It could be said that 2024 was a banner year in Hollywood for women over 50, from Nicole Kidman’s overdue sexual awakening in Babygirl to Demi Moore’s gory quest for eternal youth in The Substance. But Gia Coppola’s The Last Showgirl was perhaps the year’s most sincere—and ultimately, most hopeful—cinematic exploration of what it means to age as a woman in our society.

Pamela Anderson brings a lifetime of objectification to the role of veteran Las Vegas dancer Shelly; as such, it wouldn’t be surprising if there were an element of world-weary bitterness to the character—an understandably brittle quality. Instead, Anderson plays Shelly with all the softness of a marabou feather boa, sparkling like a rhinestone headpiece.

At 57, Shelly has been performing in the Razzle Dazzle revue since 1987. It’s the last show of its kind on the Strip—a “dinosaur,” as younger dancer Mary Ann (Brenda Song) puts it. To Shelly, on the other hand, the Razzle Dazzle is the “last descendant of Parisian Lido culture.” When the casino decides to close the show, her very identity is threatened in addition to her livelihood.

As Shelly’s reality frays and crumbles around her over the course of the show’s final days, she faces her future with a mixture of disbelief, panic, and occasional bursts of optimism. Surely, she should have seen this coming—but whether out of denial or naiveté, it seems she thought the Razzle Dazzle would go on forever, and her with it. Shelly is clearly someone who clings to the past: Not only does she still have a landline, but a phone with a cord; she listens to music on a Walkman and wears acid-washed denim. But it’s not that she’s looking backwards, exactly. She simply chooses to exist in a time and place that make sense to her. As she explains it, “Las Vegas used to treat [showgirls] like movie stars…we were ambassadors for style and grace.” Shelly is an artist. The Razzle Dazzle is her vocation—a “spectacle with dancing nudes” but “certainly not a nudie show,” she insists.

The fact that Shelly sees her career as a higher calling is of little comfort to her estranged daughter, Hannah (Billie Lourd), who can’t comprehend why the Razzle Dazzle was “worth missing bedtime for most of [her] childhood” after finally seeing the show for the first time. Still, when Shelly encourages her to follow her dreams of becoming a photographer, Hannah’s sense of validation is palpable. Shelly recognizes that Hannah is an artist. The question is, will Hannah do the same for her mother? Either way, Shelly is done making excuses and apologizing for the choices she made. She knows who she is and what she has to offer. When Razzle Dazzle dancer Jodie (Kiernan Shipka), a 19-year-old runaway, comes to Shelly’s door in the middle of the night in need of comfort and guidance, Shelly turns her away. She might be a mother, but she has no interest in being maternal. At the same time, she can’t escape her nurturing tendencies, particularly in the case of her friend Annette (Jamie Lee Curtis), a cocktail waitress. When Annette admits she’s been living out of her car, Shelly takes her in as a matter of course.

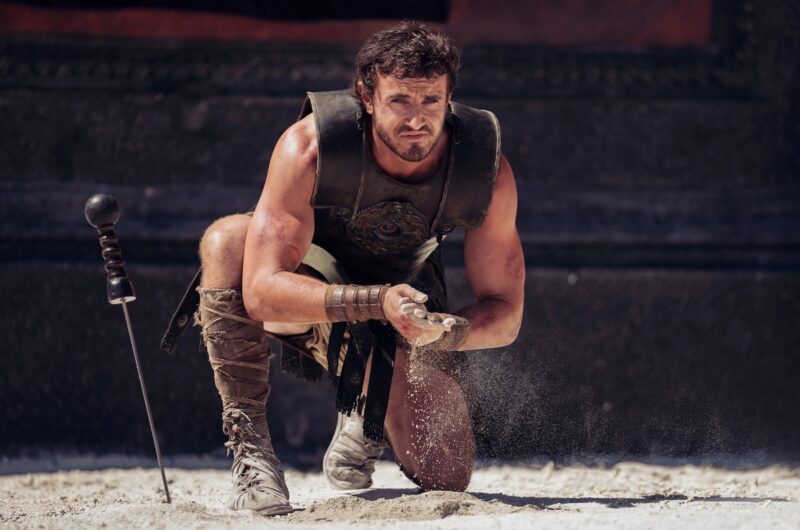

‘The Last Showgirl’ • Photo courtesy Roadside Attractions.

Absentee mother or not, Shelly clearly adores Hannah and desperately wants a relationship with her—and as justified as Hannah might be in her anger, Anderson is so endearingly earnest that it’s hard not to root for a reconciliation. When Shelly’s longtime stage manager (and Hannah’s secret father) Eddie (Dave Bautista) criticizes her parenting, she bristles at the double standard. Eddie—who has apparently done nothing for Hannah since she was born—infuriatingly suggests that Shelly could have taken some other kind of job, something that would have allowed her to be there as a mother. But this completely misses the point: It’s not so much that Shelly wasn’t willing to sacrifice her passion, it’s that she wasn’t able.

“Feeling seen, feeling beautiful, that is powerful. And I can’t imagine my life without it,” she says.

Whether or not she wants to imagine it, the fact is that her time in the spotlight is coming to an end. Shelly is faced with the kind of reckoning that comes for so many women in mid-life, when the world passes judgment on the choices they’ve made and their consequences: Have they been successful in their careers? Did they raise functional, well-adjusted children? Between her life’s work being deemed irrelevant and her strained relationship with her daughter, Shelly could be considered a failure on paper. And in certain scenes, we see her faith begin to falter—when she tears at the costumes backstage, weeping, or when she breaks down after a disastrous audition, lashing out at Mary Ann. Still, Shelly is somehow too pure of heart to believe the worst of herself, a quality Anderson portrays with a stunning authenticity.

The ethereal nature of Anderson’s performance is enhanced by the film’s aesthetic. Shot by director of photography Autumn Durald Arkapaw on 16mm, there’s a gentle blur around the edges of every frame that seems to be an extension of the way Shelly looks at life, muting the uglier moments. The color palette is inspired by a sunset sky: shimmering blue sequins, pink lipstick, the flaming orange of Annette’s hair, the golden glow of the stage lights. We feel the evening approaching, casting a shadow on everything Shelly holds dear.

This nightfall theme is echoed in the ill-fated audition scene, when Shelly bravely dances to Pat Benatar’s “Shadows of the Night.” With literal children as her competition, Shelly’s outdated, technically less-than-impressive moves aren’t enough. “What you sold was young and sexy. You aren’t either anymore,” the casting director (Jason Schwartzman) tells her.

It’s the message Shelly has been running from for the entire movie—a harsh certainty every woman is expected to accept about themselves at some point or another, as an inevitability. But Shelly refuses to listen: “I’m 57 and I’m beautiful, you son of a bitch!”

If feeling beautiful is powerful, then that power is in Shelly’s hands—no matter where her next act takes her.