In his book Opera in the Flesh Sam Abel examines ‘sexuality in operatic performance.’ It’s probably no coincidence that an image of famed French soprano Emma Calvé (1858-1942) is seen on the cover as Carmen, the seductive heroine in Georges Bizet’s opera of the same title which premiered 150 years ago in Paris at the Opéra-comique. It caused a scandal and flopped with the family friendly audience of that theater, who didn’t want to see a “nymphomaniac” lead a law-abiding soldier called Don José astray with her hip-swaying dancing and languorous singing. The opening night on 3 March 1875 was a fiasco. Bizet fled to his country estate in Bougival and died there of a heart attack, aged only 36.

The performance rights and royalties went to his glamorous wife Geneviève, later the role model of Marcel Proust’s character Odette de Crécy. She managed to turn Carmen into one of the greatest opera favorites of all time, always landing at the top in any chart of the most popular and most played operas in the world. Because every mezzo soprano wanted to sing the title role: the femme fatale that no one can resist, the free-spirited factory worker from Seville in Southern Spain who smokes cigarettes and gives her love (and body) to whoever she likes, to fulfill her own pleasure, ignoring social conventions. And audiences, in turn, love to watch as Carmen does on stage what so many only dare to fantasize about: grab life by the balls, even accepting death as a consequence. Because, as everyone knows, the opera ends with Don José stabbing the heroine in front of a bull fighting arena, where Carmen’s new love interest – the torero Escamillo – is strutting his stuff. It’s one of the most famous femicides in operatic history.

As Sam Abel writes: ‘Carmen is actually more perverse for refusing sex, not for engaging in an excess of it. She may throw Don José a flower, but that’s all she throws at him. (…) Don José, tired of waiting, decides to go ahead and have sex by himself at her feet, in the orgasmic “Flower Song,” while Carmen listens passively. In the standard operatic sexual discourse of the nineteenth century, Bizet should follow José’s intensely sexual aria with a consummating duet; instead, at the end of his exquisite climax, Carmen responds with “Non, tu ne m’aimes pas!” sung in a flat, frigid monotone. The result is an image of coitus interruptus. Camen gets into trouble not for having too much sex but for not having enough. José kills her because she refuses him sex, not because she gives it to him.’

Well, she may not be shown on stage having sex with José. That would have been impossible in 1875. But in her big musical numbers – the famed ‘Habanera’ sung over a smoldering tango rhythm, her whispered ‘Seguidilla,’ and then her all-shame-abandoned dance ‘Les tringles des sistres tintaient’ – she makes it pretty clear to anyone who will listen what sex with her would be like: wild, no holds barred, an earth-shattering experience. Bizet makes sure that message comes across loud and clear.

In the final showdown between Carmen and Don José the composer also makes clear how desperate José is at the thought of losing Carmen and her affections. Bizet doesn’t take sides, he makes both characters utterly understandable in their positions – she wanting to be free to fuck whoever she wants, him not able to accept that this woman just dumps him when her fancy moves on. In that finale, Bizet pulls all the emotional stops out, musically speaking, and literally floors the audience with overwhelming sounds that grab you by the throat and crack your heart open. We feel empathy for both characters, understand their pain, but also their unstoppable need for liberty and lust. And we understand the incompatibility of both their concepts. Watching Carmen and José fight their final fight is tragic because it resonates with us on so many levels. It’s the essence of love and sexual longing that cannot be neatly put into boxes. Which is why the original Opéra-comique audience reacted so averse: Bizet and his librettists made the neat bourgeois order of the world collapse.

Carmen is described as a ‘gypsy’ and thus as someone living outside the borders of bourgeois society in the libretto, which was written by Geneviève’s cousin Ludovic Halévy. He and Henri Meilhac adapted the 1845 short story by Prosper Mérimée for the stage. Both men had become famous as the librettists of composer Jacques Offenbach (who was also closely linked to Bizet). The operettas of Offenbach were worldwide successes but considered by contemporaries as ‘morally dangerous.’ When Offenbach’s medieval chastity farce Genevieve de Brabant arrived in New York in 1868 the reviewer of the Tribune called it ‘the most revolting mass of filth that has ever been shown on the boards of a respectable place of amusement in this city.’ He continued: ‘Geneviève is not merely indecent, […] it grovels in a low depth, even below decency.’ The singers who performed such indecencies in the United States were paid up to $ 1,200 monthly, in gold, while the average leading actress in the best dramatic theaters were paid $ 50 a week. The performances were pornographic, you could say in today’s parlance. And the operetta theaters, in Paris and elsewhere, were used as a form of brothel, as Émile Zola describes in his 1880 novel Nana.

Meilhac and Halévy come from such a theater world, as does Bizet (whose first show was put on by Offenbach). It’s no wonder that their Parisian contemporaries saw Carmen as a child of that milieu. The core audience of operettas in Paris were the freedom-seeking members of the Jockey Club who thought themselves above the moral restrictions of society because of their wealth and high social standing; they loved to poke fun at the moral restrictions of the average members of society. The women they were after – in theaters, as well as outside – where the Grandes Horizontales of the age, courtesans such as Cora Pearl, Marie Duplessis, La Païva, Valtesse de la Bigne or Hortense Schneider who – like Carmen – decided for themselves who to give their sexual favors to. These women made a business of who they lavished their attention on, often amassing vast fortunes in the process. (Many of them performed in Offenbach’s theaters.)

