Her career took off in the 1970s as a member of the no-boundaries performance art group COUM Transmissions and co-founder of the groundbreakingly influential band Throbbing Gristle. After leaving Throbbing Gristle, she formed the electronic duo Chris & Cosey with her life partner, Chris Carter. While performing and pioneering the industrial music genre, Cosey also engaged in stripping and worked as an artist in the sex industry. She created collages from adult magazines before considering featuring photographs of herself as the subject. This led her to begin modeling for sex magazines and adult films as part of her art practice.

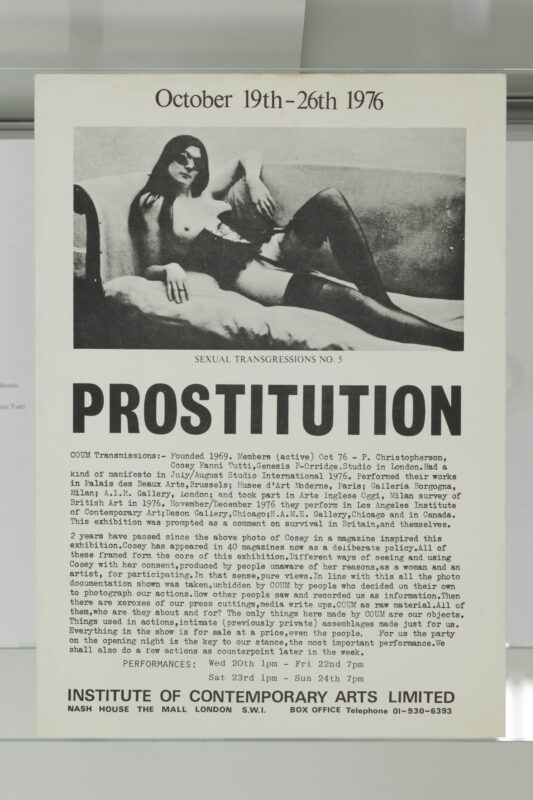

Cosey’s controversial work has drawn attention from various authorities, including the police, tabloid media, the British government, and the art establishment itself. In 1976, during the infamous Prostitution exhibition at London’s landmark Institute of Contemporary Art, she caused a scandal worthy of front-page news when conservative MP Nicholas Fairbairn declared her, Throbbing Gristle, and COUM Transmissions as “the wreckers of civilization.” Over the past 50 years, Cosey has released numerous albums with her various music projects and published two autobiographical books, Art Sex Music and Re-Sisters. Both books delve into the challenges faced by women making subversive works and the backlash associated with doing so. I sat down with her to discuss her life’s work, her new solo album and one-person exhibition in NYC, touching on the porn magazine industry of the UK in the ‘70s and thoughts on the modern-day sex industry.

Your work has often been seen as breaking boundaries. Do you have an impulse that fuels a need to be transgressive?

I didn’t really think of it as in like, right, I’m going to be transgressive. I still don’t think whatever I do is transgressive. I suppose I’m just expressing myself in the way that I feel I need to. And for some reason that has been determined as transgressive, I don’t know why. But I’m just being honest and getting out there and letting people know how I feel in different mediums: music, photography, art, writing. I’ve never done anything for shock value. Not at all. I think that’s quite an empty gesture, to be honest—when anyone could think, what can I do to shock people?

COUM Transmissions ‘Prostitution’ exhibition flyer • courtesy Maxwell Graham Gallery.

Your work has a cheeky humor, evident in the logos and names of COUM Transmissions and Throbbing Gristle. Are there topics too serious for jokes?

I don’t know, I have got a sense of humor. It’s always there. I think I’m more having fun than I am being serious. But there’s an underlying seriousness about my work for sure. I mean, I’m not laughing at my life where it’s been difficult or topics that are difficult or not usually talked about. I’m not poking fun at that at all. You know, that is serious. But underlying all that, yeah, there’s irony.

In Art Sex Music, you candidly wrote about your life story, using old emails and diary entries. Is that how this autobiographical memoir came to be?

Yeah, yeah. I have a few people that I’ve written to since my mail art days, who have gone from mail art to email. I’m always writing and swapping ideas. So that’s become like my diary in some ways. And then I have on my desktop a folder that’s got diary entries for any particular year.

