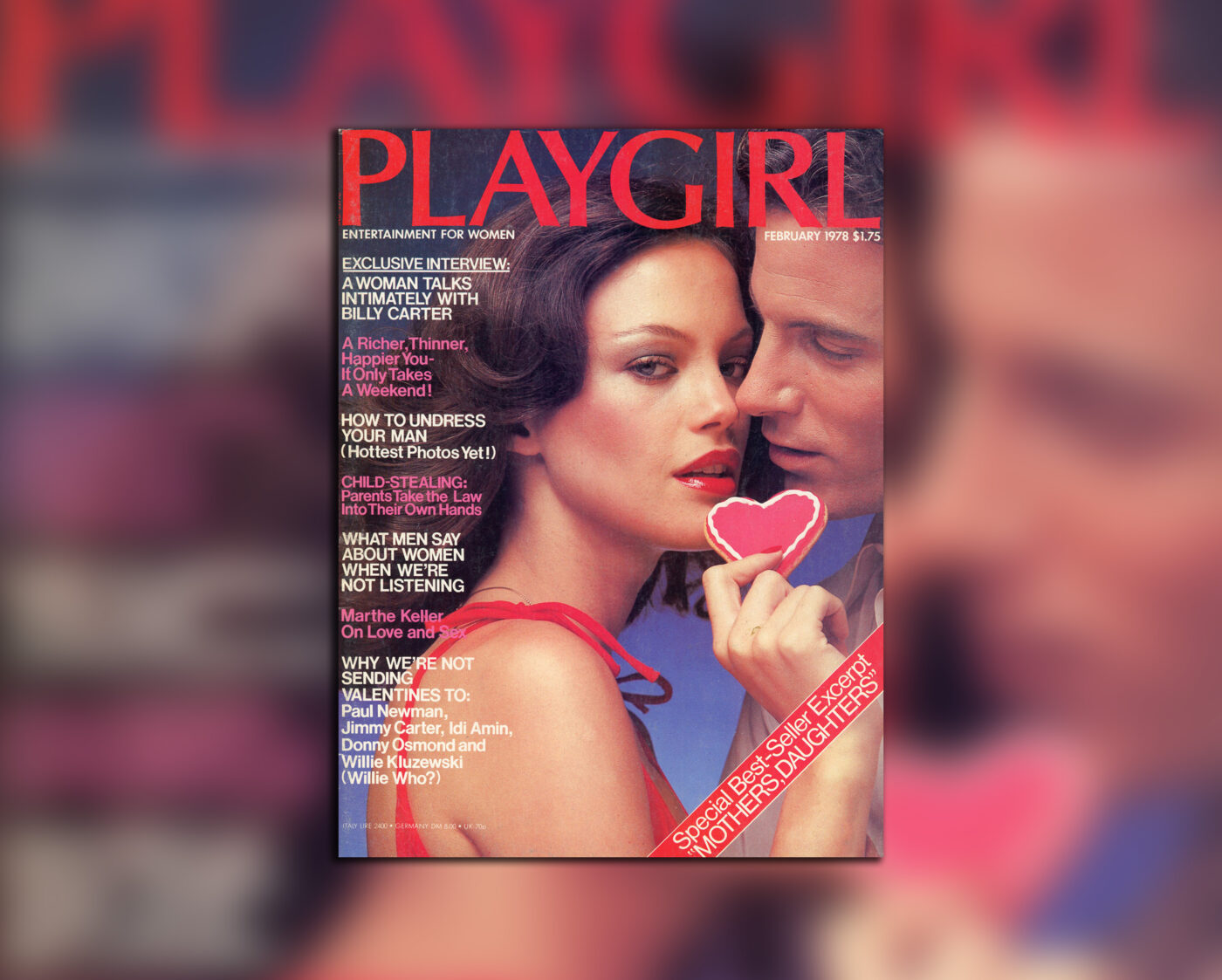

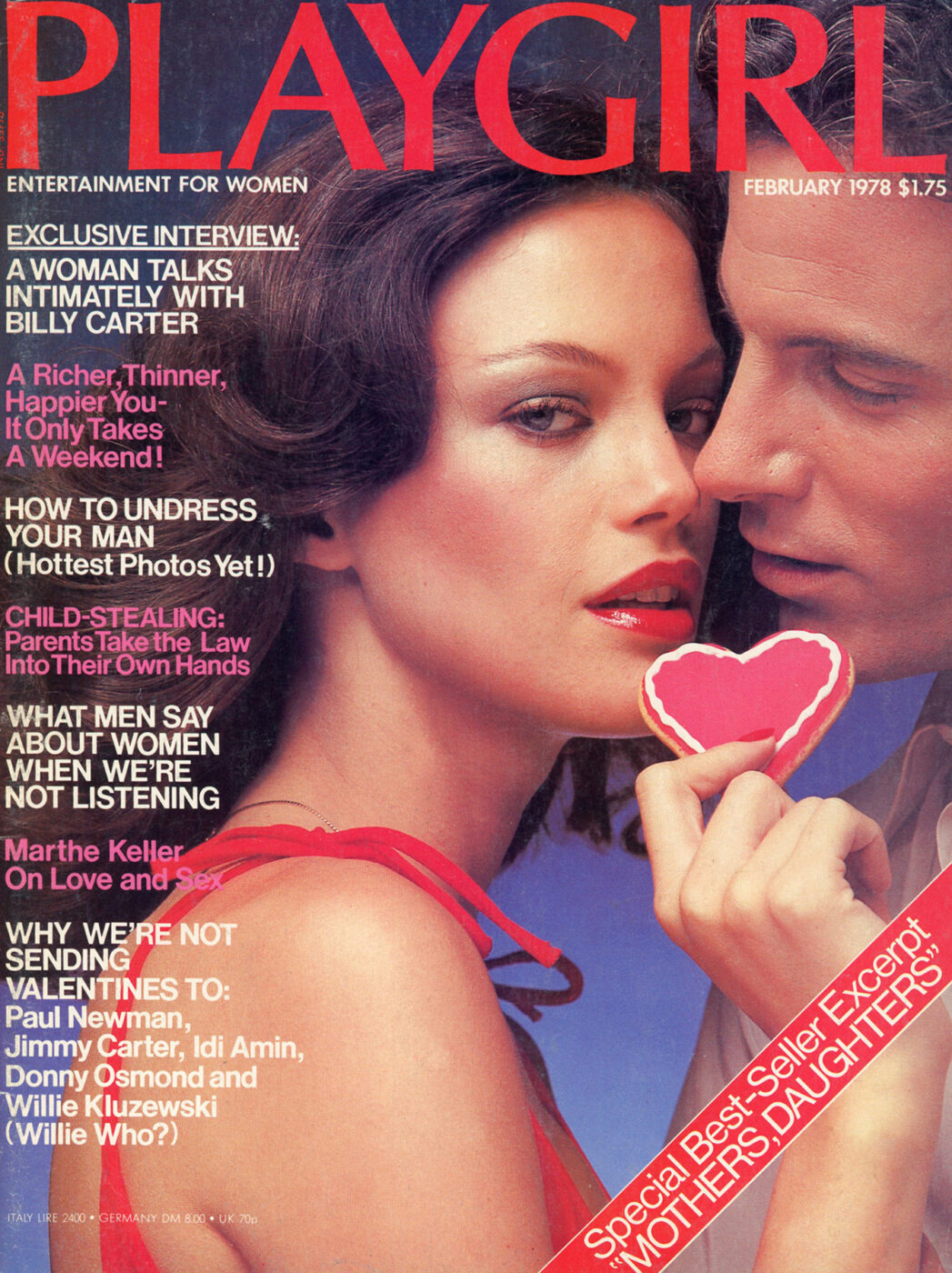

Hollywood has been consistently criticized during the last decade for not writing enough good women’s parts. Tell it to Marthe Keller. In the last two years since the stunning 31-year-old Swiss-born actress was lured from a thriving career in Europe to work in America, she has had four starring roles in four major movies, playing opposite a pantheon of male stars. Dustin Hoffman and Sir Laurence Olivier in Marathon Man; Robert Shaw and Bruce Dern in Black Sunday; Al Pacino in Bobby Deerfield; and William Holden in the not-yet-released Fedora. She has played a double agent, a Palestinian terrorist intent on blowing up the President of the United States and 80,000 others at the Super Bowl, a wealthy, beautiful European in love with a race car driver, and in Fedora both a legendary Hollywood star obsessed with growing old and her daughter.

In a short time, Keller has become the international actress of the late 70s. When she acts in French, Italian, German and American films she speaks the native language of the audiences. In Munich, Berlin and Paris she’s admired for her work on the stage. In France she’s considered a major TV star, having completed a long-running series there.

Being so international has its challenges. Director Philippe De Broca (King of Hearts, That Man from Rio) brought her to France to play opposite Yves Montand in The Devil by the Tail. It was before she spoke any French at all, but the relationship with De Broca was successful — professionally and personally. She and De Broca made two films together and he became the father of her son. Although they never married, and Keller has gone on to have long relationships with French director Claude Lelouch and Bobby Deerfield co-star Al Pacino, she regards De Broca warmly as a conscientious father and vows, “We will always be friends.”