Courtesan Cora Pearl. Photo: E. Disderi, 1860

One could argue that Meilhac and Halévy used the cigarette-smoking gypsy girl from a factory in Seville as a metaphor for a kind of woman their audience knew so well. In that sense, Carmen is a metaphor for a woman who is shunned by mainstream society for not playing by the rules, for making her own instead, using her body as her capital, just like today’s OnlyFans creators.

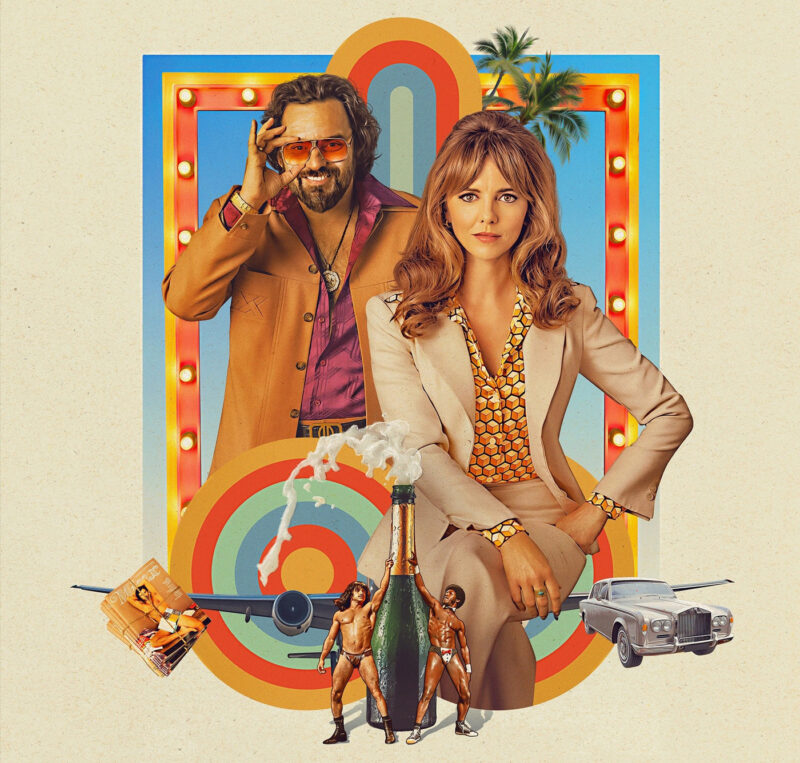

In that way, the character of Carmen is less a ‘racist’ depiction of a supposedly loosely moraled woman from the Sinti and Roman community, as some activists have argued in the recent past. Leading, among other things, to stagings like that of Christian Weise at the Gorki Theatre in Berlin in 2025. Weise wanted to deconstruct the supposedly racist narratives and stop the never-ending femicide cycle in which Carmen has been caught for the past 150 years. He cast Carmen in a gender reverse way, Lindy Larsson was a man in pink Carmen-drag, Via Jikeli a very yellow clothed drag king José. Both stepped out of their roles in the finale to discuss – with the audience – how the story of Carmen might be ‘rescued’ and how Carmen as a woman might finally get ‘justice’ without having to die night after night after night in some staging around the world.

As it turned out, there is no solution. The ending – of these two characters not being able to come together for longer, instead pushing each other away with their contrary needs – will remain forever tragic. And a reminder that the unashamed promiscuity of Carmen vs. José’s longing for security and possession of a partner can never be reconciled. The astonishing thing is that this truth – and its reenactment on the operatic stage with the mesmerizing music of Bizet – has lost nothing of its significance. It remains modern and one of the great riddles of the world. Even 150 years after the premiere of Carmen on that fatal night in March 1875.

One thing worth taking home, as a message, from the Weise production at Gorki Theatre is that one shouldn’t reduce Carmen to a mere folkloristic spectacle with ‘nice’ music everyone can sing along to. Instead, one should take the story seriously. And always reexamine it in the light of our ever-changing society. Because women living their lives – including their sexual lives – according to their own desires and rules are still seen by too many men as a threat. And they are still killed for that. Because some men cannot cope with such anti-patriarchal insubordination.

Carmen – Gorki Theatre. © Ute Langkafel MAIFOTO

The men who created Carmen were aware of this. And many of the woman who have sung (and staged) Carmen since 1875 have embraced the opportunity to highlight such feminist insubordination. Or, as Sam Abel writes: ‘Art does more than hold a mirror up to life, it creates images in which I can play out my own private fantasies.’ Even if the Carmen fantasy of freedom is not for all of us, seeing it acted out on stage is a reminder that it might be worth exploring that side in ourselves, even if only in our minds. Allowing sex to be just sex, whenever and wherever we want to have it, as women and as men. The world doesn’t have to collapse because of it and we don’t have to kill our partner when she or he moves on, as painful as such a loss might be. As Carmen sings in the immortal words of Meilhac and Halévy: “L’amour est un oiseau rebelle / Que nul ne peut apprivoiser / Et c’est bien en vain qu’on l’appelle / S’il lui convient de refuser / Rien n’y fait, menace ou prière …”

It takes a lot of self-confidence and courage to live a life like Carmen. And it remains dangerous, even today, as statistics of femicides show, in the West as well as elsewhere. So, ‘Prends garde à toi!’

Carmen – Gorki Theatre © Ute Langkafel MAIFOTO