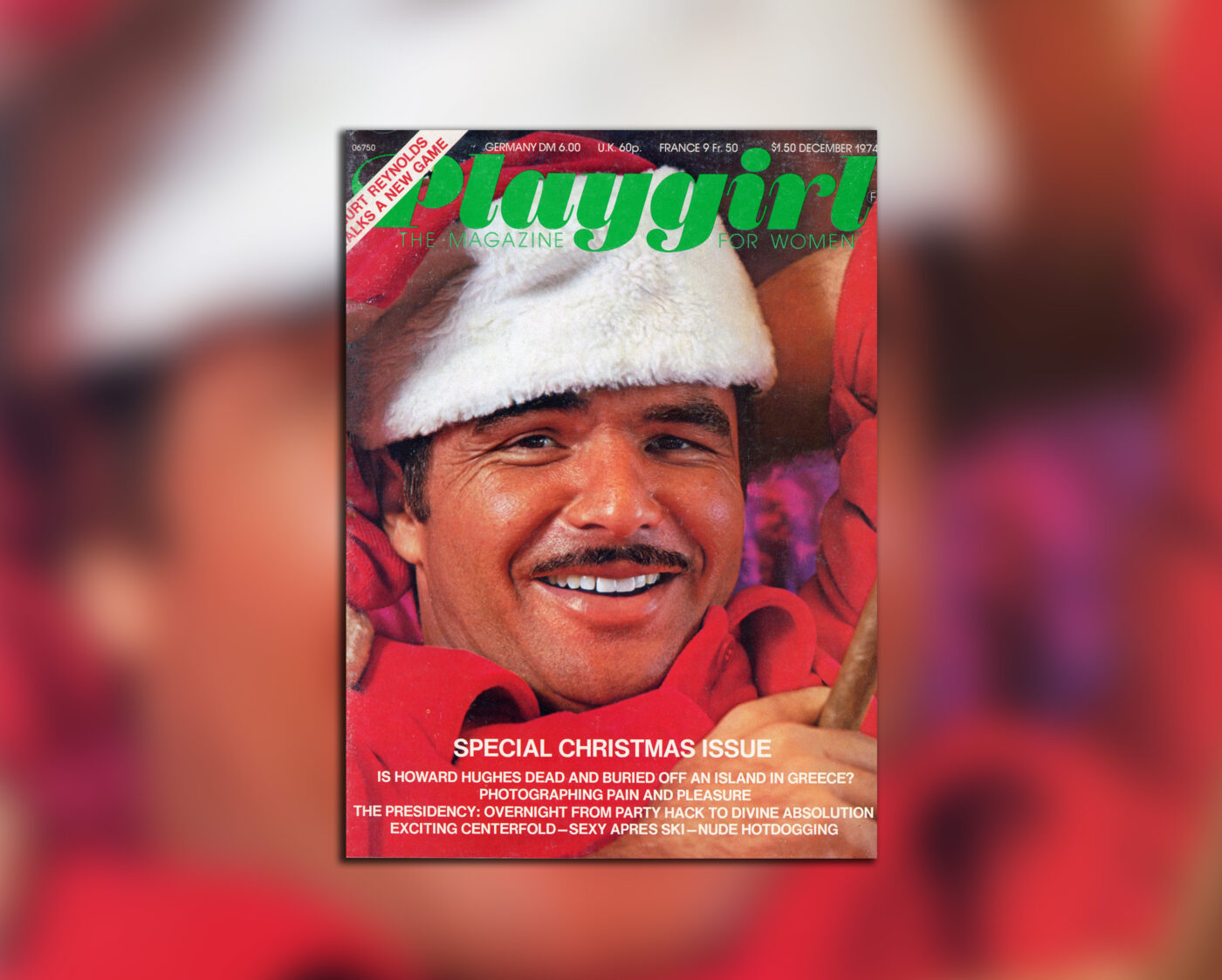

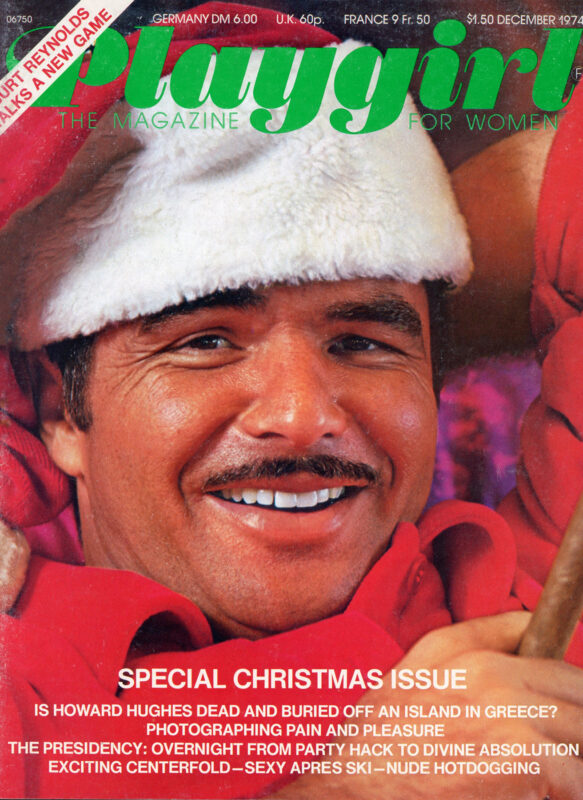

Only haltingly and after a long, loose lunch in which we trade lies and a lot of mutual like, does Burt Reynolds confide where he is, where he really is at this point in his life. “I am on the verge of making my big move now,” he says after a long, wary pause. He knows that these words, shaped by an unfriendly hand, could make him sound like a bragging egotist — which he is not. Reynolds knows and everyone who knows him knows that he doesn’t make a habit of babbling on about his greatness. When he does talk about himself, his words are usually self-mocking. But here in this interview situation and under casual prodding he admits he’s elated at this period in his life on several counts.

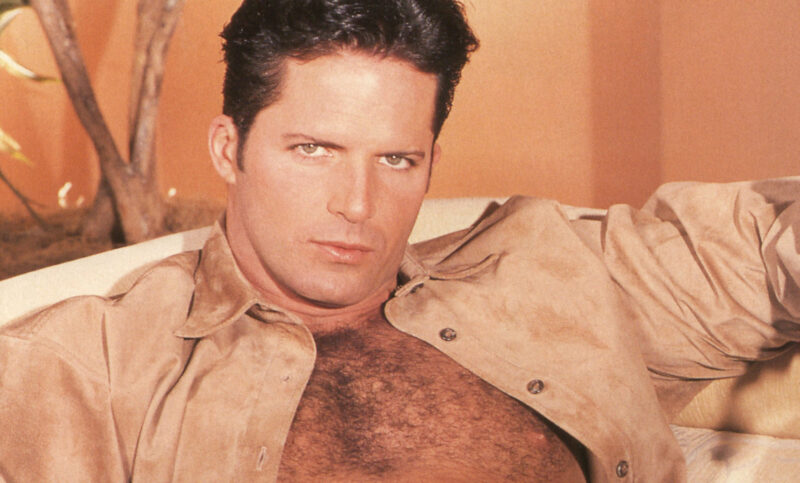

One, he’s just finished a first-ever for himself, singing and dancing the lead with Cybill Shepherd in Peter Bogdanovich’s tribute to Ernst Lubitsch and Cole Porter, At Long Last Love. Burt got good personal notices for his last film, The Longest Yard. Daily Variety hailed his “genuine star power” and Newsweek his “engaging athletic grace and easy openness.” But in it, Burt played another one of those silly macho parts, which did nothing to shake his image as “the male Raquel Welch.” Now, in this Bogdanovich film, Burt says, “All of a sudden I’m Cary Grant, my lifelong hero, standing in a room with a cocktail glass. Now let’s face it, there are a lot of guys in this town who look a helluva lot better with their shirts off than I do and play those kinds of parts better than me, but I don’t think there’s anyone in this town my age who plays light comedy better than I do.”

“Cary Grant is the best at comedy, but Cary works for Faberge [translation: he isn’t making many, or any, movies any more]. Marlon Brando admits he doesn’t do comedy well. And the kind of comedy I’m talking about isn’t two or three funny lines in a picture: I’m talking about that kind of sophisticated comedy that Grant does so well which I’m doing in this film. That could change things around for me drastically. I’ve waited a long, long time to do the kind of story I’m doing with Bogdanovich.”

There’s another breakthrough. When he finishes At Long Last Love, Burt Reynolds goes into another feature, this one a love story with Catherine Deneuve which he’s co-producing with Robert Aldrich called City of Angels. “I’ve waited an awful long time to do a love story, and this is one that I will have a hand in casting and cutting and selling besides, and I’ll be able to direct my own pictures.”

And, as if that weren’t enough, Reynolds adds the final zinger, this time about his own love life: “I’m on the verge of breaking out. I feel that something’s going to happen. I don’t know what it is. I don’t want to lose my best friend (Dinah Shore). But I feel terribly vulnerable right now — like I may look up at any moment and see that girl running across the field.”

