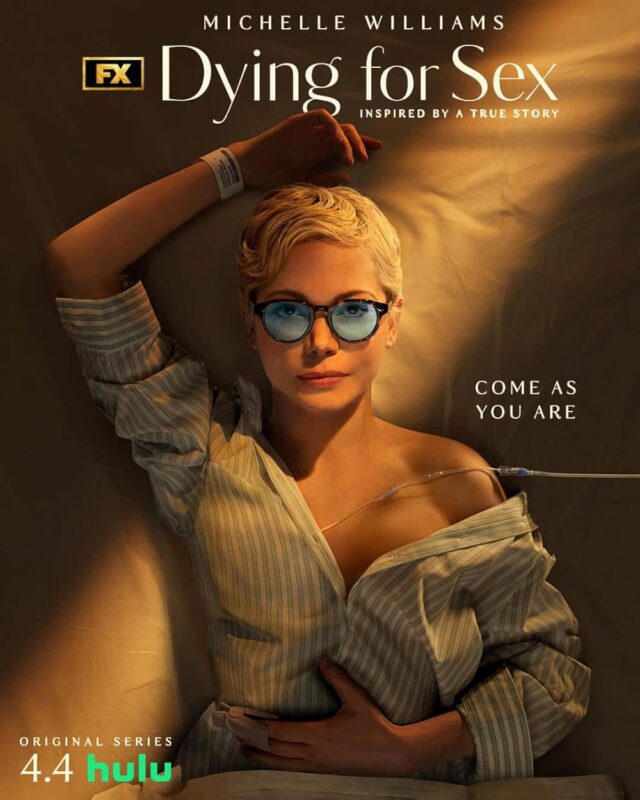

Dying for Sex is a show about many things: Coping with the devastating reality of a fatal illness. The transcendent power of female friendship. Healing a fractured mother-daughter relationship. Breaking free from decades of sexual repression. Flying penis hallucinations. But above all, it’s the story of a woman staring death in the face and defiantly choosing to heal with whatever time she has left.

Based on the 2020 podcast of the same name, the FX series tells the true story of terminal cancer patient Molly Kochan (Michelle Williams). After receiving her diagnosis, Molly is inspired to leave her smug, mealy-mouthed husband, Steve (Jay Duplass), and embark on a quest for sexual self-discovery, aided by her utterly devoted — if unprepared — best friend, Nikki (Jenny Slate).

The journey that follows covers an impressively wide range of emotional territory, from the heartbreakingly profound to the hilariously absurd, sometimes at the same time. Case in point: It’s impossible to choose between laughing and crying when Slate breaks down after Molly admits her cancer is back in the very first episode. (Slate is at her best here, ricocheting from disbelief to sorrow to rage at lightning speed — the stuff of Emmy nominations, to be sure.)

There are infuriating moments, too — many of which come courtesy of Steve. Right out of the gate, he shows the audience exactly what he’s about when he reacts with what seems like relief at the news that Molly’s cancer has returned, all because her illness will grant him a reprieve from fixing the sexual disconnect in their relationship (which he conveniently blames on her first bout with cancer). In the second episode, titled “Masturbation Is Important,” Steve technically comes through for his wife when he pays off a hacker to stop him from blackmailing Molly over a video of her masturbating (the result of a day spent in a hotel room experimenting with a vibrator on a cam site). Unfortunately — and unsurprisingly — Steve immediately cancels out his good deed, telling Molly the photo of her face mid-masturbation session is “disgusting” and insisting he doesn’t want to see her that way.

Dying for Sex • FX.

The whole point for Molly, of course, is that she does want to be seen that way. And what makes Steve’s comment even more hurtful is the way it cuts straight to the deep-seated feelings of self-loathing Molly carries with her as a victim of sexual assault.

