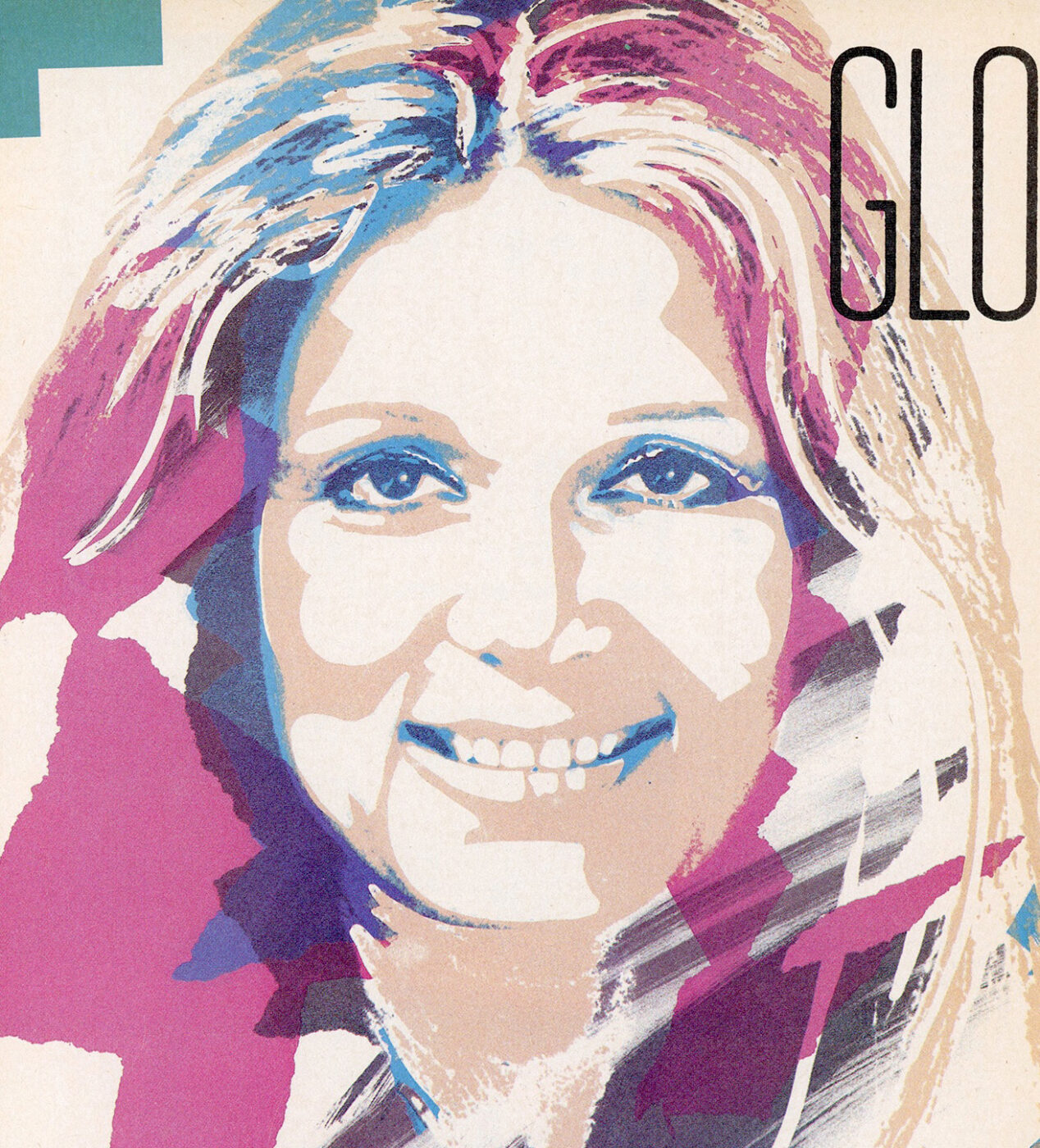

Excerpt from Playgirl, May 1985. IN THE LATE 1960s, GLORIA STEINEM LEAPED TO national prominence as leader of the then-nascent women’s liberation movement. A Smith graduate and New York magazine writer who had once worked as a Playboy bunny for a story, Steinem was the prettiest of the “bra burners,” as hecklers quickly labeled these upstart females. She marched, spoke, wrote and even started a magazine, Ms., to promote the cause of women’s equality. Through her words and the example of her own life, she forcefully made the point that women’s experiences are valuable—just as valuable as men’s. It’s an idea we may take for granted today, but remember—as Steinem notes in her book Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1983)—less than 30 years ago the prototypical college alumnae note read: “Sophia Smith Jones, ’56, has completed her Ph D., done volunteer work, and has begun several teaching jobs while having four children and following her husband, John, in his corporate career.”

As a result of all her activity, Steinem’s face became a fixture in the American consciousness: the long, straight hair parted down the middle, the cheerful features, the trademark aviator glasses. She neatly contradicted the extremist factions that claimed feminists were scowling man-haters clad in army fatigues and combat boots, and defined a new, attractive role model for the independent woman.

Steinem’s success, however, has not been without controversy. Screw magazine once ran a nude caricature of her and invited fans to “pin a cock on the feminist.” Another time, Steinem tuned into a TV commercial for an exploitation novel that showed a scantily clad woman, with longish hair parted down the middle and wearing aviator glasses, slinking over to a coffee table where she grasped a large feminist medallion.

A voice announced: “She used men—but she preferred women.” And over the years, those with little understanding of feminism have tried to blame Steinem for almost all the ills in woman-man relations in America.