Keller grew up on a farm near Basel in the German-speaking region of Switzerland, where her father raised horses. It was a background she credits today for giving her a sane foundation: “If I was born in New York, I’d be completely crazy, I’d be going to a shrink every day. Being Swiss, with cows and horses all around, saved me.” Tall and raw-boned, she prepared for a career as a ballet dancer until a skiing accident forced her to consider another avenue. The opportunity came when her native town gave her a fellowship to study acting in Munich at the Stanislavsky Group, where she remained for three years until joining the Schiller Theater Group in Berlin for two more years.

The astonishing versatility Keller displayed in Lelouch’s And Now My Love (she played three roles: a fresh cabaret dancer, a middle-aged survivor of a concentration camp, and a beautiful, difficult heiress) brought her to the attention of American filmgoers, and more importantly for her career, American filmmakers.

As she had in France, she began making her first American movie without being able to speak the language in which she would act. “A t first everyone worries about me,” Keller told a newspaper reporter not long afterwards, remembering the impression she made on the set of Marathon Man. “They think I am unhappy. They wonder why I speak to nobody. I speak to nobody because I cannot.”

Today she lives a remarkably mobile life befitting her international status — maintaining addresses in Switzerland, Paris and New York, and obviously making frequent stops in Los Angeles. It’s a vagabond existence that might unsettle others. But Keller revels in it. It’s in her blood, as she learned on her 20th birthday when her mother approached her, nervously, to tell her what she seemed to indicate would be a terrible secret. “She told me that my grandma was a gypsy, a real gypsy. She was so upset, I thought she would say my father was not my real father. But, you know, in Switzerland to be a gypsy is the worst thing. So sometimes I think about that. I have this kind of feeling that I never know what will happen tomorrow.”

For now, Marthe Keller can count on at least one thing. She’s the most sought after actress on two continents. British freelance journalist Roy Bennett spoke with Keller about her career, AI Pacino, her views on love and marriage—and about the fiercely independent life she’s determined to live.

Playgirl: Is it true that you could have started your movie career five years earlier, if a famous producer hadn’t made you an obscene offer in exchange for a contract?

Marthe Keller: Ya, ya. The man saw my pictures and brought me to Paris for a screen test. And . . .

What man?

He’s too famous. The man is too famous. Anyway, my pictures excited him, and he told me he’d give me a five-year contract if. . . . He said, “Would you like if I found you another woman and watched the two of you make love?” I wasn’t sure what he meant. Then he said, “Well, if you don’t like that, what about a man?” Then I burst into tears. I called him a son of a bitch in German and ran out. I was so naive that I thought, “That’s movies.” I thought movie contracts are done like that, and because I had a big hatred of that, I stayed on the stage for five years longer. But it’s not interesting to talk about because it’s so vulgar and stupid.

But it’s not naive to think that movie contracts are done that way. The casting couch is still a common piece of furniture in many Hollywood executive suites.

But I’ve always said to my friends, you can never get a part just because you’re having an affair with the producer. I mean, movies are very big business, and with all the money they spend to make a film, they better be sure that they get the best actress possible for that part—not just some girl who is sleeping around. That’s not the way to get a part.

You must have been very upset when you heard the stories about how you got your parts in Marathon Man and Black Sunday.

Oh, that was so stupid! They said I was the producer’s—Bob Evans’—girlfriend. You know, I never even went out with him—even once. They start such idiotic rumors in Hollywood. You know how I got my part in Marathon Man? I was on the stage in Europe for six years. I played more than 50 parts, did a television series and made 11 or 12 films, with Claude Lelouch, with Philippe de Broca. But it was when I was playing in Joe Egg on the stage in Paris that Dirk Bogarde and Michael York were in the audience.

How did they help you?

Well, they knew that John Schlesinger was looking for a European actress for Marathon Man and they told him about me. And then he brought me to Hollywood and I made a test with Dustin Hoffman, and that was it. But people say such ridiculous things. In Paris, in the newspapers, they said I was with Charlie Blaudorn! Once I went to dinner with John Schlesinger and what do you think the German newspapers said? That I was his mistress!

And people’s reaction to your getting the part in Bobby Deerfield?

That I got the part because I’ve been living with Al Pacino. But when the film began, I didn’t even know him! We met on the film and didn’t live together until it was finished. But how can you deal with such crazy gossip? When I hear or read things about me that are not true, I get very, very upset. I shouldn’t—perhaps one day I get used to it. Or one day I quit for that. I think I’m very honest. I have a quiet, simple life and I like the work, that’s true. But when I hear lies about me, I feel so cheap. It’s not so easy to be an actress and try to live a normal life.

Is it more or less difficult to live such a life in Hollywood, as opposed to say, Paris or Rome?