You exposed yourself and used your nude bits to subvert the narrative and reclaim the power from the exploitation of male photographers and adult magazines. Were they aware of your intentions, and if so, what was your relationship with them?

There were just a few of them that kind of understood where I was coming from, but not completely… The guy I mentioned in Art Sex Music, Michel [from Tabor Publications, “a small but prolific mid-market sex-magazine publisher”], who I had a relationship with. The more interesting guys were the ones that were okay with me doing what I did and finding out why I did it. He’d been a mercenary and he was very interested and into magic and stuff, so we had a kind of connection there other than the modeling.

Also, the [American photographer, Joseph] Szabo, because he knew Ginsberg and people back in the day, and so we had a lot to talk about. He was the one that I had the most collaborative modeling experience with. But that was kind of fetishistic as well, because he used to lay out all the makeup on this mantle for me. He’d have this idea of what I’d look like, and he’d ask me to bring certain clothes with me. I remember with Szabo, I took what I call my leather boy shorts with me, that I got from a gay shop in Wardour Street in London. The only shop that probably would have sold them and with a zip that goes all the way around, of course, for ease of access. They were really special to me. But Szabo was brilliant in that respect: it was a real collaborative thing. And obviously a thing of trust as well because he had me tied up at one point and I remember him coming and sort of looming over me to adjust my hair or something, and he had this dirty laugh. I remember it, and he said, “you know I could do anything now, don’t you, Cosey?” And I said, “of course I do but I know you wouldn’t, Szabo.” (laughs) He was a lovely guy and an interesting person as well.

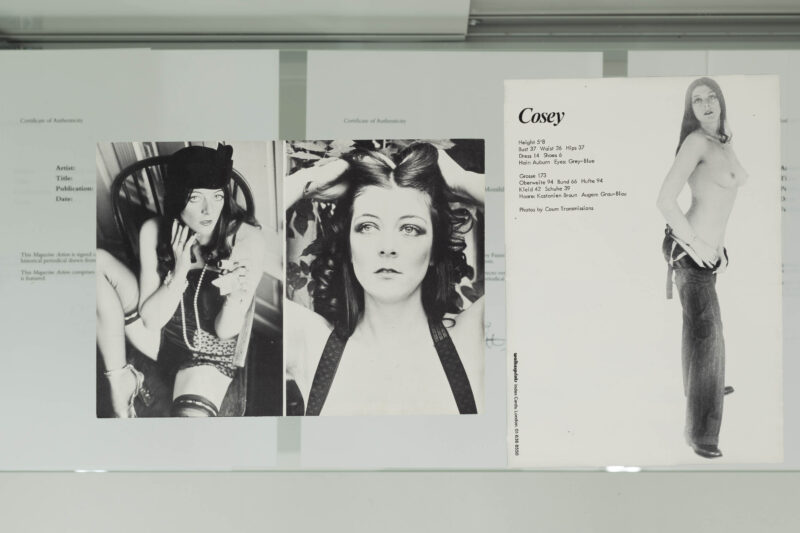

Courtesy Maxwell Graham Gallery.

And the only other person was [British businessman and former pornographer] David Sullivan who ended up owning a TV station and a football club. He was questioned about how he made his money in the sex industry, and he just said: “all I think is, I made a lot of people very happy.” Which is true.

So, there were those three people that stand out that were quite supportive of me, really. And the rest of them, well, I don’t think I spoke to any of them again. But having said that recently, since the works have been exhibited, one of the magazines did a catch up, I think it was “40 years later” and included some pictures of me way back from the ’70s and then put some in of me where I am now, which was fantastic. I thought that’s a really nice thing to do, you know, where was she then and where is she now? Different editor, of course.

