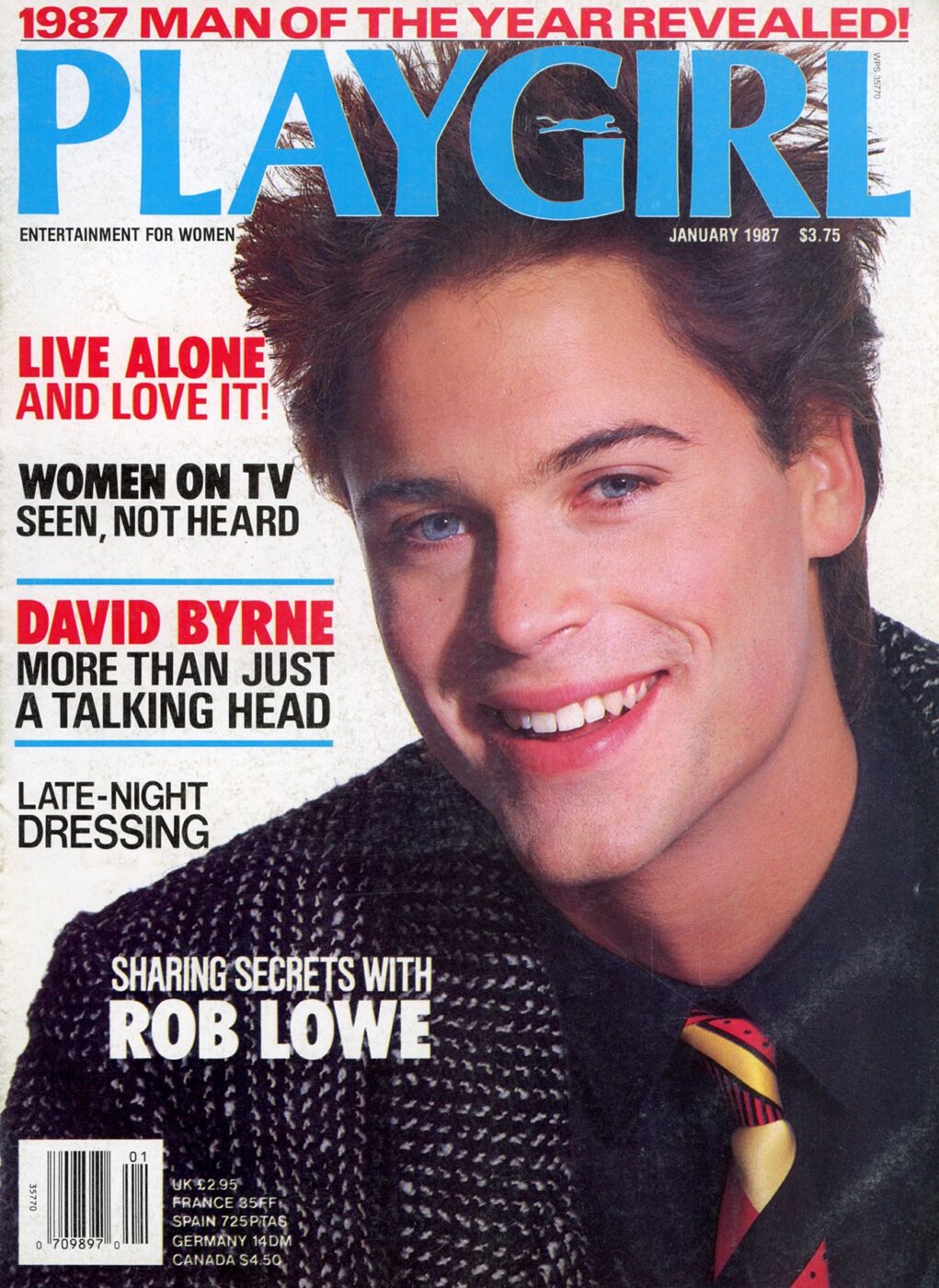

Excerpt from Playgirl, January 1987

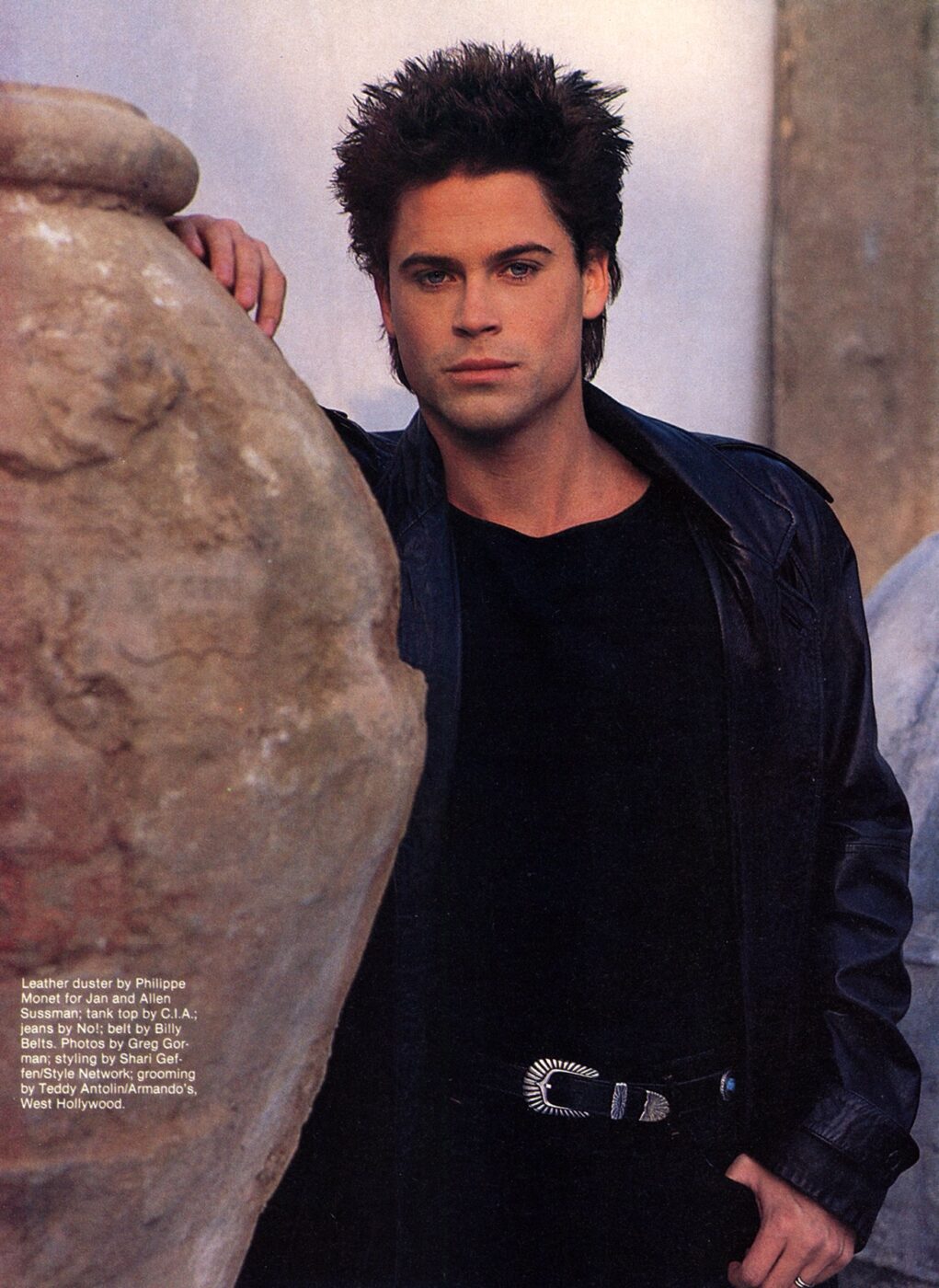

Rob Lowe picks up the white electric guitar and postures with it, looking like a real musician, his instrument cocked and ready to play. His face mimes a musician’s rapt intensity. Then he relaxes into a regular, blazing Rob Lowe smile. You have to admit to yourself that he looks a little silly—the snazzy guitar, coupled with the gray gym shorts, white T-shirt with a child’s primitive drawing and lettering on it, gym socks and shoes, single stud earring in his right ear, Clark Kent glasses, hair standing straight up. The room is decorated with a couple of movie posters, another electric guitar, a speaker and a view of the Columbia Pictures studio lot, other office buildings across the way.

“Do you play?” you ask.