“That girl” is the girl of his dreams, not Dinah, probably not even an actress, someone who on the outside is so terribly ladylike he could just imagine her playing Julie Andrews’s part in The Sound of Music, a woman who would be fresh-faced and freckled and look like an ex-nun in a field of wildflowers singing Rodgers and Hammerstein tunes in a clear, virginal voice — and who, in the privacy of their marriage bed, would come on like a jungle tigress and shock him with fire and lightning.

Even for a superstud superstar, there is a time, apparently, to tear and a time to sew, and Burt has come to one of those creative plateaus that come to many men at one time or another in their lives when they are happy enough with themselves and with what they are doing so that they need and want to share the happiness at the deepest human level: in love and marriage. Burt doesn’t articulate this thought in terms that are either very poetic or even analytic. He covers up his own feelings by making a statement about someone else (although he is clearly thinking about himself): “Marriage is gonna be ‘in’ again. Brenda Vaccaro and Michael Douglas have been living together for about four years, and now I hear they’re thinking about getting married.” But it is clear, most especially because he is so unglib about it, that despite the fact that he hasn’t even met his dream girl yet, Burt Reynolds, superstud, is ready, willing and able to be tamed.

Burt had a three-year marriage (to British comedienne Judy Carne), he’s seen a universe of women before and since that marriage, and he thinks he knows what he wants. And he’s enough of a romantic to believe that what Buddy wants Buddy gets.

He learned that early in life. As Buddy Reynolds (his dad was Burt, a low income and therefore honest cop in West Palm Beach, Florida), he found that his own drive and desire could get him into the mansions across Lake Worth where concupiscent little rich girls would welcome even a poor cop’s kid to their pink and white boudoirs if the poor cop’s kid also happened to be an All-State fullback with scholarship offers from twenty-six colleges.

Buddy Reynolds was lean. But he was fast, and he had the ambition that comes from living on the wrong side of the lake and a sense of humor and a roguish grin on his face and an ability to put people on.

“They flew me all over the country to look at campuses, and I finally decided on Miami. I signed a letter of intent at the University of Miami where they offered me lots of nice things,” recalls Burt, “and then I went up to Florida State to talk to Coach Tom Nugent. He should have been in show business. He said, ‘I know what Miami must have offered. But I’m offering this.’ He pointed to a picture of the Florida State campus. ‘What?’ I said. What are you offering?’ ‘The whole school, boy, the whole school.’ I wondered what he meant, and he could see I was wondering so he spelt it out. ‘You’re goin’ to be starting against Alabama and Mississippi next fall, and you know how many girls go to this school, boy?’ I shook my head. ‘Two to one, son; two to one.’ I said, ‘Where do I sign?’”

Buddy didn’t know it at the time, but Tom Nugent had made the same speech to one hundred sixty-seven other potential stars who also signed at State and he had to fight for a spot on the team. But he had the moxie to make the team and in two years he scored — on and off the field. That same moxie led him into acting. “There’s something in a good football player,” he says, “that makes a good actor. In football, if you have a modicum of natural ability and a great deal of desire you can sometimes become a star. In acting, you get the same kind of chance. I know seven or eight football players who’d be wonderful actors. Don Meredith, for instance. He used to come into a room and do a little number: ‘Ah’m Leroy Jordan and ah just like to hit people and knock ’em down and jump up and down on ’em and ah’m a great lay.’ People used to say, ‘Ain’t he cute?’ But in five minutes he’d have the whole room absolutely psyched. I think he even got laid —once or twice.”

By now, everyone knows the details of Buddy Reynolds’s rise to stardom, how he lost his spleen in an auto accident, quit football and got an acting scholarship in New York, won a part in a stage version of Mister Roberts with Charlton Heston and Orson Bean (and became Burt at last), started playing cops and Indians (he is one-quarter Cherokee) on TV, fought casting directors who thought he looked too much like Marlon Brando, starred in two big series, Hawk and Dan August, charmed late-night viewers of the Johnny Carson show with his impish wit and ready quips and won the role of the macho bowman, Lewis, in John Boorman’s Deliverance. There was talk of a nomination for the Academy Award. And how a magazine editor met Burt on one of those Carson shows and decided that he was the perfect male sex symbol to pose in the buff in a centerfold send-up of Playboy. He did pose, gratis, “for the fun of it.”

Funny thing happened, however. The picture didn’t turn out to be such a sendup after all. Burt says, “Masters and Johnson and a lot of other experts said that women weren’t turned on looking at pictures of males. I think they loved the humor of the picture, and some were even turned on.”

Were they! The magazine editor looked at the sales figures of that issue and asked Burt if they could market the picture as a poster and split the profits…

… Keep reading on PLAYGIRL+