“The Female Gaze” has taken on nebulous connotations, particularly in the last few years, with TikTok vernacular such as “written by a woman” expanding the term beyond film theory—applying it to celebrities, boyfriends, and even interior design, professing to describe (with questionable accuracy) attributes that appeal to women at large. In a more grounded sense, the term exists as an antithesis or counterpart to “The Male Gaze,” a term coined by feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey to explain, in short, the visual and contextual objectification of women on screen. But this definition-in-opposition still feels shaky—does the Female Gaze encompass any and every work of film made by a woman? Must it consciously take a feminist stance in dialogue with traditional masculine ways of representing and viewing the world? Does gender really play such a substantial role in our voices as creatives?

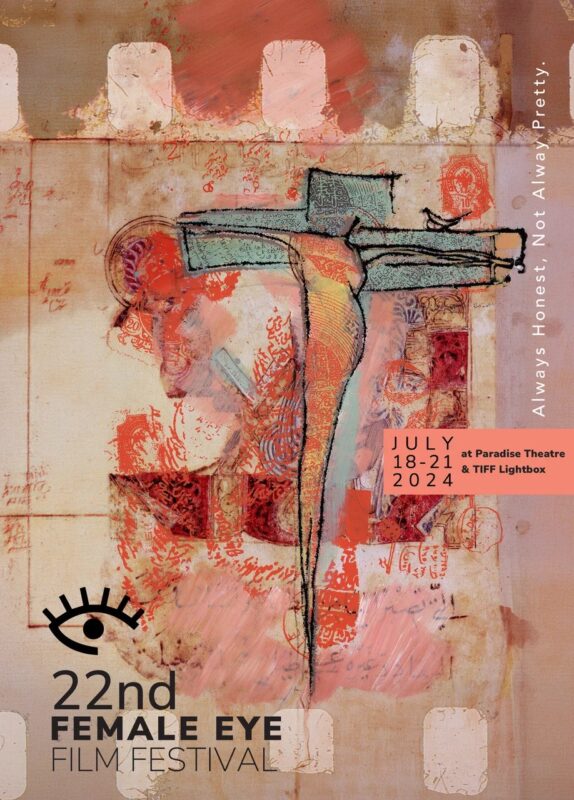

These questions were on my mind when I attended the 22nd Female Eye Film Festival this July. Held annually at Toronto’s TIFF Lightbox Theater, the weekend-long festival explores the nuances of the Female Gaze without aiming to pin down a precise definition, showcasing an admirably broad array of perspectives throughout 65 shorts and 12 feature films, all directed by women. In my time at the festival, a few consistent throughlines stood out as the most pressing themes in the minds of women filmmakers of the moment.

Though women have been integral to film history since the inception of the art form, we have long played the primary role of objet d’art, reduced on-screen to ornaments or arm candy, bodies to be admired but not understood. As such, it’s no wonder that so many of the films screened at FEFF dealt in body horror, whether through overt genre filmmaking or in the more tangibly relatable essence of the term: the everyday horror of existing in a body that the world has an opinion on. Shorts like Cold (Liz Whitmere) and TOOTH (Jillian Corsie) make tangible the nightmarish ordeal of your body deteriorating or attacking you from within, while films like Rebelled/Rebeladas (Andrea Gautier and Tabatta Salinas) and Hemorrhage (Ella Lentini) address the social and physical danger inherent to the female body in a political climate that views our safety as, at best, an afterthought. Several films also grappled with the all-consuming pain of being perceived in an environment that incentivizes pristine images both online and in life, with many grappling with plastic surgery, social media self-mythologizing, and the capitalistic pressure to reduce one’s identity to the ability to sell and produce.

22nd Female Eye Film Festival.