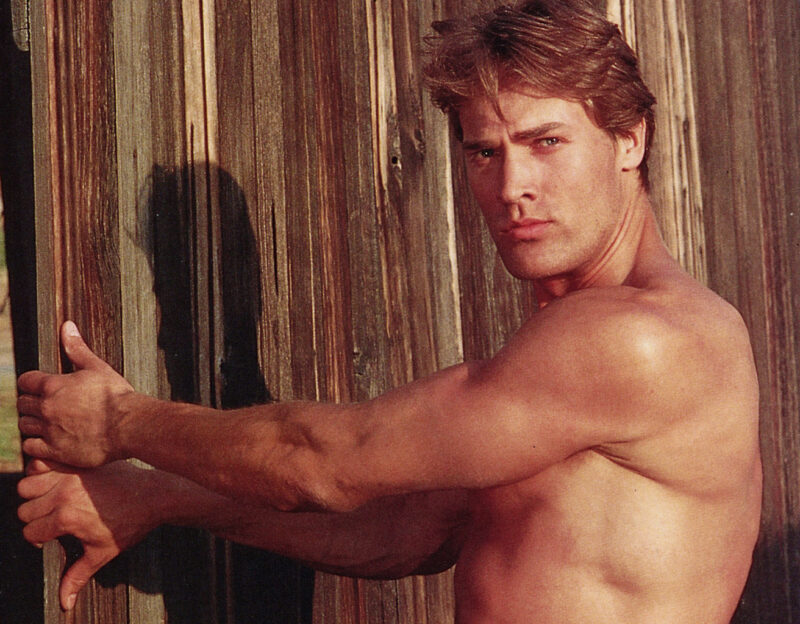

“No,” Lowe says, sheepishly. Then “A little, actually.” He wants to produce a movie about singer Eddie Cochran and has written and turned in the screenplay just today to the studio brass. Maybe he’s nervous. Every so often, when he speaks, he stammers slightly, repeating three or four times, softly, the first syllable of a word. But it is charming. Rob Lowe is beautiful and charming. You might even have to admit that he’s smart. Taken in parts, all of Rob Lowe is pretty stunning. The problem, you think, is when you add all the parts together. He looks so very young and handsome, as long as he is quiet. Then he speaks, and he sounds like a Hollywood veteran of 20 years. The shrewdness under the perfect surface is disconcerting. You wonder how long he has been 22 going on 50. You wonder if he has ever been in psychotherapy.

“I’m full of angst,” he says, about waiting for the studio to pass judgement on his Cochran project. “But my guitar is getting better. I’ve had a coach come in.”

Lowe has had a peculiar career, based until very recently on little more than his outrageous handsomeness. A couple of after-school television specials, a short-lived TV series, a small role (supposedly massacred on the cutting room floor) in director Francis Ford Coppola’s The Outsiders and a co-starring role in Class. Then the teenaged girls noticed him and the film critics took umbrage to this notice. In The Hotel New Hampshire, Oxford Blues, St. Elmo’s Fire and Youngblood, little girls screamed at the sight of him. The critics, for the most part, screamed, too—that he had little or no talent other than what was superficially visible. That changed last summer when About Last Night, with Demi Moore, got terrific reviews, and Lowe got taken seriously. And Lowe got hot, trying to produce his own starring vehicles, sitting in his office at Columbia as the phones ring off the hook. You think that his affiliation with that group of scowling young method actors, the Brat Pack, certainly hasn’t hurt him. And, to his credit, he doesn’t scowl. Polite, you think. Articulate. Slick? His rumored success with women hasn’t hurt either.

He’s about to be seen in a new film, Squaredance, in a surprising, small role opposite Jane Alexander and Jason Robards as, in his words, “a mentally retarded Texan.” He dyed his hair red to play this character, and braved a summer in Texas—“Guerrilla moviemaking,” he calls the experience. This sounds so offbase for this young, romantic leading man that you wonder if he is being completely on the level.

“It’s a Rob Lowe movie,” he says. “There’s gotta be a scene where he kisses the lead actress.” He laughs. “The movie is about a 13-year-old girl coming to grips with her family, her past and who she is. My character falls in love with her and, mentally, we’re the same age. But she’s growing up, and I’m not growing up. It’s a very dear story. Anyway, she’s my love interest. There is a sweet scene where I kiss her.”

So, you ask about his obvious integrity in choosing roles, and he segues into what a crapshoot working in Hollywood can be. He’s pleased with the success of About Last Night: “It’s not an event picture, it’s not a sequel. It’s a good, quiet picture,” he says, and then muses about his friend Tom Cruises’s enormous summertime hit, Top Gun. He says, “All it would have taken is one stray missile blowing up some kids in Libya, and Top Gun would have been in the toilet. I said, ‘Tom, you better hope our military never fucks up before your movie opens, or you’re in bad shape.’”