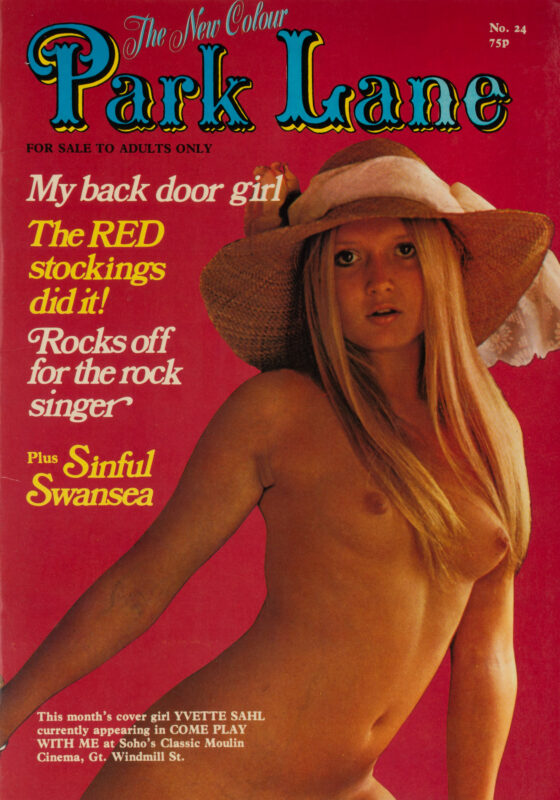

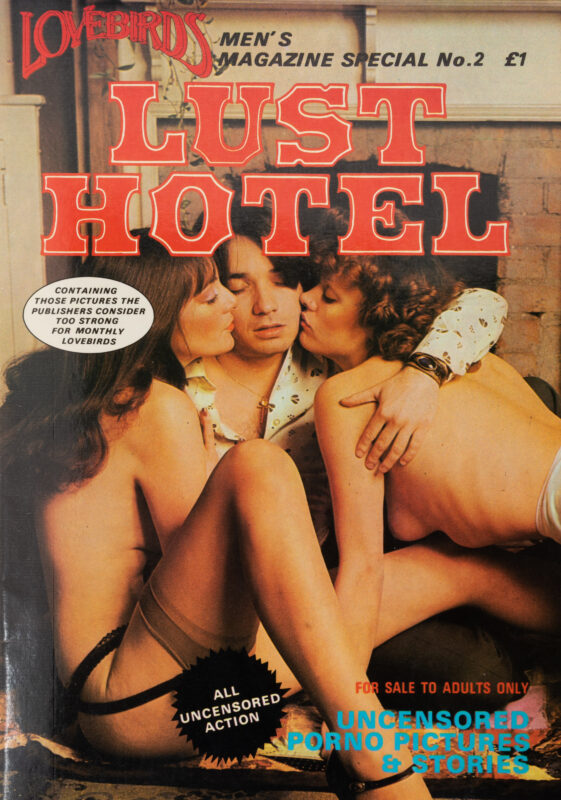

What were some of the names of the magazines? Are these the works in the Magazine Actions exhibit up now?

Yeah, there was Pussy Cat, which was a rubber magazine. That was an interesting experience. And there’s obviously Men Only, Piccadilly International, and Penthouse—I was in Penthouse a couple of times, just briefly. For American ones? Partner. What are the ones here? Oh, gosh, there’s so many of them. Experience. Exposure. Climax. Typical names of magazines that you would expect from the ‘70s like that, you know.

I’ve never explored that porn mag world of the ‘70s, kind of at the beginning of it all…

It was a different world, totally different. Wild, very underground.

Part of the ‘Magazine Actions’ exhibit • courtesy Maxwell Graham Gallery.

You worked with Sasha Gray on Throbbing Gristle’s 2012 cover of Nico’s album Desertshore. Are there other contemporary women blurring the lines between art and pornography? How has the internet changed the ability to reconstruct and challenge narratives as you did in the ‘70s?

I think it’s changed ever such a lot now. Like I said, because it was underground back in the 70s. It was illegal here to do it. Certain things are still now illegal, I’m sure, but I mean—I’ve yet to see what is! Going by the internet, you know, it’s really extreme sometimes. But I think for women, there’s more of their own agency now than there was back then. They have their own film companies, they do their own thing, which is absolutely brilliant. But when I spoke to Sasha about it, and when I saw a couple of documentaries as well about it, I thought it’s still the same kind of manipulation going on. That hasn’t changed, you know, it really hasn’t. And I can watch those documentaries.

Documentaries about the adult industry?

Yeah, there were a couple. Annabel Chong—Sex: The Annabel Chong Story. I can’t remember the other one. But there’s all those ones now where the girls are screwing so many hundreds of thousand guys and that kind of stuff. I don’t get that.

I think the joke’s on them in the end—they’ll hold the world record for most sex partners but at what cost?

