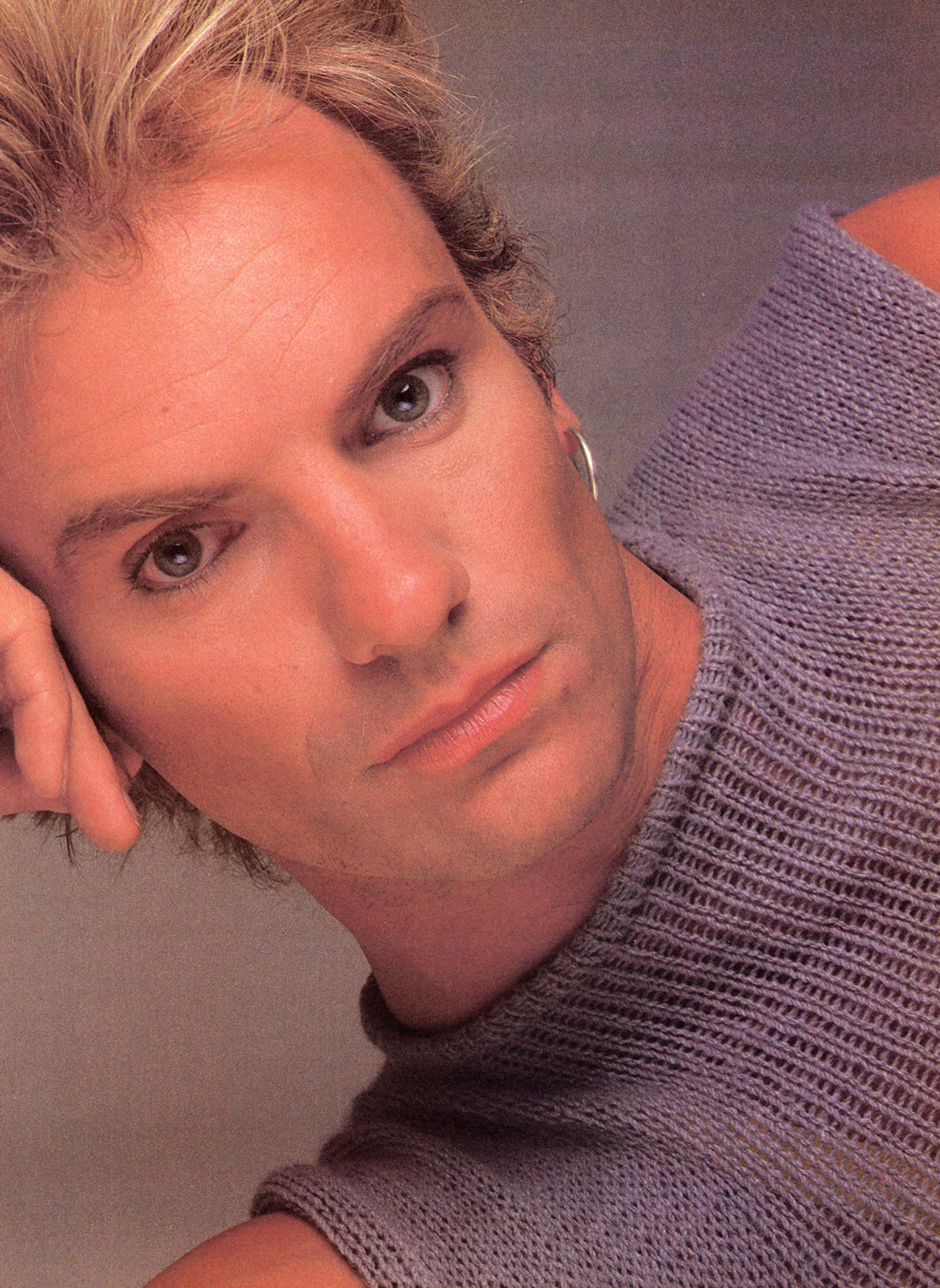

Late Summer 1984, London: I follow the music through the kitchen of Sting’s north London home, and past the billiards room, where I find Sting sitting in a small cubicle. The tiny, closet-like space is crammed with various guitars and basses; yellow legal pads filled with lyrics-in-progress spill across the desk. A lilting, offbeat waltz—all piano, bass and drums—pours forth from the Yamaha Porta studio in front of him. As I come up behind him he grins wryly and pretends to hide the hefty, bright yellow book he’d been engrossed in. Filled with a sudden journalistic Lust for Truth, I snatch the book from his hands. Walker’s Rhyming Dictionary of the English Language. Sting cheats! “OK, OK,” he laughs boyishly. “I confess. I use a rhyming dictionary ’cause it’s a great tool.” He turns up the music and reaches for some notes. “I’m working on juxtaposing these two sets of images, one about the First World War and the other about heroin addiction in the eighties with the poppy as the unifying image. And I’m trying to make it all fit this reggae waltz.” I look skeptical. I know he’s a wiz at reconciling and blending disparate musical and lyrical ideas. But a pop song linking World War I and smack? And in waltz time? “Look, you’ve got to trust me on this. It’ll come together. Nobody uses waltz time anymore in pop music, except in a cliched, sentimental way, which is a shame. There’s real tension in the way that three pushes against the four.” I remind him that the First World War isn’t remembered as vividly in the States as in England, where almost an entire generation was lost in the trenches. “You grow up with it over here,” he responds quietly. “One of my first memories as a child was of living very close to the war memorial in my hometown. There were two statues of soldiers with their rifles turned toward the ground, and a plaque with the names of hundreds and hundreds of the local young men killed in the Great War of 1914-1918. It looked as if the whole community had been wiped out—which wasn’t far from the truth. It’s all really a function of the ignorance of the people who sent them over there. In England we have Remembrance Sunday,” he continues. “Everyone wears a poppy in his lapel on that day, which I think is a reference to the poppy fields of Flanders where a lot of those battles took place. Of course, the poppy is a symbol of death in that heroin comes from poppies and so in the third verse I link that with the ghastly industry built up around people’s addiction to heroin.”

