Understanding movies like The Blue Lagoon involves three time periods: the time represented in the film (late Victorian); the time the film was made and released (1979 and 1980); and the time in which viewers see the film, initially 1980, which included an unexpected strong gay following, and currently 2025. Blue Lagoon is an adaptation of a 1908 novel by Henry de Vere Stacpoole and it’s related to other films about children raised in nature such as feral child narratives The Wild Child, 1970, and The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, 1974, both of which were also adaptations.

Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes, 1984, an adaptation of the 1912 novel Tarzan of the Apes followed just four years after Blue Lagoon. That novel eerily parallels the basic Blue Lagoon plot. The infant Tarzan is marooned in an African jungle with his parents. both of whom die by the time he is 1 year old. He is raised by an ape and grows into adulthood with no knowledge of being human.

Something was in the air regarding nature vs. culture debates going back to the beginning of the 20th century. And something new was afoot in the late the 20th century not just in cinema but in reality: the sexual revolution, feminism, and the gay rights movement, and such milestone cultural events as Woodstock in 1969 and Playgirl magazine, 1973.

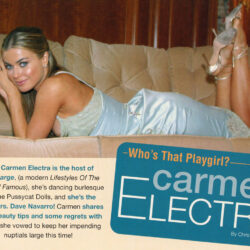

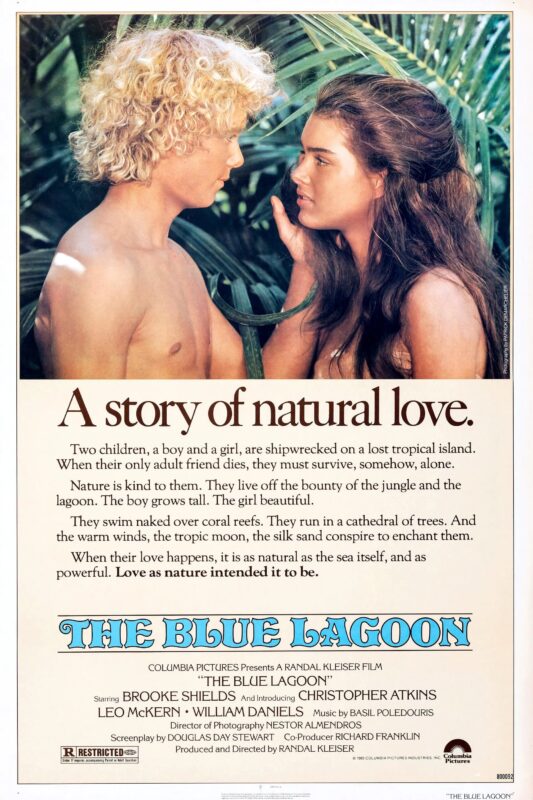

‘The Blue Lagoon’

Casting is another important historical context for understanding Blue Lagoon. Casting Christopher Atkins as the sexualized male in Blue Lagoon, including significant nudity, also has historical significance. In 1980 Richard Gere, age 31, with a mature, well-developed body starred in American Gigolo as a highly sexualized character. The film included a lovemaking scene with unusual male nudity. It was common in Hollywood films to see a nude woman getting out of bed following lovemaking or getting into bed before the lovemaking. American Gigolo reverses this pattern with Gere getting out of bed and standing nude with his penis clearly visible as the woman looks at him. The most striking aspect of this scene is that Gere stands perfectly still. Most male nudity revealing the penis had shown the man in action.

In Blue Lagoon Atkins is highly active in the nude scenes, usually swimming underwater or even carried away by a powerful stream. Blue Lagoon, however, avoids the worst aspect of representing the penis within a common but ridiculous dichotomy: big penises intended to be an awesome spectacle of powerful phallic masculinity and small penises as a pathetic, failed masculinity. There is no such awesome spectacle or its alleged collapse in Blue Lagoon.

The spectacle of Gere’s body in American Gigolo is a sign of things to come: the era of the muscle builder physique of Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone. Indeed, in 1984 Atkins played a thrusting male stripper with closeups of his big bulge (A Night in Heaven). In The Terminator, 1984, Schwarzenegger is introduced fully nude, his body crouched in a small, rounded shape which becomes an awesome spectacle when he stands up. Similarly in Demolition Man, 1993, Stallone is introduced with his crouched frozen body, but he quickly arises to stand erect.

The word “erect” indicates the symbolic way these bodies resemble a penis going from small and rounded to straight and erect. These movies don’t show the penis, but they metaphorically transform the entire male body into a powerful phallic symbol. Indeed, the penis cannot be shown because it would unmask the ludicrous belief that it is a sign of strength and power. Ironically, James Cameron, who directed Terminator, cast a young Leonardo DiCaprio, whose boyish body recalls that of Atkins in Blue Lagoon, as the male lead in Titanic in 1997.

‘The Blue Lagoon’ • Columbia Pictures.

The genre of Blue Lagoon lies at its center. Amazon currently labels the film as “Drama • Cerebral • Compelling • Passionate.” IMDb writes, “Coming of Age, Survival, Teen Drama, Teen Romance, Adventure, Drama, and Romance.” In addition to the above-mentioned feral child narratives about children raised by everything from wolves to apes, the film relates to yet another genre: that of being marooned on an island which began with Robinson Crusoe published in 1719! As the laundry list of genres listed on Amazon and IMDb indicates, it is hard to define the genre of Blue Lagoon. What strikes me however is that the most important one is missing: fantasy.

The core of the film’s fantasy is that children will naturally become normative, romantic, heterosexual, monogamous, married beings regardless of the circumstances in which they grow up. But each of the terms mentioned above can only be understood within culture, they do not arise in a state of nature. Blue Lagoon assumes that young children can somehow internalize all this from looking at a few photographic images on board the ship before they are marooned, even though the film dwells on the fact that they do not know what puberty, menstruation, masturbation, intercourse, and pregnancy are, nor where babies come from!

Consider the cultural icons of Tarzan and Jane. The moment Tarzan lays eyes on Jane, he desires her sexually and romantically. The racial implications are deeply disturbing since he was surrounded by tribal women throughout his life, but because they were not white, they had no impact upon him. Blue Lagoon was advertised upon release as “A story of natural love.” But outside fantasy, there is no such thing. Fantasies should be treated just like any genre. It is a mistake to dismiss fantasy because it is not like reality; we should bring the same critical thinking to fantasies that, for example, we bring to Westerns. Such critical thinking does not dismiss fantasies but, rather, expands our understanding of them.

Nestor Almendros’s cinematography in Blue Lagoon is stunningly beautiful. And the sexual fantasy has some beautiful components to it. Such an explicit adaptation could probably not even be made in America currently. The film celebrates sexuality and the body which is now once again under censorious attack. Even the images of the nude male baby would now be considered by many to be offensive and abusive.

But as with casting and body types, cinema is constantly changing as are the times in which the films are made. After a decade of body building stars, who would have guessed that Titanic, then the biggest box-office film of all time, would star an actor who resembles Christopher Atkins much more than Schwarzenegger or Stallone? Film history does not simply progress to newer and better things; it changes in complex and unpredictable ways. We cannot now imagine how viewers might react to the film in 2040.

Peter Lehman is Professor Emeritus in the Film and Media Studies Program at Arizona State University.