The pilot of Minx, the television series about a fictional feminist porn magazine in 1970s Los Angeles, features a penis montage. About twenty minutes into the episode, titled “Not like a shvantz right in the face” (I personally kvelled), Minx staffers, searching for their first construction worker-inspired centerfold, examine penis after penis after penis. The penises range in size, shape, and color, flopping about in an office in the San Fernando Valley as a newly minted magazine editor, Joyce (Ophelia Lovibond), fans herself with a copy of The Diary of Anaïs Nin. Minx announced itself with a clever, fun spin on the classic casting couch scenario, in which men leer and women tremble.

Showrunner Ellen Rapoport looked at countless old issues of magazines like Viva and, of course, Playgirl, where she saw a construction worker editorial. “There was an article that asked, ‘what do you do if you get whistled at?’” she told Playgirl in a January interview. “And it’s like, ‘whistle back, ladies.’”

That sort of wink is a trademark on Minx, which chronicles the unlikely partnership of feminist editor Joyce and hustling pornographer Doug (New Girl’s Jake Johnson). “The elevator pitch was that it was about a highly educated feminist who has to basically team up with a low-rent pornographer in order to make her feminist magazine dreams come true,” said Rapoport. “It sounded like a comic nightmare.”

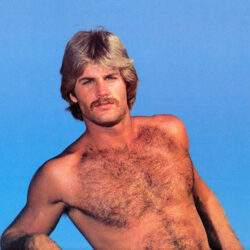

Still from ‘Minx’ • courtesy of Starz.

Rapoport began formulating the idea for Minx after reading oral histories of Playgirl and Viva (she’s collected countless vintage copies, distributing them to the show’s writers, actors, and crew—Johnson’s daughters even got their hands on them). Despite the “cuckoo astrology diet pill and boob enhancer ads,” Rapoport was struck by how current the magazines felt. “We were a very threatening magazine for men,” Ira Ritter, a former president and publisher for the magazine, told Esquire. If you came home and found your wife reading Playgirl, it would be, “You don’t love me anymore?” The newsstands were controlled by men. Jerry Falwell wanted this magazine off the newsstands. We were put in the back rack in 7-Eleven.”

There were stories about women’s health, covering abortions and breast cancer, along with portrayals of the PLAYGIRL herself as a libertine, or a feminist rising up with other women, or a dutiful wife, or all of the above. “Its editors’ letters were like, ‘Well, I like to fuck my husband, and then let me tell you about this horrible story of discrimination,’” said Rapoport.

Minx is indeed feminist, but never pedagogic. Joyce has strong opinions—she can also be screechy and uptight, a human character for a fully-realized world (Rapoport used the character as a Trojan horse to convey her own experiences in the entertainment industry). Doug may be a pornographer—but his care lies mainly with his own bottom line, not with sexual exploitation (“It was important to me that he not be sleeping with the model, and that it felt like he didn’t care if it was boob, or if it was a dick,” she explained. “If it could make him a dollar, he was like, great.”)

“Around when I was pitching the show, I was invited to a ‘cancellation party’ for men, like let’s cancel all men,” she continued. “And I said, ‘I don’t want to cancel all men.’ I don’t know what’s happening. It feels like the discourse now on everything, not just feminism, continues to be people screaming at each other on social media and taking some crazy stand, with no room for shades of gray or questions or anything like that. So I just wanted to step very far away from that. I guess another way to say that is I also wanted men to watch the show and like it and appreciate it.

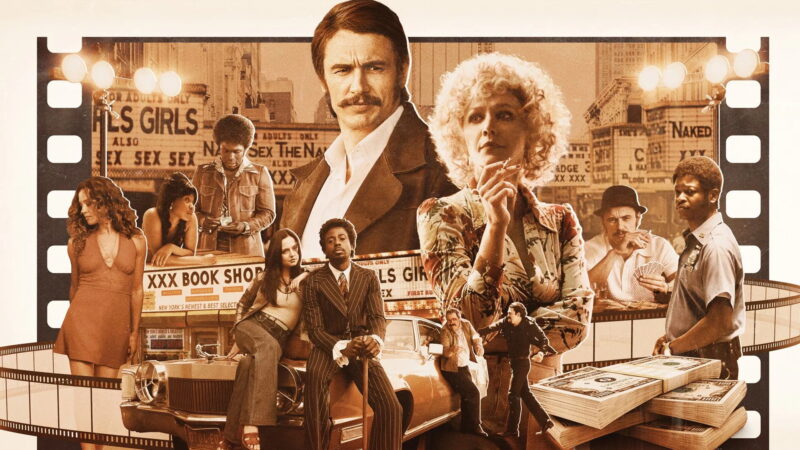

Still from ‘Minx’ • courtesy of Starz.

She succeeded. Minx is feminist both in form and content; Rapoport, who has a background in corporate law aptly portrays Joyce’s frustrations, and imperfect successes, as a woman attempting to rise in a man’s world, and features numerous female perspectives along with using a largely female staff (female directors, writers, photographers, cinematographers). The nudity all comes with purposeful intent and messaging, designed to be witty, move the plot forward, and reveal something about women’s lives.

“In the pilot, the main character is cat-called by construction workers, and then flips it on them,” Rapoport said. “So it’s a nude male construction worker.”

As Doug himself says, “you gotta hide the medicine.” Playgirl itself hid the medicine, with sexy editorials and cover lines focusing on the “compulsions of the promiscuous woman” while publishing serious work from writers like Raymond Carver and Joyce Carol Oates (the old adage may be joking that you read Playboy for the articles, but the articles really were excellent). And Minx succeeds above all, as it should, as comic entertainment. Minx stands out with its sunny tone, bringing light to what’s ordinarily portrayed as seedy. Even the look of the show is bright and cheerful—Rapoport said that season two, after the magazine takes off, is meant to look “nouveau riche,” jokingly comparing it to her own house.

“Everyone was just comfortable,” says Rapoport. “They ended up having fun on nude shoots. It was just a playful kind of set. And there actually were a lot of pulp magazines at the time in the seventies and sixties coming out of the Valley that were kind of cheekier and more playful. And the most boring version of this show, I think, would’ve had a gross porn world. We’ve seen that a million times.”

But doing something different comes with a price. Minx debuted on Max in March of 2022, and was canceled during a flurry of cost-cutting measures while in production for season two. The show was then rescued by Starz, which aired the second season—and then proceeded to cancel it in January 2024, before a third season could begin filming. Rapoport, now working on a new show, has a rare distinction among talented showrunners: she helmed a critically-praised program that was canceled not just once, but twice.

“I think making a TV show is like buying a puppy,” she said. “It has a built-in tragedy attached to it. It’s always going to die before you, unless something goes terribly wrong. It’s unfortunate. I think that the writer’s strike didn’t help. Changing networks didn’t help. But at the end of the day, we got to make two seasons of a show I’m really proud of.”