Then you mention his steamy love scenes in About Last Night with actress Demi Moore, who happens to be his friend Emilo Estevez’s girlfriend. “I talked to Emilio,” he says, “and he was kind of uptight about it. I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me, champ.’ He said, ‘Well, what if it was me and your girlfriend?’ I said, ‘Well, I guess I’d rather it would be you than someone I didn’t know.’ He said, ‘Yeah, yeah, that’s true. I hadn’t thought of that.’ It’s very difficult going out with anybody in this business, and this kind of thing is the first step to paying the price. It hasn’t affected any of our relationships. It’s great, because now Demi and I have a common ground, as well as Emilio and I. It’s a source of a lot of good jokes, actually.”

You watch Rob Lowe’s eyes drift toward the outer office as the phone rings. You know he’s itching to answer it, yet holding himself back. He explains that his assistant is on vacation in London. You ask him if he considers himself driven, obsessive, or merely wildly ambitious.

“Not obsessive,” he says, listening to the phone ring. Finally it stops. “Driven wouldn’t be bad. Obsessive is a little strong for my taste. An obsessive person would have run out and answered that phone. I just let it ring. It can only be the studio calling to say that they hate the first 10 pages. Let it ring.” He laughs. But you’ve struck some sort of nerve—he worries this line of thought like a dog with a chew bone. “Obsessive implies that something is lacking, it isn’t quite right. I wouldn’t want to be obsessive about anything—your focus is too narrow, you’re not seeing the whole picture. You have to have a sense of humor about yourself. I sometimes feel that the Reality Police are going to bust into the office and say, ‘OK, Mr. Lowe, where are your credentials?’ I’m just a kid from Ohio.” The phone rings again; his face looks pained. “Now,” he says, “a driven person can answer the phone when it rings a second time.” He answers the phone.

You witness a real display of acting. Lowe pretends to be his own assistant, stating that “Mr. Lowe isn’t here,” and politely answering questions monosyllabically for 10 seconds. Then he hangs up. He tells you that it was two girls on the phone, one pretending to be the operator placing a collect call, the other playing the caller. He says there was a lot of giggling. He claims this happens all the time. The phone interrupts twice more, and each time Lowe pretends to be his assistant. One of the times it is a radio station calling for an interview. Lowe rolls his eyes as he tells the radio station to call his publicist. He can’t remember the publicist’s phone number, nor can you. He fakes it, skewing a couple of digits.

You comment on how successful Lowe has been, a kid from Dayton, Ohio, with no Hollywood connections turned into a real star. You’re surprised to find out that he’s the type who always thinks he’s got miles to go before he sleeps—hard on himself. “I haven’t had a $100 million film,” he says, as though checking off items on a list in his head. “I haven’t won any Oscars”—you note the plural. “My producing credit isn’t on the screen yet. There’s all kinds of stuff. I feel like I’m just starting. People say, ‘Isn’t it great the way things are going for you. Smell the roses,’ and I do. I do. But not a lot. I hate that kind of ambition; it’s just nauseating. I’m not like that. There was a time when my work really took up my whole life, and it doesn’t anymore. I’m concentrating on other things, too, like relationships. Or this antitoxics initiative I’m working on, or voter registration. I’m 22 years old and I’ve never voted. I want to do some public service announcements on that. You have to find other things to balance out your work.”

So, you ask Rob Low about his politics, expecting lip service rather than passion. But he gets worked up. The suggestion that actors ought to keep their politics to themselves irks him. “It’s everybody’s right to be political,” he says. “Maybe I’m being irresponsible, but I feel that I’m a citizen of this country and a person first, an actor second.” He talks about his work on the antitoxics initiative on the California ballot in November, then says, “but I have yet to take a public stance on any real political issue. I have feelings on issues, but I haven’t taken any abortion stance, for example.” You know where you’re heading. First, you ask him about his feelings on the Reagan administration, and he makes pithy comments on defense paranoia, communism paranoia and a general inability to admit to being wrong. “I’m not a rabble-rouser,” he finishes, looking a little paranoid. “Reagan has done certain things that I like, and certain things that I don’t like…”

… continue reading on PLAYGIRL+