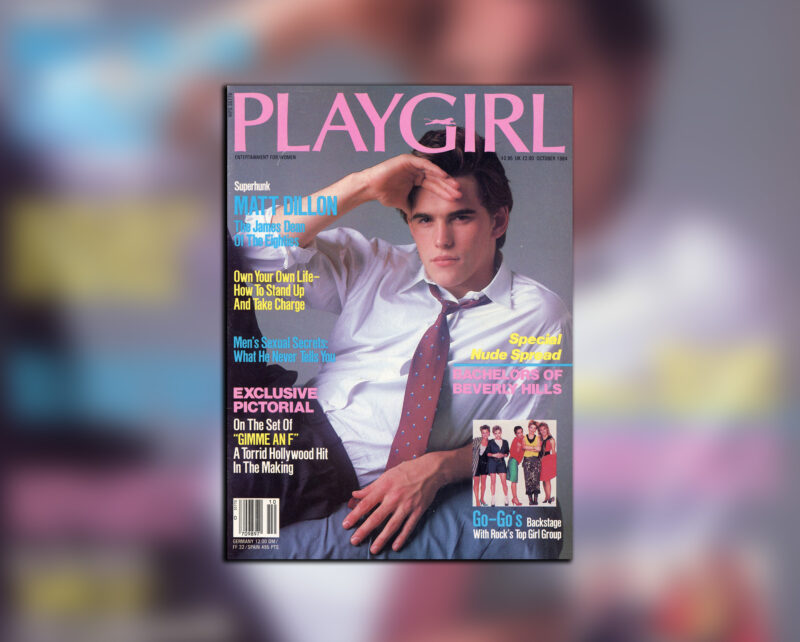

Despite the immensity of the American disaster of the 1980s, and even amid the grisly coincidence in California of holocaust and geological upheaval, tiny parts of the existing culture were left for the eyes of history. To the north of Los Angeles, where the land was so fiercely squeezed together, one house was preserved between sheer walls of rock. The human figure found in this best-known excavation—the one archeologists have called Mulholland Man—has lately been identified as an actor named Jack Nicholson.

The more we learn about him, the more clearly he is revealed as not just a surviving specimen, but a very representative figure. The city to the south of the site must have known millions like him. The fossil of Nicholson, its outline nearly luminous with a mixture of cocaine and volcanic dust, was found spread-eagled in what may have been a pleasuring room. Several unidentified female fossils were discovered in the same area in postures of abandon. Burned in the wall above the figure was a text, either of an interview he must once have given or of a dialogue with himself.

It has all the formalized but sentimental self-analysis of America before the Disaster. Nicholson is asked, “Can you characterize Jack Nicholson in one sentence?” (The single sentence was such a fetish then.) He replies, “He just wanted to make it nice.”

Jack Nicholson: born April 22, 1937, Neptune, New Jersey, the only son of John Nicholson, a sign painter, and Ethel May Nicholson. Jack was not yet born when his father left home, and his mother set up a beauty-parlor business to survive. Whenever Jack saw his father as he was growing up, it was in bars. “He was an incredible drinker. I used to go to bars with him as a child, and I would drink eighteen sarsaparillas while he’d have thirty-five shots of three-star Hennessy. But I never heard him raise his voice: I never saw anybody be angry with him, not even my mother. He was just a quiet, melancholy, tragic figure—a very soft man. He died the year after I came to California.”

That was 1958 and Nicholson was playing the horses and trying to act. He did not go back East for the funeral.

His friend, Bruce Dern, once said: “The best thing that ever happened to him is, he has probably come further from what he was raised in than any of these other guys that have made it… He lived on the bad side of the tracks until he was about thirteen, and then somehow shook it out, and he’s always tried to impress people with how sharp he is, how intelligent he is, how quick he is.”

His is a level, straight-on face, ready to take the least slant or decoration. Perhaps it’s because the face can be so restful that he can look so young still. When he chooses, he can make the face seem as bare and balanced as a ball. It’s only then that the range of warning grin, depressed reverie, and heartwarming smile can operate. And it’s only above the regularity of the ball that he can do so much with a head of hair that seemed straggling and receding as long ago as Easy Rider (1969). The face was greedy and the hair floppy in Carnal Knowledge (1971). In The King of Marvin Gardens (1972) the hair was cut short, tidy, and anonymous, and the character wore spectacles. There was a warm, flowing mustache for the lover in A Safe Place (1971); a clipped, military one, along with a crew cut, in The Last Detail (1973). Then came slicked hair, a central parting like a scar, and a woefully wounded nose in Chinatown (1974). In One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) he had an unkempt widow’s peak, and in The Shining (1980), he could have been the image of his bearded director, Stanley Kubrick.

It is as if the face has altered during the period in which and process by which the actor has worked himself into the role. No change is dramatic, but as the face shifts and slides, you wonder what Nicholson really looks like. An actor’s face is always waiting for the game of a part. Alone, he might be sunken and blank.

Robert Eroica Dupea in Five Easy Pieces (1970) is a man in hiding. He lives with a waitress, Rayette, works in an oil field as a hard-hat rigger, and calls himself “Bobby.” We learn how great an act of self-denial this is when he travels north to the family home in Washington State to see his sick father. It is a musical household on a sheltered, offshore island. Bobby was once an accomplished pianist, and he plays again in an attempt to woo Catherine, the fiancee of his brother. But Rayette has come north too, and her appearance destroys any hope of a new, more understanding love. Bobby tries to talk to his stricken father, but the older man is paralyzed and apparently without sense. Bobby and Rayette prepare to drive “home,” but when they stop at a filling station he leaves her and hitches a ride on towards Alaska, escape, and more secure hiding.