Today, at 51, Steinem has lost none of her aura. Her face still looks remarkably fresh and unlined, and her figure remains slim (although she has admitted, “There are only a few minutes each day when I’m not thinking about food”). From time to time during the interview she chuckles easily, softly. There are some moments of hesitancy that hint at shyness. Indeed, Steinem has noted that despite her constant appearances on TV and at college campuses, rallies and women’s conferences, she has had to overcome a tremendous fear of public speaking.

The furnishings of her office at Ms. display the different sides of her personality. One wall shows a playful photograph of her wearing a brown sweater and jeans (an outfit she’s often seen in) as she irons slacks at an ironing board. In contrast, the bookshelves are serious: Nehru, Mary Baker Eddy, Unsung Champions of Women, Governing America, The Hite Report on Male Sexuality, Men Who Rape and Servan-Schreiber’s The Power to Inform. Nearby are two awards: the 1983 Spirit of Achievement Award presented to her by the New York Chapter of the National Woman’s Division of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine at Yeshiva University for her pioneering courage as a political activist and writer on behalf of women’s rights, and the Woman’s Way Fifth Annual Lucretia Mott Award.

But probably the most revealing item one could find would be her book, Outrageous Acts. In its introduction, Steinem discusses how she became driven to want the rightful, equal credit of a first-class citizen. Other chapters include “The Real Linda Lovelace,” strong medicine for anyone with romantic notions about the Lovelace lifestyle, and “Ruth’s Song (Because She Could Not Sing It),” which portrays Gloria’s late mother as a helpless mental patient for most of her adult life. Steinem’s father had deserted the family and Steinem essentially spent her childhood and teen years as caretaker for her mother, living on the edge of poverty. The last essay in the book, “Far From the Opposite Shore,” discusses the responsibility she now feels to help all women.

PLAYGIRL: I have the impression, from reading your book, that you have a tremendous maternal instinct toward women. Is that true?

STEINEM: It’s not maternal. What really happened was that feminism made sense of my life. And it also helped me as a writer. Up to then, I’d been imitative, trying to write like the grownups, like male writers. I hadn’t used my own experience. I had been led to believe that women’s experiences were irrelevant or unusable. And the understanding that the sexual caste system, or whatever you want to call it, is not decreed by God, biology or Freud and can be changed, helped me so much. I can’t fail to explain how it helped me, and to report on women who are changing. I think I feel more like a sister than a mother.

PLAYGIRL: What occupies most of your time nowadays?

STEINEM: The magazine—as an umbrella. But under that umbrella fall many different kinds of activities: fundraising, selling advertising, editorial content, public speaking, going on television. We’ve never had enough money to publicize the magazine and have always done it free.

PLAYGIRL: Do you have enough money personally?

STEINEM: I have enough for now. I’m certainly not saving anything for the future. I think that sometimes the busier and happier you are, the less time you have to spend money, anyway. I notice that I don’t like to shop anymore, and I used to. And I think, in a way, when women don’t have power in the world, which most of us don’t, we get focused on two other kinds of power: shopping and getting men to fall in love with us. Both of those kind of fall away as you get happier with your work.

PLAYGIRL: The impression you’ve given is that you’ve always been too busy to go shopping.

STEINEM: Oh, no. I’ve always been a great time-waster—even now, I’m very good at it. By wasting time I mean going home and watching two old movies on television instead of going to sleep like I should because I have to get up early for some appointment. Nobody ever accused me of being efficient, but I have a lot of endurance. I’m a character type: I’m good in emergencies, but I’m terrible in everyday life. If there’s a real emergency, like someone who’s choking in a restaurant or there’s a deadline here at the magazine, I’m good at that. But I can’t pick up my laundry; I can’t get my apartment organized.

PLAYGIRL: You used to have a studio apartment years ago, with a platform bed.

STEINEM: I still live in the same place—since about 1968 [on New York’s Upper East Side]. At the low point of the real-estate market in New York, buildings on my block were available, and so five of us bought our building for $160,000. Now we just have to pay maintenance. If it weren’t for that, we would have all had to move by now, because the rents have gone up tremendously. I have two big rooms— a living room and a bedroom—on one floor. I use the bedroom as an office, so I have the bed on a high balcony in the living room. The kitchen is a converted closet. I shared a one-room studio with another woman for years before I moved there.

PLAYGIRL: What’s your assessment of the current abortion backlash?

STEINEM: It is very frightening and very dangerous that Reagan and the right wing are opposed to reproductive freedom. That is, they are opposed at every level to women’s ability to decide whether and when to have children.

The bottom line of patriarchy is the need for individual men, or the family, the state, the church, whatever, to control women’s bodies and determine how many children a woman should have, what race should be encouraged to have more, and who owns those children. So I think that abortion is the most obvious front line of the battle for reproductive freedom. But it’s not the only part of it.

We are also struggling to get safe conditions for women who wish to have children— safe contraception and freedom from sterilization. All of those issues are part of reproductive freedom. The problem is that since this abortion issue is the bottom line of power for a patriarchy, whether it’s a capitalist or a socialist one, it’s the area of most resistance. And if women can decide whether and when to have children, then we take a major power away from the state: the power to decide how many workers they need, how many soldiers, and so on.

So [abortion] has always been the one issue on which legislators would vote against their own financial interest. They know that as right-wing legislators, if they deprive poor women of Medicaid-funded abortions, as they have, it’s going to cost many, many times more money to support the woman and support the child. But there’s a form of control that’s more important than economics. That’s the hallmark of every patriarchy, which is an authoritarian exercise of extreme controls…

… Keep reading on PLAYGIRL+