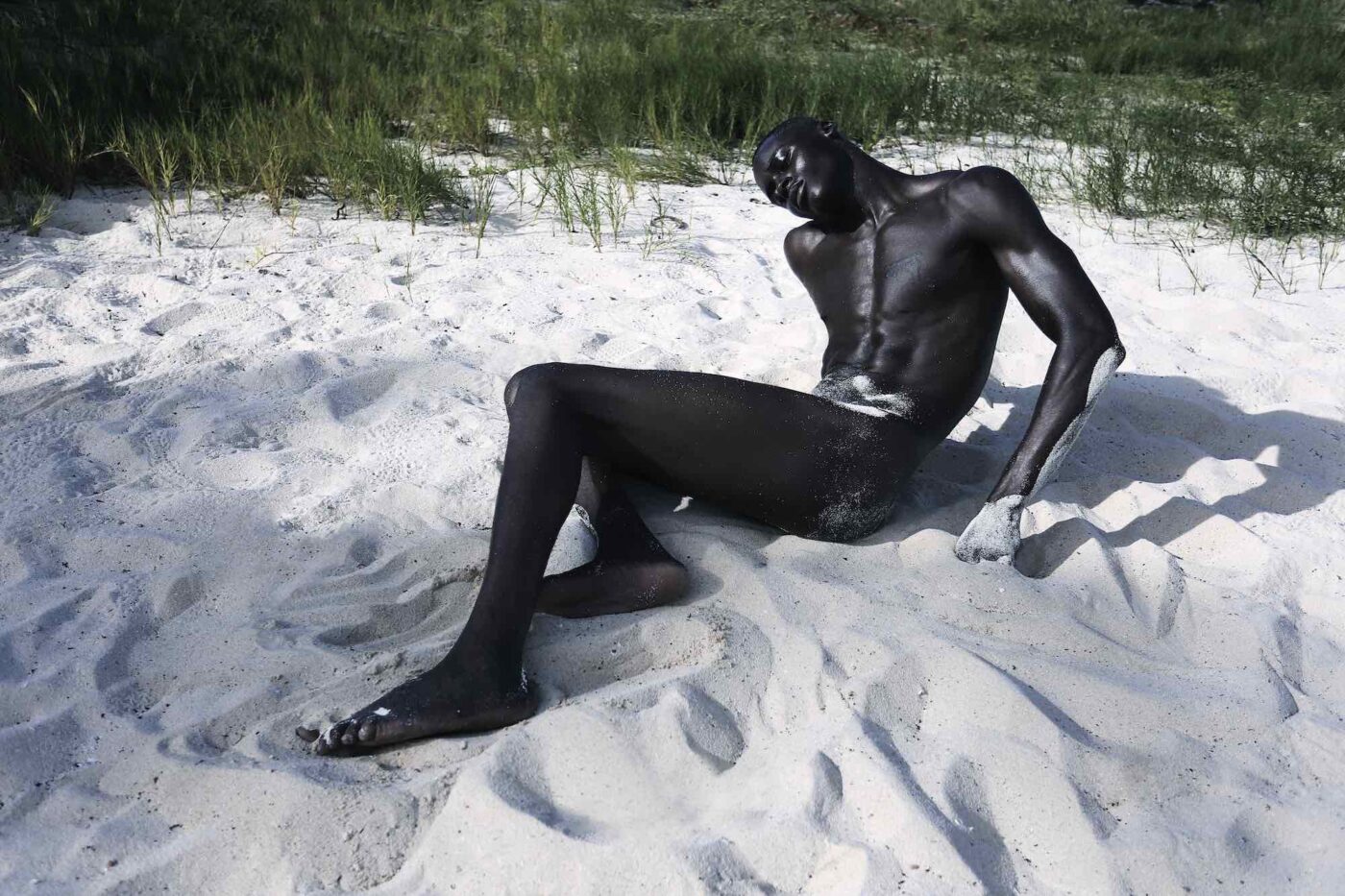

When Playgirl resumed production in early 2022, it faced a dilemma as old as the magazine itself: how to explore sexuality and eroticism from a female perspective? While a number of women have famously contributed to the glossy over the years, including Annie Leibovitz and Brigitte Lacombe and Silvia Pecota and Suze Randall, the majority of Playgirl’s nudes were photographed and art-directed by men (shocking?): David Meyer and Norbert Jobst in the 70s, Greg Gorman in the 80s, then David Vance, Douglas Cloutier, Richard Armas, Dean Keefer and Greg Weiner… “Why wasn’t your Man of the Month photographed by a woman?”, Playgirl is asked all too often. “Women doing this production would be preferred TBH”. They would be, but the female artists we talk to -photographers and videographers- aren’t interested and when they are, they won’t take the plunge. Why is that? Is it prudery? Yet historian Kenneth Clark famously distinguishes between the naked and the nude: “the word ‘nude’ carries no uncomfortable overtone”, he explains in The Nude. A Study in Ideal Form. “In the greatest age of painting, the nude inspired the greatest works”. Is it the stigma of a genre (and a publication) long owned by men? The alleged dangers of commercial exploitation and objectification? Perhaps. Then again, are we being held hostage to our prejudices? Will Playgirl ever break new ground and challenge old constructs, if women keep balking? How else can it find its identity and its voice?

Hoping to find an answer or two, I visited the NUDE exhibit at Fotografiska, the new Contemporary Museum of Photography, Art & Culture in Berlin. Aptly subtitled “The Naked Body in Contemporary Photography”, the exhibit showcases the works of 30 female artists, all turning “the comfortable categories of male and female on their heads”, Frances Borzello writes in the 208-page catalogue, and considering “alternative representations of the male (…) They suggest alternative models for the dominance of the ideal body and classic beauty in the media. They explore the nature of female desire, women desiring rather than being the objects of male desire.”

“Sum of Its Parts,” 2019, © Brooke DiDonato from the collection ‘Rhyme or Reason.’

How’s the nude as seen/reimagined/unchained by these women? Their works vary greatly in styles, themes, techniques, media, perspectives. “From documentary photography through surrealism”, Borzello continues. “They borrow, too, from pornography and advertising” (see Arvida Byström’s Cherry on Top and Joanne Leah’s Untitled Works). I find myself drawn to Julia SH’s Studio Practice series and its ‘unconventional’, Botero-esque female forms; intrigued by Evelyn Bencicova’s Ecce Homo series and its landscapes of men and women piled onto each other; obsessed with Brooke DiDonato’s Rhyme or Reason series and its contorted/distorted bodies. But never seduced, never aroused. I wonder with Clark: can a nude ever “fail to arouse in the spectator some vestige of erotic feeling”?

In her foreword, Pauline Benthede writes: “No longer is the (female) nude limited to the ideas of beauty and voyeuristic pleasure of the (male) viewer; it is a canvas for self-expression on which the artist is in power to paint whatever she desires”. And so did these 30 artists with their innovative interpretations, exploring the relationship between the viewer’s gaze and the viewed, questioning yesterday’s canons, stereotypes and taboos, freeing the unclothed body from the shackles of its idolized perfection. Can they boldly reinvent the rules of a Playgirl pictorial? Yes, and in so many exciting, revelatory ways. Will they? These women have reimagined the nude and will keep redefining it, but on their own terms, as “a canvas for self-expression”. Never as a captive of the spectators’ desires and their (our) pleasure. Never, so it seems, as a canvas for eroticism. And there’s the rub for the “first magazine for women to focus on men”.

“Tom, 20.5km Away,” 2017, © Yushi Li