Molly’s assault as a child by her mother’s boyfriend is revealed earlier in the TV series than it was in the podcast. As creators Elizabeth Meriweather and Kim Rosenstock told Variety, this restructuring was part of their effort to depict “the decision to heal or work through it, and what that actually looks like.” Her unresolved childhood trauma is why Molly can’t have an orgasm with a partner (an elusive goal which, ostensibly, is at the center of her mortality-fueled sexual exploration). It’s also the reason behind her strained relationship with her mother (Sissy Spacek). But for Molly, the fact that she’s never been able to surrender herself to another human being goes far beyond the sex act. It’s just one more cruel way her body has failed her — and she’s determined to recoup the loss before her corporeal form serves up the ultimate betrayal.

In Episode 3, “Feelings Can Become Amplified,” Molly melts down after breaking her femur while obliging her Neighbor Guy (Rob Delaney) with a swift kick to the crotch (more on that later).

“It’s my stupid, fucked-up, broken body. I hate it. I got cancer twice. I can’t even have normal orgasms from normal sex,” she laments from her hospital bed to Nikki and her social worker, Sonya (Esco Jouléy).

Sonya is quick to disabuse her of the notion that “normal” sex exists, in one of the series’ most oft-quoted monologues (featuring a Sex and the City callout).

“You early millennials are so tragic,” she says. “You know, you think sex is just penetration and orgasms. Why? Because that’s what Samantha said.”

It’s a lightbulb moment for Molly, who quickly learns to embrace the possibilities offered by non-penetrative sex. But her ingrained feelings of shame remain, and she’s still consumed by the desire to feel some semblance of bodily agency.

“I need to be in control,” she says in Episode 4, “Topping Is a Sacred Skill,” and goes on to assume a position of power while engaging in a bit of “penis humiliation” with a good-natured submissive named Hooper.

As Hooper kneels hopefully in front of her, Molly struggles to find her footing.

“What a stupid, stupid penis,” she says, sounding not unlike Martha Stewart chastising one of her kitchen staff in the Martha documentary (“Well, isn’t that a stupid knife?”)

Photo: Sarah Shatz, FX.

But before long, her inner volcano of fury erupts, spewing pent-up rage over her years of feeling like a helpless, damaged creature at the mercy of her abuser, her doctors, her husband, and her disease.

“You’re weak. You’re pathetic,” Molly says, holding Hooper down and covering his face. “I hate you…I hate you,” she says with increasing intensity, as Hooper resorts to his safe word. But Molly keeps going. She doesn’t hear his pleas at first, and she doesn’t see him — instead, she sees herself lying on the floor, still and mute as a corpse.

“It felt like you were thinking about something else there,” Hooper says when Molly finally pulls herself together.

If Hooper (and other submissives Molly encounters) guide her towards a deeper understanding of control and compassion, it’s the aforementioned Neighbor Guy (we never learn his actual name) who truly gives Molly free reign to plumb the depths of her most complicated and conflicted kinks. Initially, Molly can’t stand Neighbor Guy. She’s revolted by the way he eats tacos in the elevator and seems unconcerned with common courtesies — until her contempt turns into an undeniable attraction.

“You’re disgusting,” she tells him, echoing Steve’s earlier condemnation of her own sexuality. But unlike Steve, she doesn’t shrink away from the declaration. She runs towards it. Ultimately, she doesn’t have a choice.

Illness brings with it an inescapable element of disgust. Decay, disease…these are all part of the slow (or fast, in Molly’s case) march to mortality. Without learning how to accept the most unacceptable parts of herself — as a dying woman, as an assault survivor — healing for Molly would be impossible.

In her hospital bed, with Neighbor Guy, Molly’s big moment finally arrives.

“It’s leading up to this moment that Molly has so bravely built herself up for and has opened herself up for and has put out the calling into the universe that she wants this thing,” Williams told Decider. “She may never get it. She may not be able to have the thing that she wants before she passes.”

And yet, she does.

In the final episode of the series, titled “You’re Killing Me, Ernie,” strangely upbeat nurse Amy (Paula Pell) explains that death is simply a “bodily process, like giving birth, or like going to the bathroom, or coughing, having an оrgasm.”

“Your body knows how to die! How cool is that?” Amy says.

Molly at last knows for sure that she can trust her body…even if she can’t control it.