That’s not sex to me. It’s just clinical: in, out, next. You know, it’s a weird thing to do. It’s not fucking. It’s not sex. It’s not sensual, nothing. I mean, at least when I did it, there was an attempt for it to make the viewer turned on and the actual action be in some way sexual and stimulating in that respect. I don’t access porn nowadays, so I can’t really comment on it. I’ve been there and done that.

Were the photographs explicit or was it just you solo like in a Playboy spread, or implied…?

It’s simulated in magazines. The films weren’t simulated, not all the films. And I did body doubling as well for some films where they’d have to have sex scenes in them.

Part of the ‘Magazine Actions’ exhibition • courtesy Maxwell Graham Gallery.

What are your thoughts on pornography as a commodity today? We discussed OnlyFans giving models autonomy and the ability to create their content on their terms without a “pimp” in the equation….

I think there probably still are [pimps] in some circumstances. Yeah, I think there are. The sex trade as such is opposed to people, like you said, autonomous people. That for me is great. That gives you a sense of freedom to do what you want and explore your sexuality without any coercing.

Audiences and critics have misunderstood your work. Do you ever wonder how they could have gotten it so wrong? Any regrets or things you think you could have done differently?

No. I did it the way I wanted to do it, how they received it is up to them. I don’t have any regrets like that because I think what happens after the event feeds into what comes next. And that can either be like a good thing or a bad thing, but down the line, everything sort of turns around and creates something of interest later on in life. I don’t have any regrets whatsoever, because where I am now, I wouldn’t be here, had those things never taken place.

Do you get a sense of validation from media and press response? Is the feedback part of your drive—to see how people respond?

No, not really. No. I think I’ve always just done it as a sharing thing: self-expression as communication to other people. It’s just a drive I have in myself to create. And if I can share it, I do, and then… I’m open. I’ve always had criticism, so it’s never really bothered me. It’s when people pay me compliments that I have trouble with that. I just suddenly think, hang on, I’m not used to this. Give me criticism and I’ve got something to sort of bite into in a way, whereas I don’t know how to handle compliments.

In your second book, Re-Sisters, you recall an audience member at a reading of Art Sex Music asking: “Did you write this yourself?” Do you see a path for women to break through that notion of inferiority?

Gosh, I wish I had an answer to that. I really do. I know there’s a lot of ghostwriters around for memoirs—for male and female memoirs. Surely, they would have known by reading the book that it wasn’t a ghostwriter. I think they were just aiming at me, someone causing disruption on purpose. But it didn’t go down well. The crowd was just like, “Oh, God, for the fuck’s sake.” Neanderthal there in the back row. But yeah, that still goes on, that whole thing of women being inferior in some way. I still don’t get it. Even as a child, I never felt like that.

You mentioned that there is a film project called Art Sex Music being made about you and your life as like a biopic. Is that still in production?

It’s not a biopic anymore. That didn’t work out. I’m working on a more of a creative documentary with Caroline Catz, who is directing it, and Andy Starke producing, from Anti-Worlds production company. They’re the ones that did the Delia Derbyshire film that I did the soundtrack for. We’re filming this week. So that’s really exciting. Hopefully we’ll have an edit by the end of the year.