I’ve been out to Hollywood and the life mainly, for me, was no good— sometimes a nightmare. I wasn’t very popular out there. I never went to parties because you get bored to death. And they’re so self-centered. They ask me, “How are you?” and nobody waits for an answer. They don’t really give a damn how you are. And you’re always being judged. “Did you see how she looked today?” Or, “Oh God, what did you do to your hair?” How much of that can you take? Nothing but gossip. For a girl it’s even worse, because we are still objects. You read less about the man.

Your friend Al Pacino certainly doesn’t do many interviews.

For him it’s right . . . for him. I don’t know. He keeps changing. Perhaps one day he will do it again. I don’t know. He suffered also, I’m sure. But I’m not here to talk about him. But I understand more and more. I see things close, and it gets me very, very upset.

He’s an incredible performer. You must be very proud of him, as an actor and as a person.

Everything I’m proud. I’m proud to know him. He’s wonderful.

Bobby Deerfield is really his first romantic role, isn’t it?

Oh ya, the first. I think it’s very important for him and for the audience to see him in this type of part. I think he has to act less than for his other roles. Something very vulnerable comes out.

He’s playing himself more, you mean?

Right. I think it’s something that he hates probably, but it’s absolutely him.

Did he teach you anything about acting?

What I learned from Al in Bobby Deerfield was about not acting. You are always being surprised by him. He challenges you all the time. Just like in real life, you don’t know what someone will do or say. And as an actress I like these surprises. That way, what you have memorized is not always done the same way. You respond to the surprise, and so the reaction has a different color each time. That’s why I really like working with him.

What kind of a person is he off screen?

Well, some people think he is moody and very . . . you know . . . serious. But he’s not that way, really. It’s mainly the parts he plays. And, like all actors, he has different reactions to things. But I don’t like to talk too much. You know me, I’m a little bit shy. I’m happy. And it’s more than only a guy!

You’re very lucky. So many highly professional women have got an empty pillow next to them at night. They’ve got their career, but no man.

That’s true. If you are a real woman, you need somebody who is stronger than you. And if you are so strong, it’s very difficult to find somebody who is stronger. If you have somebody who is less—but nice and good— you get bored, you feel like a man, you act like a man. And you don’t want to be a man.

If you have somebody who is strong, it’s very different, because you’re fighting all the time, because—although we have faults and good qualities at the same time—a woman who has this kind of strength is very, very unfeminine sometimes. At the same time, we need to be women. I think it’s the most beautiful thing in life—I’m so happy I’m a woman.

But what you say sounds almost impossible to achieve.

It is almost impossible. No actress wants a man who is always in your shadow, who is always a little bit behind and will accept anything. I don’t want the man to accept to be dependent on me. To me he’s not a man if he accepts.

Is it a question of money?

It’s a question of authority. I want that they give us the chance to be a woman—and to be a woman means to be under and not to be the boss. To find somebody who is stronger, it is difficult, of course, if you are honest.

Have you ever tried to put a man before your career?

I tried to stop my career some time ago for somebody, and it was awful. It was awful. I reproached him, that’s all. It isn’t good.

But I like to have everything. I’m schizophrenic. If I could have two lives, I would have ten children and a country house and flowers on the table every day and animals—and only think about what could I cook tonight for my children and for him, to make everybody happy. And sometimes I want to be a movie star. I want people to accept me the way I am. I want everything in life. It’s impossible, but you try. You try everything in life. I never regret what I did—I only regret what I didn’t do. So, I did everything. I am completely calm. I am satisfied.

But are you prepared for a succession of lovers in your life—the sacrifice you might have to make if those two schizophrenic lives you just mentioned don’t harmonize.

I’m prepared for nothing. I don’t want to prepare for a man. If it happens it’s an accident, a beautiful thing, but I’m not prepared. I don’t think about that; I don’t think about men.

And the word “lover” makes me frightened. I hate that. A lover means for me—and perhaps it’s an English misunderstanding—something very dirty. I prefer the word “friend.” An actress who has a lover is—ech! I prefer to have something completely crazy and platonic than to have a nice weekend with an actor. That’s shit. I don’t need that. I had everything, I know it. It’s all the same. After you know, how can you get out of that? And you pay such a price!

I believe that a director and the secretary go away for a weekend because they need some craziness, they need some going away. But we go away every second when we’re in front of the camera in a way. That’s why I hate to make love scenes, because they don’t really take you away like ordinary scenes. But you have a kind of satisfaction being an actress, because it’s crazy, completely crazy.

What about nude scenes?

Oh, I hate nude scenes! I’m drunk three days before and three days after. But really, the only time I made a nude scene was in Marathon Man. Only a few seconds. And it really belonged in the story. You had to see these people together. And, of course, John Schlesinger did it in perfect taste. There was nothing cheap about it, and that’s the main thing—you have to trust your director, and he has to have class. But I really dislike very much doing it, and I wouldn’t do it again…

…Keep reading on PLAYGIRL+