Sting pauses, lost in thought for the moment. Suddenly he’s up out of his chair and bounding toward the kitchen. “C’mon,” he calls. “I’ll play you the rest of the demos.” Midway through the sunny kitchen we spot Sting’s 6-month-old daughter Mickey, playing on the floor. Sting hands me an acoustic guitar and suggests I play something for her. I awkwardly pick out an old folk tune. Mickey stares blankly at me and drools. “Not like that,” he grumbles, grabbing the guitar, “like this.” He knocks out a chugging Chuck Berry rhythm and stomps a steady four with his right foot. Mickey rises unsteadily to her feet and commences a wobbly but enthusiastic dance, a look of sheer delight plastered across her tiny face. “That’s my rock ’n’ roll baby,” Sting coos. He gently scoops her up and plants a tender kiss on her nose.

Sting pops a cassette into the tape player and curls up on the couch like a sleepy lion. The song is “Set Them Free.” It’s up-tempo, very catchy. Seems the most likely single. The song’s theme is intriguing and paradoxical at first glance: having to let go of people in order to connect with them in a deeper and more satisfying way. I remark that, for me, this song is the antidote to the enervating paranoia of “Every Breath You Take.”

“You’re right,” Sting agrees. “It is a paradox and a companion piece to ‘Every Breath You Take,’ which I consider to be really a quite evil song about surveillance and controlling another person. The fact that it was couched in a seductive and romantic disguise made it all the more sinister for me. Having lived through that feeling in quite a real way and seen the other side, I think the highest tribute you can pay another person is to say, ‘I don’t own you, you’re free.’ If you try to possess someone in the obvious way, you can never have them in the way that really counts. There are too many prisons in the world already; we don’t need a prison in every home.” He pauses for a few moments, then sits up as if to emphasize what comes next. “It’s not just a clever thought; it’s a genuine feeling. I’ve lost the emotion of jealousy, I really have. Some people may see that as being cold.”

“It could,” I suggest, “be just an excuse to avoid making commitments.”

Sting stretches out on the couch, staring at the ceiling. “Well, I do seem to be the type of person people like to trap.”

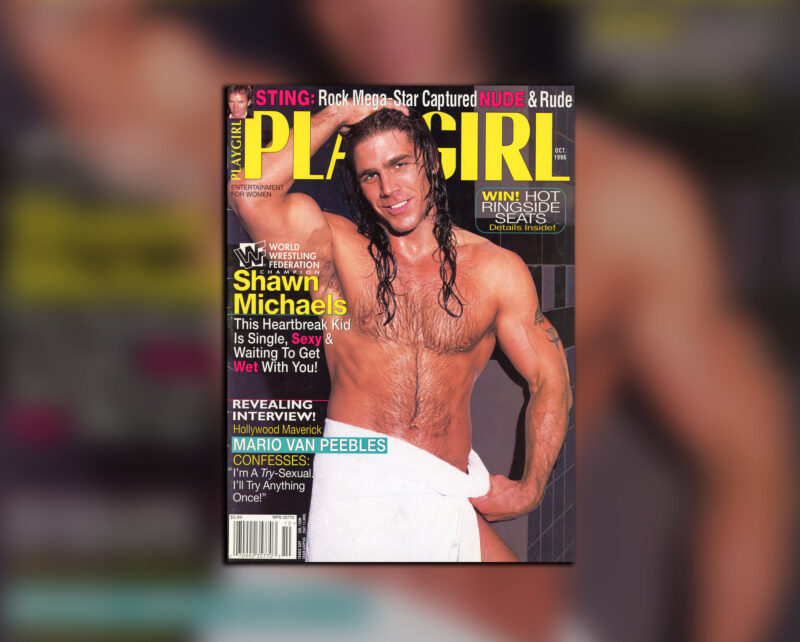

… continue reading on PLAYGIRL+