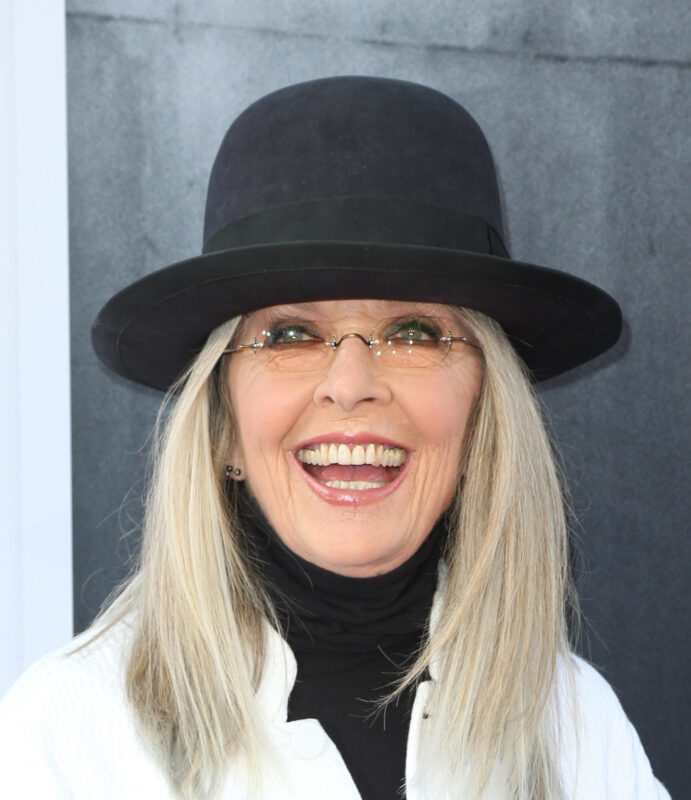

Cosey Fanni Tutti photographed by Chris Carter.

You were part of an exhibition at the Tate Britain called Women in Revolt! featuring feminist art by over 100 women artists and you’ve been on panel discussions with other alt-feminists and the likes of Pussy Riot. Are there any contemporary avant-garde performers you would include, if you were to curate a similar show from the 21st century on?

I don’t know. I think it’s quite sad to say, because that Women In Revolt! exhibition is about collectives of women, usually in London [from 1970-1990]. But there’s a lot of women like me that were working in isolation. Because trying to find another woman that was doing something similar to me, I wouldn’t even—I didn’t even think of trying because I’d been so used to kind of working on my own. And there’s a lot of women still like that, I’m pretty sure, that are just getting on with it. For me, I don’t look out thinking, who can I work with now? The idea of the project that sort of pops up in my mind is the priority and it doesn’t necessarily involve anyone else.

Has your relationship with the provocative changed over time? How do you feel about someone like Madonna, still putting on a leotard and gyrating on stage?

She still does a good show and she’s happy doing it. And surely in life that’s all that matters, isn’t it, that you’re happy? This whole sort of tendency to criticize, particularly women who carry on doing what they love doing: music or art or anything else. Men don’t get the same kind of criticism. And I think that’s wrong. She can do what she wants, you know? And she has.

Yesterday, I saw Shirley Manson on stage with Garbage at the Cruel World Festival in LA. She’s recently talked about aging unapologetically in interviews.

Yeah, it’s true. I mean, it’s up to anybody what they want to do with their body, but I do disagree with plastic surgery, and I don’t like it, trying to halt time and the way you look. It’s prioritizing the outside, not the inside. And the inside is really important, how you feel, because that’s who you’ve got to live with. You know, the person in the mirror when you start tweaking and pinching here, there and everywhere—and it reflects back. And for me I can look in the mirror and I think, yeah, that’s me. Now, I recognize me. Every line in my face has earned its place there. And I’m happy with that.

Let’s talk about your new album, 2t2. Are there any concepts you’re exploring or anything you want to say about your process?

Yeah, 2t2. It’s a continuation of Tutti, which was about my life and 2t2 is as well. It’s a sound exploration and expression of everything I’ve been through over the past five years, really. So much has happened in that time and for a lot of other people around the world, to have to deal with, you know. So that’s what informed the album totally. That’s why it’s kind of in two halves. One’s quite ambient and contemplative. I suppose leaning towards melancholic in a way, but in a very positive way. I didn’t want it to be sad. I just wanted it to recognize sadness and then that was quite a good thing to do, you know? I remember [former Throbbing Gristle bandmate, Peter Christopherson aka] Sleazy at [his life partner, Jhon Balance’s] funeral, he stood up at one point and he said, “I just want to say, please feel free to cry because I know I will. So, everyone just cry, don’t hold it back.” And that was really important. And so everybody did, they just howled. It was a beautiful ceremony. And that’s what I meant about the quieter side of the album is that you shouldn’t hold things like that back. The more rhythmic side of the album is about the joy and the power of resisting things, really, not letting them get you down. And coming out the other side of some very, very dark times. So that’s what the album’s about. It’s a celebration, really.

Do you have any intent to tour this?

No, I don’t perform live anymore. Not now. I think other than performing in the UK, it’s extremely difficult with our equipment as well. Because of Brexit and then because of the new things, visas in the USA. It’s just like too expensive and too unpredictable as to whether you’ll actually get in anywhere. So just studio based now. You get more done.