The only thing more frightening than body trouble may be discord within one’s own mind, as amplified by a series of films orbiting the theme of mental health. Admittedly, mental illness has become increasingly destigmatized in recent years, but it can still be a touchy topic, especially when the face of many diagnoses remains largely young, white, and male. Such clinical stereotypes are turned on their head by several films screened at the FEFF, including White Noise (Tamara Scherbak), 3 EASY STEPS (Paige Henderson), and Just Hear Me Out (Malgorzata Imielska), while other projects like & Other Concerns (Sabina Olivia Lambert) and Statu Quo Chouchou (Juliette Poitras) posit that mental unrest spans beyond brain chemistry, and can emerge from the toil of womanhood itself—the psychological tug-of-war born out of the contradictory expectations placed on women and girls. Genre films also proliferated the FEFF, acting as allegorical simulacra for the social and political issues that dominate our lives. Horror-adjacent dramatic features Banned (Reem Morsi) and The Dogs (Valerie Buhagiar) weave in elements of genre filmmaking to amplify the creeping dread of increased hostility coming from outside forces, whether supernatural, dystopian, or terrifyingly real.

Fascinatingly, quite a few films utilized animation as a tool for interior worldbuilding, whether to construct a personal reality entirely untainted by the eyes of outsiders—Northened (Una Di Gallo), The Shadow of Dawn (Olga Stalav), Two One Two (Shira Avni)—or to illustrate a unique way of thinking that defies the tangible landscape around us—The Callback (Kara Herold). The affecting documentary Three (Extra) Ordinary Women (Cionin Lorenzo and Pearlette Ramos) employs animated sequences to delve into a period of life now lost to time, lending gravity to stories often overlooked—of children failed by the adults in their lives, by their governments, by a socioeconomic system built to keep them down.

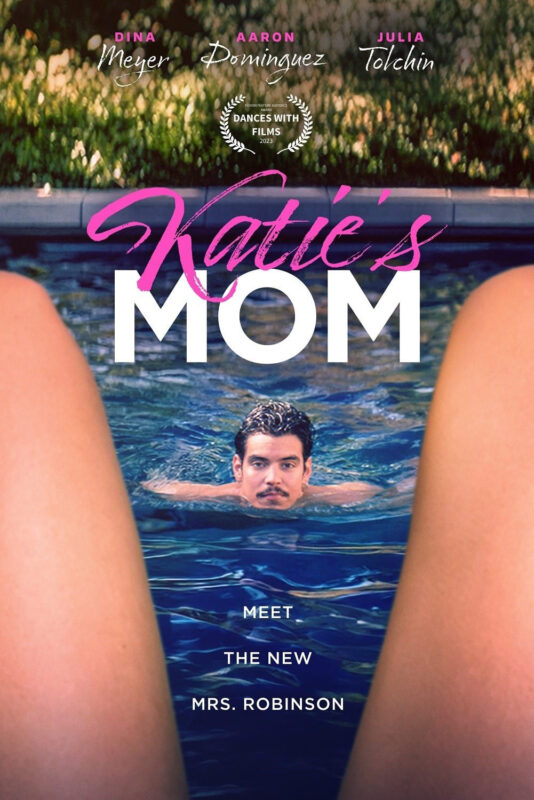

In a refreshing subversion of Hollywood tradition, quite a few of the films showcased at the FEFF featured older women and themes of aging. The disdain for older women in the entertainment industry mirrors the treatment they receive in life: any meagre social capital awarded to younger people for vitality and desirability is revoked, and aging women are relegated to supporting roles, considered relevant only in relation to others. This feeling of cultural invisibility is actively combatted in many of these films, whether through the centering of an older woman protagonist or in more biting commentary, as in the experimental short Potato (Birgitta Liljedahl) in which the Swedish government replaces struggling mothers with glamorous younger models. These movies range in their approach, from the raunchy, MILF-y fun of Katie’s Mom (Tyrrell Shaffner) to the haunting meditation on agency and elder abuse in Age of Consent (Katherine Gauthier and Ben Sanders), but each shines a spotlight on a vital demographic of our community that has long been left in the shadows.

The definition of the Female Gaze is still in flux, as boundless as gender itself. Women, needless to say, are not a monolith, and our voices and visions can’t be distilled to a single filmic style. This is Female Eye Film Festival’s greatest strength—cultivating an interactive platform for women filmmakers to explore the bounds of identity and creativity, broadening the horizons of the canon.

‘Katie’s Mom’