I’m not terribly thirsty for the limelight, but obviously you don’t get into the movie business if you want to be a recluse – Jack Nicholson

His education never went beyond high school, but he traveled to California in his late teens out of the all-American urge to see movie stars. His was probably the last generation when anyone felt that way: James Dean had been killed only three years before. Nicholson found work in the cartoon department at MGM, and producer Joe Pasternak told him to try acting. So he went to the Player’s Ring Theatre and studied under Jeff Corey, a teacher whose approach was based on improvisation.

He spent ten years waiting for his break, taking whatever jobs came along, forming his friendship with Monte Hellman, and generally serving in the strange band of talents that producer Roger Corman hired for next to nothing.

Before Easy Rider, he was in twenty pictures. He had bits in prestige jobs like Studs Lonigan (1960) and The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre (1967), and leads in exploitation movies shot in a week—The Cry Baby Killer (1957) and The Wild Ride (1960). He worked for Corman himself—as a very funny victim in a dentist’s office in The Little Shop of Horrors (1960), in The Terror (1963), and The Raven (1963), and then scripting The Trip (1967), a lurid realization of LSD hallucinations, something Nicholson had first tried as a volunteer in laboratory experiments.

But in 1968, with a new friend, Bob Rafelson, he helped write and produce Head (1968), a startling satire on the media and the Monkees. Next year, it was the insistence of Rafelson that got Nicholson the role of the disenchanted Southern lawyer in Easy Rider when Rip Torn walked out on the project. Nicholson has never looked back. His few scenes in that huge success were a focus of humanity and humor, and for the first time a middle-class audience could enjoy a movie in which an actor was plainly stoned. Not the least part of Nicholson’s genius is in being capable of communicating while he is high.

“They don’t have no wars, they got no monetary system, they don’t have any leaders, because, I mean, each man is a leader. I mean, each man: Because of their technology, they are able to feed, clothe, house, and transport themselves equally—and with no effort.” –Jack Nicholson as George Hanson in Easy Rider.

“Jack is a little boy trapped in a man’s body.” – Sally Struthers

Sally Struthers was a small-part actress who had a four-day part in Five Easy Pieces. She was one of two women in the movie that Nicholson and a friend pick up at a bowling alley. After the four days, some time passed, and then Struthers got a call from the production unit to come back for the love scene with Jack. She said it was the other woman’s scene in the script, but they told her not to worry. The two were called Betty and Twinky, and no one ever knew which was which.

Struthers was very nervous and shy, but the wardrobe and makeup people got her down to her underpants. She felt worse still, and angry, when she saw that Nicholson was going to play the scene in boots jeans, and a Triumph T-shirt.

She was allowed to put on jeans when, on one take, her leg was cut on some Venetian blinds. But Triumph remained as he carried her round the room, her legs wrapped round his waist. It is one of the best fucking scenes in the movies.

WOMEN IN AND AROUND NICHOLSON’S LIFE:

■ His mother.

■ Two sisters.

■ Sandra Knight, his ex-wife. They were married from 1961 to 1966. She was an actress, and appeared with him in The Terror, playing a ghost he falls in love with. The divorce was, in his words, “a clear, nonviolent, non-tumultuous decision.” She was getting into mysticism, and he wanted a career so badly that he was acting by day and writing a screenplay at night. “We just grew apart. We were so obviously going in different directions that we were becoming a burden not only to each other, but to our child.”

■ Jennifer, his daughter by that marriage.

■ Karen Black, who acted in Drive, He Said (1972) under his direction, and who played Rayette in Five Easy Pieces.

■ Susan Anspach, pre-Raphaelite, musical and sensitive as his northwestern affair in Five Easy Pieces. According to published accounts, Anspach has had a child by Nicholson.

■ Helena Kallianiotes, who played a mad, aggressively talkative hitchhiker picked up in Five Easy Pieces.

■ Tuesday Weld, the girl searching for a reconciliation of past and present in A Safe Place (1971).

■ Susan (Candice Bergen), Bobbie (Ann-Margret), Cindy (Cynthia O’Neal), and Louise (Rita Moreno), the women with whom Jonathan (Jack Nicholson) shares Carnal Knowledge.

■ Michelle Phillips, onetime singer with the Mamas and Papas who wanted a movie career. She lived with Nicholson, both in the same house and in adjoining houses; they sometimes talked of marriage. Nicholson had started dating her after her eight-day marriage with Dennis Hopper came apart, but only after clearing the arrangement with Hopper, a co-star in Easy Rider.

■ Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher), the tranquil tyrant who inspires the noble hatred of Randle P. McMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

■ Anjelica Huston, daughter of the director John Huston (nemesis of Jake Gittes in Chinatown), and occasional actress. The two have been together now for several years, and it was Anjelica who gave evidence when Roman Polanski’s trouble with the law occurred in Jack’s house.

■ The Nordic blonde in The Shining who waits alluringly in the bath for Jack Torrance, steps out naked to meet him, but turns into an ulcerous, screeching hag when he kisses her.

■ Cora (Jessica Lange) in The Postman Always Rings Twice (1981)…

…Continue reading on PLAYGIRL+